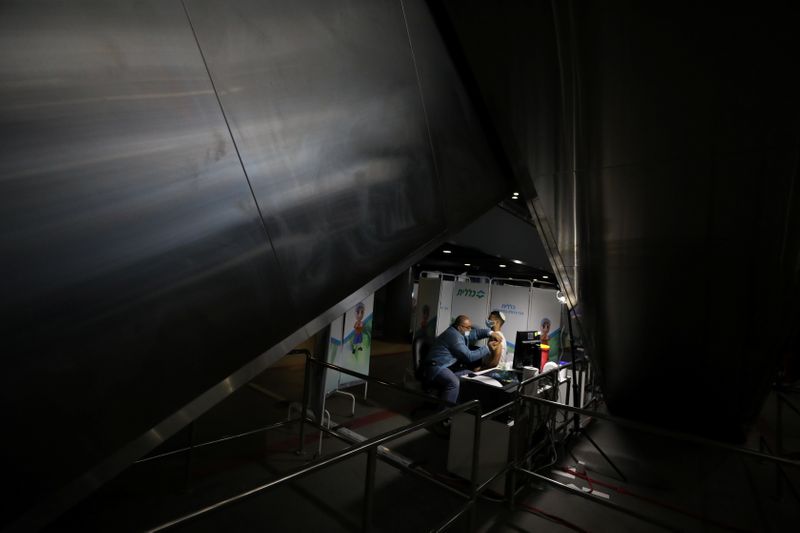

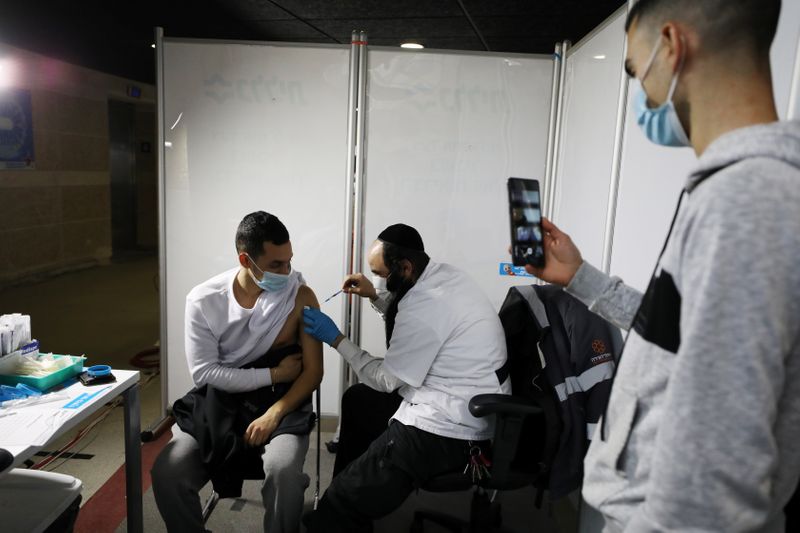

TEL AVIV (Reuters) – Israel has led the world in COVID-19 vaccinations. Now it faces another challenge that other countries will have to grapple with: how to balance public health and the rights of the unvaccinated.

Its decisions will affect every walk of life – from schools to work, and culture to worship.

Half of Israelis have received their first shot, and the country began reopening its economy this week after a year of lockdowns and remote working.

But several activities have been deemed off-limits to the unvaccinated, angering those who cannot get the jab for health reasons, or refuse it as a matter of principle.

Some employers already plan to ban unvaccinated workers from the office, which rights groups fear could cost them their jobs. Unions have suggested workarounds, such as COVID-19 tests every 72 hours.

“I’m already at peace with the fact that I won’t be invited to certain events or allowed into areas of entertainment,” said Hila Bar, a business owner who is sceptical of medical science and does not plan to get vaccinated.

“So I won’t go,” she said. “And I won’t patronise certain businesses either – not because I don’t want to, but they do not want my business.”

Israel, where the vaccine rollout is fast but not mandatory, is a world leader in inoculations. Other countries are likely to scrutinise its early experience to see how it addresses mostly unanswered questions about balancing individual rights with obligations to public health.

“Whoever does not get vaccinated will be left behind,” Health Minister Yuli Edelstein warned in recent weeks.

Edelstein has made clear that newly introduced perks for the vaccinated – including access to theatres, gyms, and resort areas along the Dead Sea – are incentives to get inoculated.

But some advocates and employers are concerned that parliament has not passed any new laws regulating workers’ return to offices or offering protections for the unvaccinated, saying it will force employers to devise their own rules.

Early discussions around guidelines and legislation point to employers, authorities and courts putting public health concerns before individuals’ demands.

Intel’s Mobileye unit, in Jerusalem, says unvaccinated workers will not be allowed to come to the office as of April 4, but can work from home if their assignment allows.

The company estimates around 10% of its 1,500 employees will not get vaccinated. If they must come to the office, they will need to provide a negative PCR test taken within the prior 48 hours.

“It is our responsibility to make our offices a safe place – the greater good of our employees and their families trumps any other consideration,” Chief Executive Amnon Shashua wrote to employees in an email seen by Reuters.

CIVIL RIGHTS

A landmark study released on Wednesday showed the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine being used in Israel cut symptomatic cases among Israeli recipients by 94%.

But some officials privately estimate that 10% of Israelis over 16 – around 650,000 people – do not intend to get vaccinated.

Even asking employees to share their vaccine status could violate medical privacy rights, some advocates say, with potential ramifications for civil liberties that may eventually be challenged in Israeli courts.

“The question is how do we reopen the market, the economy, and life, without harming people that cannot or would not get vaccinated,” said Sharon Abraham-Weiss, executive director of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI).

“It’s the vulnerable people, those that are not unionised, or temp (workers) or others who would bear the burden,” she said, while calling for legislation.

Business leaders have also called for new laws. The health ministry did not comment when asked if legislation offering job protection to the unvaccinated was being drawn up.

Some large trade groups have begun drafting policy guidelines for members, including the Manufacturers Association of Israel, which represents 1,800 companies employing almost half a million workers.

The group’s members are “not chasing people in the street to stick some syringes in their shoulders and force them to vaccinate,” though they are doing everything they can to encourage it, the group’s president, Ron Tomer, said.

But according to a legal opinion commissioned by the group and reviewed by Reuters, members may ask employees if they were vaccinated as a “safety measure” to prevent infecting others rather than as a request for personal medical information.

Employers should take reasonable steps to allow unvaccinated staff to work from home or in separate bubbles, but those who cannot do so can be sent on unpaid leave, or, as a last resort, fired, the opinion says.

“If you don’t want to take the injection, it’s OK … the employee (has a right) to protect his privacy. But on the other side there are rights of the public, the employers, the clients – the people that we give services (to),” the opinion’s author, prominent employment attorney Nachum Feinberg, told Reuters.

Offering a potential workaround, Israel’s largest labour union, Histadrut, suggested that unvaccinated workers who cannot work at home present negative coronavirus tests to their employers every 72 hours.

‘MATTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH’

Israel on Sunday launched a “Green Pass” system granting certain privileges to citizens who have had both doses of the vaccine or have recovered from COVID-19.

In one of its first real-life applications, only those carrying a government-validated certificate were allowed to attend a small open-air concert in Tel Aviv this week.

And parliament on Wednesday passed a law allowing the health ministry to give municipalities the names of residents who have not had a shot.

ACRI has opposed the legislation, arguing it violates privacy rights.

The law faculty at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem argued in a position paper that regulating vaccination “is a matter of public health, and not a private medical issue”.

Existing Israeli laws grant the health ministry the legal authority to impose restrictions on the unvaccinated, and even to obligate vaccination in certain cases, the position paper says.

“Those who fulfil their obligation to vaccinate should not be asked to bear the cost of others choosing not to,” said David Enoch, a professor in the philosophy of law at Hebrew University.

(Reporting by Rami Ayyub and Steven Scheer; Editing by Mike Collett-White)