BEIRUT/JERUSALEM (Reuters) – Lebanon and Israel, formally still at war after decades of conflict, launch talks on Wednesday to address a long-running dispute over their maritime border running through potentially gas-rich Mediterranean waters.

The U.S.-mediated talks follow three years of diplomacy by Washington and were announced weeks after it stepped up pressure on allies of Lebanon’s Iran-backed Hezbollah.

They also come after the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain agreed to establish full relations with Israel, under U.S.-brokered deals which realign some of Washington’s closest Middle East allies against Iran.

Hezbollah, which last fought a war with Israel in 2006, says the talks are not a sign of peace-making with its long-time enemy. Israel’s energy minister also said expectations should be realistic.

“We are not talking about negotiations for peace and normalization, rather an attempt to solve a technical, economic dispute that for 10 years has delayed the development of offshore natural resources,” minister Yuval Steinitz tweeted.

Still, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has described the decision to go ahead with the talks as historic, and said Washington looked forward to separate talks later over disagreements on the land border.

Wednesday’s meeting will be hosted by the United Nations peacekeeping force UNIFIL, which has monitored the land boundary since Israel’s withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000, ending a 22-year occupation.

A Lebanese security source says the two sides will meet in the same room in UNIFIL’s base in south Lebanon, but will direct their talks through a mediator.

LEBANON CRISIS

Disagreement over the sea border had discouraged oil and gas exploration near the disputed line.

That may be a minor irritation for Israel, which already pumps gas from huge offshore fields. For Lebanon, yet to find commercial reserves in its own waters, the issue is more pressing.

Lebanon is desperate for cash from foreign donors as it faces the worst economic crisis since its 1975-1990 civil war. The financial meltdown has been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic and by an explosion that wrecked a swathe of Beirut in August, killing nearly 200 people.

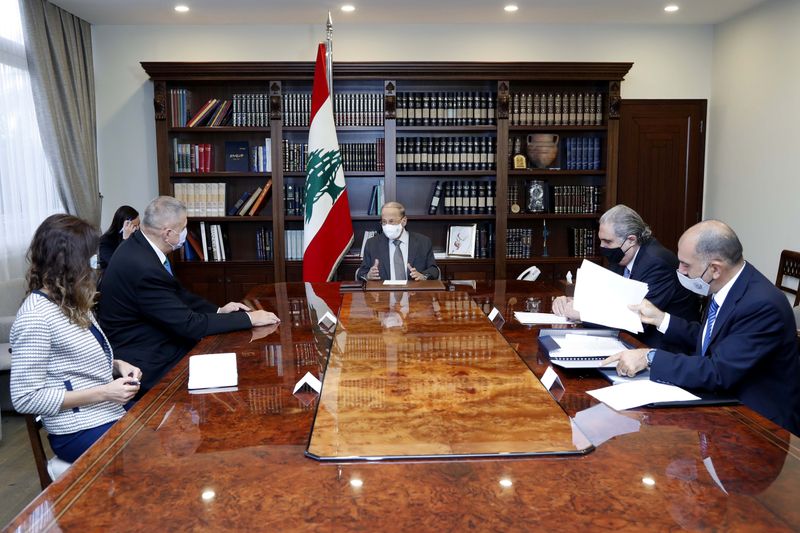

Struggling to form a new government to tackle the multiple crises, some Lebanese politicians even argued this week over the formation of their negotiating team, with the prime minister’s office complaining it was not consulted by the presidency.

“The Lebanese negotiator will be much fiercer than you can imagine because we have nothing to lose,” caretaker Foreign Minister Charbel Wehbe said.

Hezbollah’s political ally, the Amal party, has also come under pressure. Last month the United States sanctioned Amal leader Nabih Berri’s top aide for corruption and financially enabling Hezbollah, which it deems a terrorist organisation.

David Schenker, the U.S. assistant secretary for Near Eastern affairs, who landed in Beirut on Tuesday, has said more sanctions remained in play.

For Hezbollah and Amal, the decision to start the border talks is a “tactical decision to neutralize the tensions and the prospect of sanctions ahead of the U.S. elections,” said Mohanad Hage Ali, a fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center.

Berri, a Shi’ite leader who led the border file, has denied being pushed into the talks.

In 2018 Beirut licensed a group of Italy’s Eni, France’s Total and Russia’s Novatek to carry out long-delayed offshore energy exploration in two blocks. One of them contains disputed waters.

(Reporting by Ellen Francis and Dominic Evans in Beirut, and Ari Rabinovitch in Jerusalem, Editing by William Maclean and Gareth Jones)