WASHINGTON (Reuters) – As the clock ticks toward the U.S. presidential election in November, state election officials are devoting more time – and money – to educating voters about the dangers of disinformation while reassuring them that the system is fundamentally sound.

On a recent Zoom call, Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, the state’s top election official, ran through slides showing altered Facebook photographs, misleading tweets from the last presidential election and photographs of Russian hackers.

“Disinformation spreads like a virus,” the presentation warned its audience of Black pastors, minority leaders, and civil rights campaigners, detailing how Moscow carried out “an all-out assault on African-American voters using social media.”

It was an eye-opener, one attendee said.

“We had not had this kind of training or dialogue that I know of in the 20 years that I have been in Ohio,” said Andre Washington, who leads the state chapter of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an African-American trade union organization.

LaRose’s sessions are one in a series of initiatives being rolled out by the state and other local officials who run elections across the country to help head off a repeat of 2016, when hackers and trolls pumped stolen emails and propaganda into U.S. public forums. It remains unclear if – or how – it affected the outcome of the vote.

Senior intelligence officials predict that Russia – along with China and Iran – will attempt to influence the 2020 election as well.

The process this year will be even more fraught due to the coronavirus pandemic, which will compel many Americans to use unfamiliar new forms of voting, including drive-throughs, drop-off boxes, or mail-in ballots.

Partisan politics is also poisoning the discourse. Trailing in opinion polls, Republican President Donald Trump has said mail-in ballots will open the door to massive fraud, despite the lack of evidence for such a view.

“When we were thinking about this 10 months ago or two years ago, we were probably thinking more in terms of external, foreign adversaries – Russia doing misinformation campaigns,” Kim Wyman, Washington’s secretary of state, told Reuters in June.

Referring to a tweet that Trump had posted that day alleging that millions of mail-in ballots would be printed by foreign countries in a “RIGGED 2020 ELECTION,” she said: “Today’s tweets show that it can come from anywhere.”

On Thursday, Trump went a step further and raised the possibility of a delay, which is not in his power to do. “2020 will be the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history … Delay the election until people can properly, securely and safely vote???,” he said in a tweet.[L2N2F111T]

Surveys suggest Americans were already worried about the integrity of U.S. elections before the coronavirus. A Gallup poll conducted in 2019 said 59 percent of Americans are “not confident” in the honesty of U.S. elections. And a Marist Poll from January said those polled believed “misleading information” represented the biggest threat facing the vote.

Wyman said that her mission – and the mission of “every election official in this country right now” – was “getting people to have confidence in our system.”

U.S. political parties, donors, and social media platforms are all trying to be on better guard than they were in 2016.

Over the last four years, social media giants, including Facebook and Twitter, have improved their ability to spot inauthentic behavior, like Russia’s past use of “sock puppet accounts” to spread fake or inflammatory claims. Election officials say they now have direct lines of communication to platforms like Facebook, allowing them to fast-track the removal of election-related lies.

LaRose of Ohio, who like Wyman is a Republican, said he is trying to fight disinformation no matter what the source.

“It can be uncomfortable when it’s a member of my party that shares something that’s incorrect, but – my God – I wear the referee’s jersey in this capacity,” LaRose told Reuters.

NEW TACTICS

Wyman and LaRose are part of a cadre of election officials who are trying new tactics to inoculate voters against false claims.

That includes developing and expanding local government social media accounts to counter misinformation, hiring advertising firms to design communications strategies, and offering pre-recorded virtual tours of voting facilities, educational television broadcasts and election classes for local journalists.

Public outreach in past years tended to feature generic get-out-the-vote literature; this year’s ads are aimed at reassuring constituents that their vote will be properly tallied.

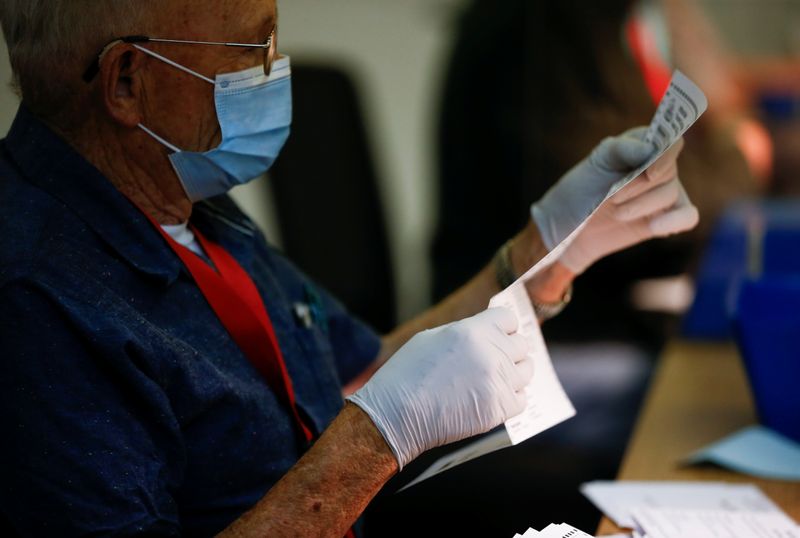

In Washington’s Thurston County, home to the state capital, Olympia, auditor Mary Hall said authorities were wiring up the county ballot processing center – a converted warehouse southwest of town – to livestream the vote-counting process.

“Every part of our Ballot Processing Center is recorded during the election,” read one recent Facebook ad. “These recordings are kept for months after certification so we can keep a record of everyone that had touched a ballot.”

There’s no nationwide tally on how much money is going to the effort. Election observers say while budgets remain small, they’re seeing a spending surge this year compared to past cycles.

Hall said Thurston County officials used to spend around $500 for Facebook ads to communicate with voters. This year the county was putting $35,000 toward ads on Facebook, music streaming service Pandora, cable television, and in the local newspaper.

Iowa will “easily spend” twice as much as in 2018, Secretary of State Paul Pate told Reuters, without giving details.

Election security experts who spoke to Reuters said while they support the educational effort, it would likely only reach a small percentage of the population before November.

All the more reason to get ahead of the problem, according to a senior official at the Department of Homeland Security, who spoke to Reuters on condition that he not be named.

“We believe it’s important to control the battle space now,” he said.

(Reporting by Christopher Bing and Raphael Satter; Editing by Chris Sanders and Sonya Hepinstall)