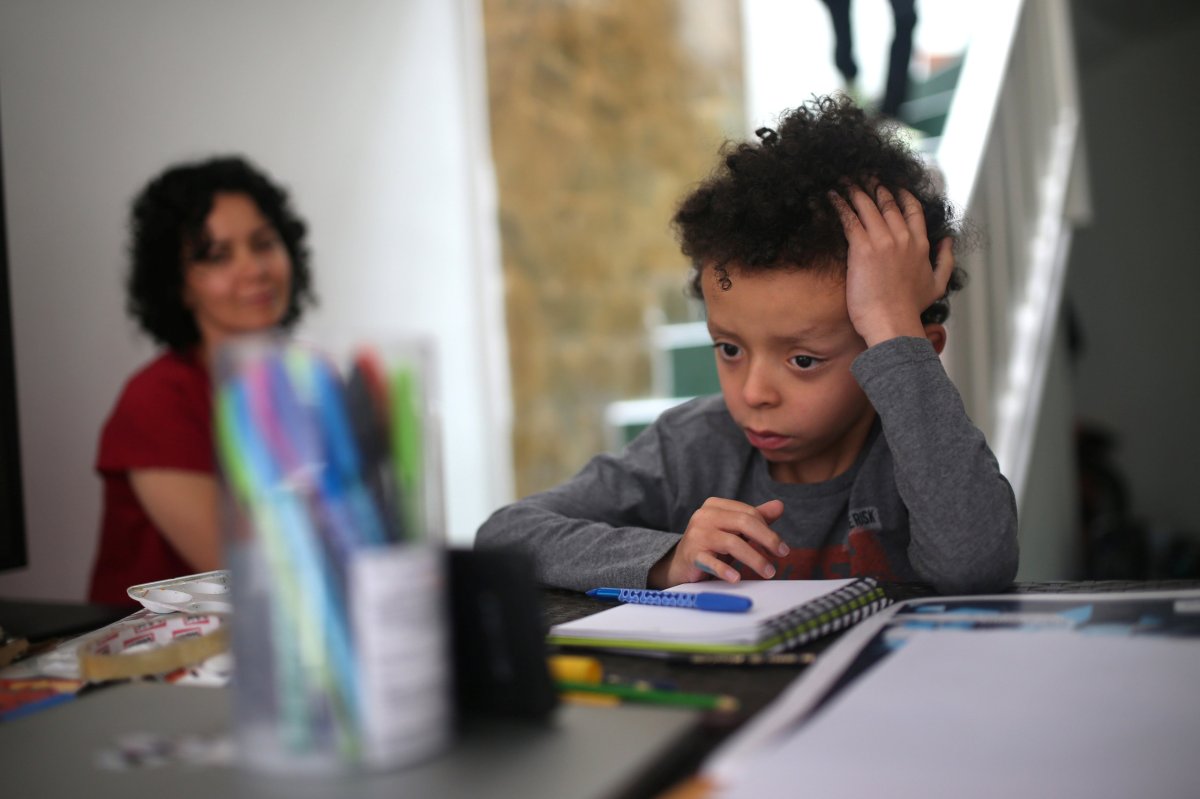

SAN CRISTOBAL, Venezuela (Reuters) – Vanesa Jaimes studied to become an administrative worker in Venezuela’s health care system, but these days she could be more accurately described as a teacher – to her four kids.

Since the country went into quarantine to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, Jaimes has spent her days juggling competing demands for internet access and monitoring homework. Helping her 8-year-old son Gabriel with math required her to re-learn long division because, like many adults, she hasn’t done it in years.

Gabriel and his siblings are joined by an estimated 95% of Latin America’s children whose school has been canceled due to the outbreak, according to the United Nations children’s agency Unicef.

That is particularly worrisome for Latin America, where educational inequalities can be stark and access to reliable internet patchy.

“I have internet that’s not very good, when it doesn’t work I use the data on my phone,” said Jaimes, 33, in a living room cramped with furniture and computers that Gabriel and his brother Mateo also use for soccer practice in the afternoons.

The school cancellations are an unprecedented interruption in education for Latin America, Unicef said this month, threatening to fuel drop-out rates and worsen inequalities between poor kids and their wealthier counterparts.

Denisse Gelber, a researcher with Chile’s Center for Educational Justice, said it was unfeasible for parents, some of whom continue doing manual jobs outside the home, to continue supporting their children’s education.

“Schools are central in most societies because they attempt to rebalance inequalities of where people come from,” she said. “Unfortunately there are some families who are at a real disadvantage.”

In Chile, where violent street protests broke out last year over long-running and deep-seated inequality, teachers, academics and actors in an open letter last week called on television stations to run educational programming to avoid worsening “gross inequality.”

Communist-run Cuba is already doing that. This week, it started dedicating two of its eight television channels to part-time teleclasses for schoolchildren from ages 5 to 18, a mechanism it has used at times since Fidel Castro’s 1959 leftist revolution.

Zebrezeit Barrera, 37, an engineer in Havana, said the teleclasses help her six-year daughter study mathematics, Spanish and nature three times a week.

“The explanation is for everyone, the kids and their families,” she said.

The reliance on internet to keep education going is also driving inequality between urban schools and their typically poorer counterparts in rural areas with less infrastructure.

Martha Gracia, who teaches information technology at a school in the small Colombian town of Arbelaez, said teachers are sending homework exercises to students by WhatsApp, even though only around 30% of them have access to the application.

The rest will have to rely on their parents collecting paper copies of the instructions from a local coordinator.

“The majority of the students are from rural areas and don’t have resources or computers at home,” said Gracia.

In the remote community of Palo Mocho in southern Venezuela, where internet and cell signal are sparse, education has returned to rudimentary roots.

Teachers post a sign at the local store asking parents to visit the school so that they can copy homework assignments written out on a sheet of paper taped to a chain-link fence.

“It’s not easy to keep classes going,” said Ariannys Rengel, 32, a school director who has been visiting local families, at times walking up to an hour to reach their homes.

“The government talks about technological advances, but out here there’s no television, no radio, and no smartphones.”

(Additional reporting by Aislinn Laing in Santiago, Oliver Griffin in Bogota, Nelson Acosta in Havana, and Maria de los Angeles Ramirez in Palo Mocho, writing by Brian Ellsworth; Editing by Rosalba O’Brien)