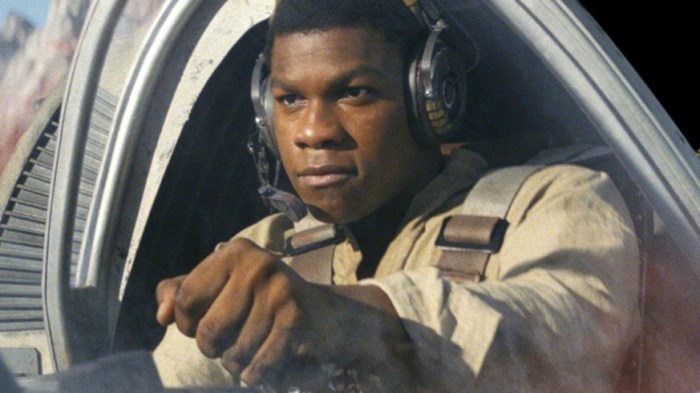

If you’re a serious actor, you do what John Boyega has done: You make a “Star Wars” movie, then you star in a dark and gritty drama that speaks to real-world ills. That said, when the young “Force Awakens” actor, 25, found himself on “Detroit” — Kathryn Bigelow’s account of the 1967 Detroit riot, which lasted five days and saw the racially-torn city turned into a war zone, complete with the National Guard stomping around — he saw that not everything was different.

“It seemed small until I saw tanks rolling through the street,” Boyega says with a laugh.

The riot, which Boyega prefers to call a “rebellion,” began when relations between the low-income black populace and the mostly white (and very aggressive) police force came to loggerheads. The bulk of “Detroit” zeroes in on one episode: when, on day three, white cops went to investigate a possible (and, as it were, erroneous) shooting at the run-down Algiers Motel. They rounded up 12 suspects — 10 black, two white — and physically and mentally tortured them. When they left, they’d killed three innocent people.

Boyega plays Melvin Dissmukes, a security guard who found himself tagging along with the police. At first he tried to help, thinking the presence of a black authority figure would mollify the cops’ rage. He was wrong.

“Dissmukes really embodies the complexities of this story,” Boyega says. “He didn’t belong to any particular side. He was caught in the middle of it. He was trying as much as possible to balance everything out. That’s a hard role to play as one man involved in such a situation.”

The cops were acquitted of all charges — far from the only chillingly thing it has in common with today’s headlines. Dissmukes, whom Boyega spoke with during filming, was seen by some members of the black community as being in league with the officers.

“He told me about being called an ‘Uncle Tom’ because he was involved in the situation,” Boyega says. “People said, ‘Why didn’t you do more? Why didn’t you stand up for yourself?’ It’s very, very easy, when you’re looking at the Rebellion from the outside-in, to say that. We’d all want to be the superhero in that situation. That’s now how life goes. Everybody has something to say until it goes down. It was a very scary situation, and he tried his best.”

For Boyega, “Detroit” speaks to the way relationships between law enforcement and civilians can become frayed.

“These officers, who were not held accountable, didn’t take their responsibility seriously, which is to protect and to serve. The key word is ‘serve.’ You’re part of a service, and it’s supposed to come from the good side of humanity, to represent something positive. Unfortunately, that was twisted,” Boyega explains. “It almost feels like a situation in which someone wears a mask to portray one thing and then is something completely different underneath. I’d rather you just come in a villain costume, so I know who you are.”

Boyega grew up in the Peckham district of South London. He never had the kind of fraught relationship with cops, not the way you see in “Detroit” or in parts of America.

“It doesn’t feel like I’ve been targeted in any way. So my perspective is very different,” Boyega says. Still, he has come of age during the 2011 London riot. “That was based on the same kind of social unrest people felt back then. It’s interesting to see that in this film — to show that when the balance between civilians and law enforcement is not completely clear, you can make people feel very tense. That’s the kind of world Dissmukes was living in.”

For Boyega, “Detroit” isn’t only about Detroit in 1967, or about America right now.

“The slogan to ‘Detroit’ is ‘It’s time we knew.’ For me, that reflects on the many other stories people don’t know about,” explains Boyega. “It’s important to understand that all over the world, race relations is an issue — even in places you wouldn’t expect that to happen. In India, it’s an issue. Same with Brazil. It’s interesting to see how that hasn’t gone away. And it’s been so long since it happened.”

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge