CHICAGO (Reuters) – Pamela Pickens swayed her hips as her husband Tom led her in an impromptu dance to the strumming of guitarist Studebaker John at Chicago’s famed blues bar, Kingston Mines.

The couple, wearing fedora hats and wide smiles, had driven five hours from their home in southeast Indiana to visit their favorite blues club, which had recently reopened for live performances after a year of shutdown due to COVID-19.

“It’s so great to be back,” said Pickens, 66, taking a drag from a cigarette outside the venue on a dancing break. “It makes me feel alive.”

Inside the bar in the city’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, a diverse crowd filled long tables, where they threw back cold beer and baskets of fried food while bopping along to the music.

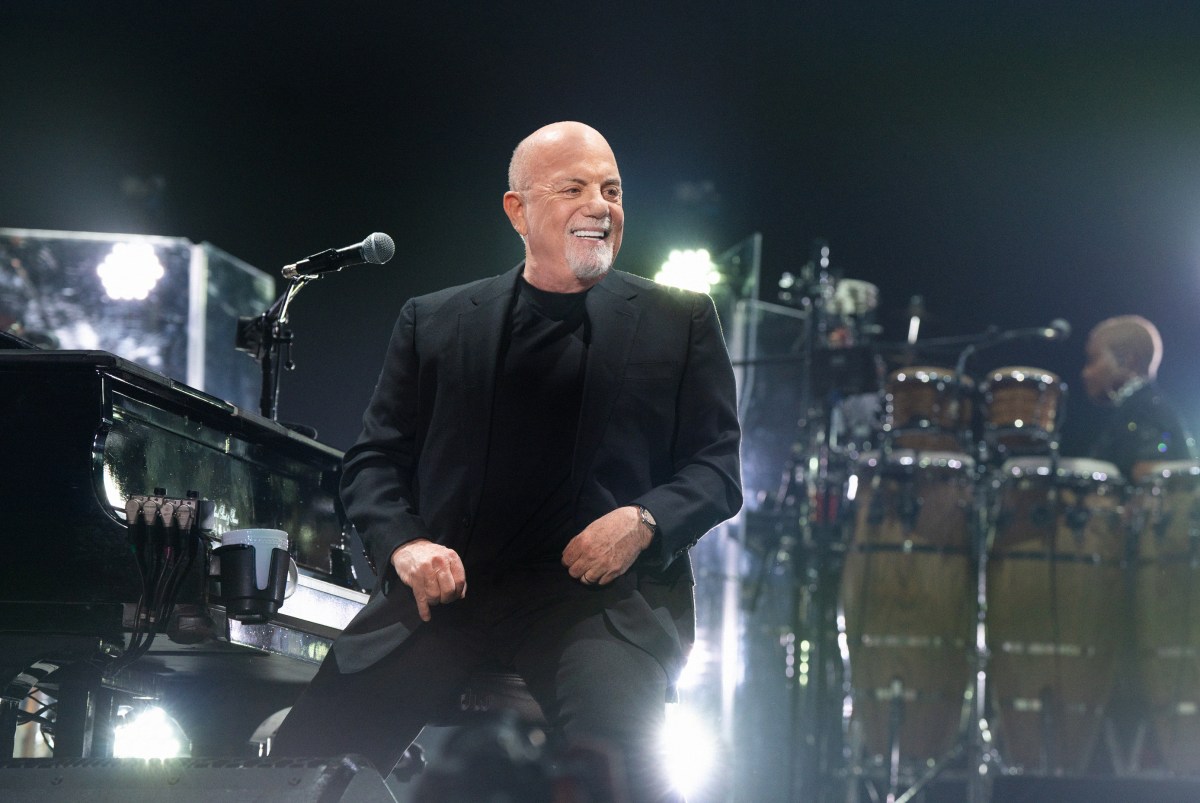

At concert venues across the United States, from Denver to Washington, D.C., similar scenes have played out in recent weeks as cities lift COVID-19 restrictions and newly vaccinated music lovers return to their old haunts for the thrill of live music in public company. It is one of the unmistakable sights – and sounds – of American life returning to normal, or closer to it.

Venues large and small are seeing demand soar for performers of all genres, who are scrambling to fine-tune their acts after a year of inaction.

“When we started playing again, it was an out-of-body experience,” said blues guitarist Joanna Connor, gearing up for her show at Kingston Mines one June evening. “It’s reaffirmed that I need to do this for my soul.”

In interviews, concert lovers described the invigorating experience of hearing live music in a crowded room once again. It felt like the antithesis of the homebound isolation they endured over the past year, and for many, it felt like an antidote.

In Alexandria, Virginia, a mostly middle-aged, Black crowd of more than 200 people swayed their arms in time with a wailing trombone at the Birchmere Music Hall’s tribute to Motown concert. It was the first of many summer concerts that Lynette Shingler and her husband Earl planned to attend, now that they were vaccinated against COVID-19.

“If you are a music fanatic, listening to it on the radio is not the same,” said Shingler, a 52-year-old federal employee in a floor-length blue dress. “You’ve really got to be in the atmosphere.”

Across the river in Washington, D.C., a younger crowd of thousands has packed the dance floor night after night at Echostage, a nightclub that reopened its doors on June 11.

Lit up by neon strobe lights and the glow of thousands of iPhones in outstretched hands, the room shook with bass vibrations as French DJ David Guetta jumped up and down onstage.

Guetta is one of several top electric dance music (EDM) headliners that Echostage has welcomed over the last month. The 3,000-person capacity venue started offering tickets for their summer lineup in May, selling 20,000 tickets in just the first few days, far outpacing their pre-pandemic sales rate, Vice President of Operations Matt Cronin said.

“I attribute it to just an absolute hunger for people to get out and see music again,” he added.

In Denver, New Age guitarist Victor Towle has already played more than twice as many gigs as he did in 2020 since local bars restarted live entertainment in May.

Towle spent the last year recording a solo instrumental album since he could not play live. His return to the stage and to his typical three-hour performances has felt abrupt but “exhilarating,” he said.

“I’m noticing that I’m out of shape, you know. I’ve got to get my voice and my chops back,” he said.

‘HEE HAW HEAVEN’

In Decatur, Georgia, in late June, Danica Hart stood onstage before dozens of people in Eddie’s Attic, a small venue for up-and-coming Country and Americana bands, wearing a baseball cap and jeans.

“Hello Decatur!” she cried out to the cheering crowd. “Let’s make some real noise!”

Hart, who leads the trio Chapel Hart, said the group was accustomed to scraping by since they got their start busking in New Orleans. But the pandemic year had pushed them to their limits. “At times we were lucky to have gas money,” Hart said.

“Now we’re back,” she said. “It feels like a rebirth. People are ready to come out for real, live music. They’ve missed this and we’ve missed the people… We’re in hee haw heaven.”

Like many venues that were shuttered, Eddie’s Attic is still ramping up operations. It has reopened with limited capacity, and the kitchen remains closed. Still, co-owner Dave Mattingly said it is a big improvement from the heartbreak of watching dust accumulate on tables and chairs for a year.

“To go from that to hearing this music, the people stamping feet and clapping along, it’s like lightning striking,” Mattingly said.

As Chapel Hart jammed out to their twangy numbers with names like “Jesus and Alcohol,” concertgoers reflected on what it was like to miss live music for a year, and then experience it again.

“It’s like starving, slowly,” 54-year-old Sherry Mills, a local middle school music teacher, said of her inability to see live bands.

“I feel liberated,” said Barry Rosner, 76, a big grin on his face and his arms stretched wide as he stood just outside the venue.

Rosner, who said it was his first show in more than a year, was lingering to catch a word with the members of Chapel Hart. “I want to tell them thank you and we’re not afraid to go out anymore.”

(Reporting by Brendan O’Brien in Chicago, Rich McKay in Decatur, Georgia, Andy Hay in Taos, New Mexico and Gabriella Borter in Washington; Writing by Gabriella Borter; Editing by Paul Thomasch and Lisa Shumaker)