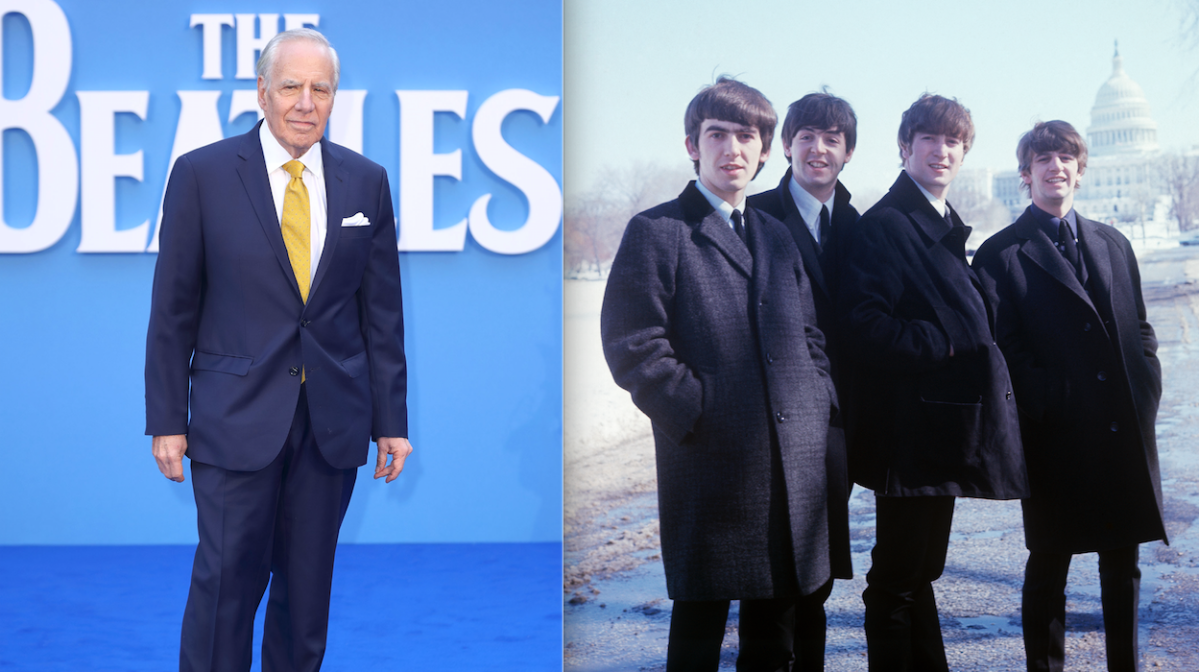

Larry Kane may not be a contender for the “fifth Beatle,” but he’s a mighty figure in Fab Four-dom all the same. The longtime reporter and news anchor — currently the host of “Voice of Reason” on Comcast out of Philadelphia —has the distinction of being the only broadcast journalist John, Paul, George and Ringo allowed to travel with them on every stop of their tours in 1964 and 1965. He stayed in touch with them afterwards, and wrote the book “When They Were Boys: The True Story of The Beatles’ Rise to the Top” in 2013.

Kane is among the most prominent talking heads in “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years,” a new documentary by Ron Howard that, true to its title, only covers the period of their hectic live schedule —a period so hectic indeed that, in 1966, they called a stop to touring so they could solely create music in the studio.

Kane talks to us about his history with them and the one song he might have helped massage into shape.

RELATED: Interview: Matt Zoller Seitz on his Oliver Stone book and talking to Edward Snowden

How did you get The Beatles to trust you?

Very easily. Most of the other reporters, the adult reporters really despised them. They would ask them questions like, “What do you eat for breakfast? Did you shower today? Do you wash your hair? Is your hair real? What kind of hemline do you like on a woman?” I basically asked them questions about what happened in the concert, about the reactions of the fans, about the war in Vietnam, about racial discrimination. I knew right away that they were intellectually curious. By asking them these questions and getting involved in a deep sense, I was able to show the world that they had tremendous intellectual curiosity. They liked that. They knew that when I chatted with them that it was going to be about philosophy. In one case I asked them if they had teenage daughters would they allow them to come to the concerts. And each of them said, “Absolutely not, it’d be too dangerous.”

It’s interesting to contrast what you see of them here —and in documentaries like the Maysles brothers’ “What’s Happening! The Beatles in the U.S.A.” —with “A Hard Day’s Night,” which is a more heightened and fictionalized version of them.

I saw that movie for the first time with them, at the Shelburne Hotel in Atlantic City. Somebody brought up a bunch of cheesesteaks and popcorn, and they had a guy come up with a big 35mm camera and showed the movie on a screen. I was able to talk to them. They were very uncomfortable looking at themselves.

“A Hard Day’s Night” also couldn’t show them smoking. In documentary and archival footage they’re constantly with cigarettes.

And drinking. They did a considerable amount of drinking in the airplanes after the shows. They never drank before the shows. They also ate very lightly. They were so busy they couldn’t even deal with a heavy meal. You see how thin they are at the time. They were really remarkable guys. Later on there was controversy in friction, in their lives and with the contracts. But in those days they were truly the Four Musketeers. Ringo leaned heavily on them. In fact, when they broke up he was probably the most affected.

I always think Ringo’s very underrated. He was a fantastic drummer, no matter what some people have said.

He had 18 years of really unhealthy behavior — rehabs and everything. But in 1989 we did a little show at my TV station with Ringo. It was really interesting to see him, because he was still recuperating. He was thinking what he could do on stage. He had some songs and he was a great drummer. But he wanted to put a show together. What a genius concept to make the All-Starr Band and give all these artists a chance. Clarence Clemons, Joe Walsh, Nils Lofgren, who was unceremoniously thrown out of the Springsteen band. All these people were brought together by Ringo for all these years. He gave them an outlet to revive their careers. While he couldn’t do what Paul does and do two-, three-hour shows, he was able to show his talent through the talents of other people. He revived a lot of careers.

This movie shows how draining and relentless their touring schedule was. You can see why they’d want to stop it entirely and retire to the studio. Did you get a sense of how they were able to earmark bits of time in the early days to actually write their songs?

I was on the plane when they were writing “Eight Days a Week.” They had a tape recorder in the back, and they were playing the beginning of the song. I told them I thought the beginning was a little too slow. Now, I know as much about music as an electrician knows about brain surgery. But that was just my opinion. If they took my advice, then it really should be Lennon-McCartney-Kane on that song.

You stayed in touch with them after they broke up, too.

In the 1960s or 1970s — or maybe into the early part of the 1980s, too — they did not know they were going to become the iconic band they are today. They just didn’t know. I had a conversation with John in 1978 and I said, “What music are you listening to these days?” And he said, “The Beatles.” He said, “I collect a lot of Beatles material, because I think they were a good band. I think our music was much better than I thought it was.” It was interesting to hear him say that. Paul and I had a long conversation last night. He said something along the lines of “We all thought we could do better.”

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge