By Jonathan Stempel

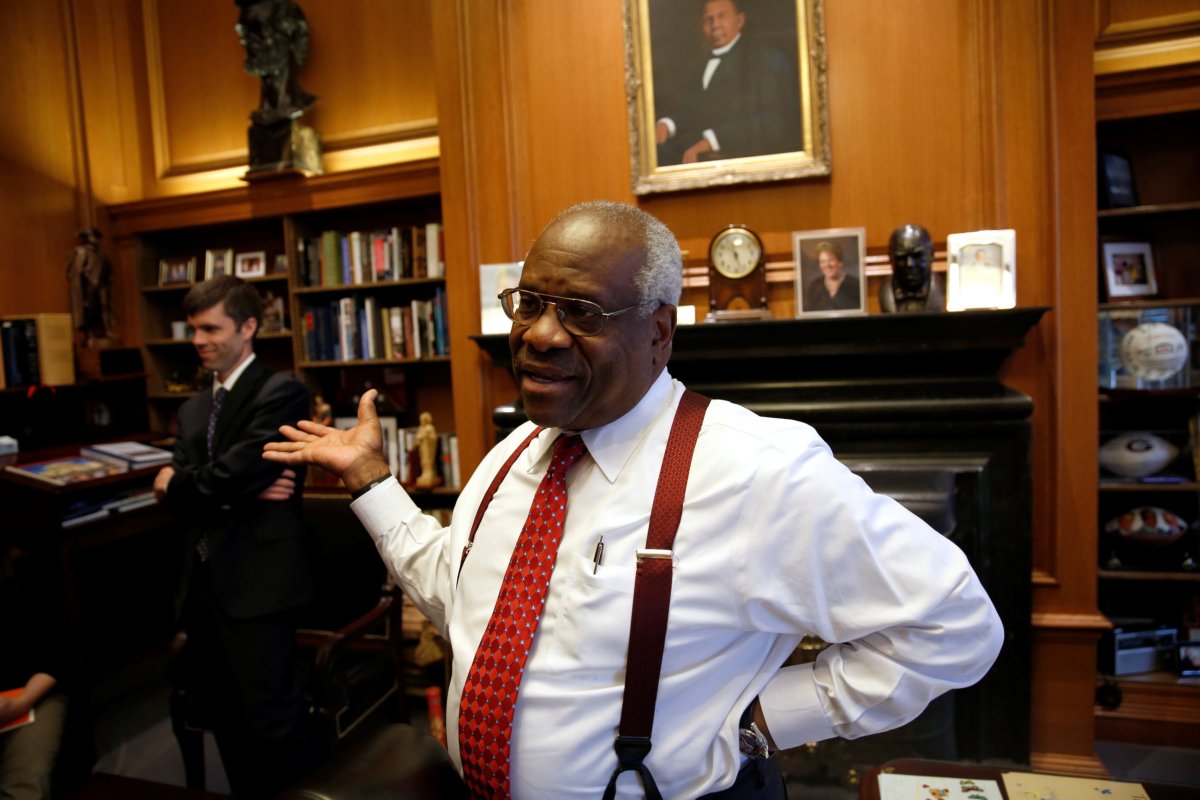

(Reuters) – Justice Clarence Thomas on Monday urged the U.S. Supreme Court to feel less bound to upholding precedent, advancing a view that if adopted by enough of his fellow justices could result in more past decisions being overruled, perhaps including the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion nationwide.

Writing in a gun possession case over whether the federal government and states can prosecute someone separately for the same crime, Thomas said the court should reconsider its standard for reviewing precedents.

Thomas said the nine justices should not uphold precedents that are “demonstrably erroneous,” regardless of whether other factors supported letting them stand.

“When faced with a demonstrably erroneous precedent, my rule is simple: We should not follow it,” wrote Thomas, who has long expressed a greater willingness than his colleagues to overrule precedents.

In a concurring opinion, which no other justice joined, Thomas referred to the court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed Roe and said states cannot place an undue burden on the constitutional right to an abortion recognized in the Roe decision. Thomas, a member of the court at the time, dissented from the Casey ruling.

Thomas, 70, joined the court in 1991 as an appointee of Republican President George H.W. Bush. Thomas is its longest-serving current justice.

The court now has a 5-4 conservative majority, and Thomas is among its most conservative justices.

He demonstrated his willingness to abandon precedent in February when he wrote that the court should reconsider its landmark 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan ruling that made it harder for public officials to win libel lawsuits.

“Thomas says legal questions have objectively correct answers, and judges should find them regardless of whether their colleagues or predecessors found different answers,” said Jonathan Entin, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “Everyone is concerned about this because they’re thinking about Roe v. Wade.”

COURT DIVISIONS

The Thomas opinion focused on “stare decisis,” a Latin term referring to the legal principle that U.S. courts should not overturn precedents without a special reason.

While stare decisis (pronounced STAR-ay deh-SY-sis) has no formal parameters, justices deciding whether to uphold precedents often look at such factors as whether they work, enhance stability in the law, are part of the national fabric or promote reliance interests, such as in contract cases.

In 2000, conservative then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist left intact the landmark 1966 Miranda v. Arizona ruling, which required police to advise people in custody of their rights, including the rights to remain silent and have a lawyer.

Writing for a 7-2 majority, Rehnquist wrote that regardless of concerns about Miranda’s reasoning, “the principles of stare decisis weigh heavily against overruling it now.” Thomas joined Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent from that decision. But even Scalia, a conservative who died in 2016, had a different view of stare decisis.

In a widely quoted comment, Scalia once told a Thomas biographer, Ken Foskett, that Thomas “doesn’t believe in stare decisis, period,” and that “if a constitutional line of authority is wrong, he would say let’s get it right. I wouldn’t do that.”

Stare decisis has also split the current court, including last month when in a 5-4 decision written by Thomas the justices overruled a 1979 precedent that had allowed states to be sued by private parties in courts of other states.

Justice Stephen Breyer, a member of the court’s liberal wing, dissented, faulting the majority for overruling “a well-reasoned decision that has caused no serious practical problems.” Citing the 1992 Casey ruling, Breyer said the May decision “can only cause one to wonder which cases the Court will overrule next.”

Thomas said the court should “restore” its jurisprudence relating to precedents to ensure it exercises “mere judgment” and focuses on the “correct, original meaning” of laws it interprets.

“In our constitutional structure, our rule of upholding the law’s original meaning is reason enough to correct course,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas also said demonstrably erroneous decisions should not be “elevated” over federal statutes, as well as the Constitution, merely because they are precedents.

“That’s very different from what the Court does today,” said John McGinnis, a law professor at Northwestern University in Chicago.

McGinnis said the thrust of Thomas’s opinion “makes clear that in a narrow area he will give some weight to precedent. But at the same time, he thinks cases have one right answer, and might find more cases ‘demonstrably erroneous.'”

(Reporting by Jonathan Stempel in New York; Editing by Will Dunham)