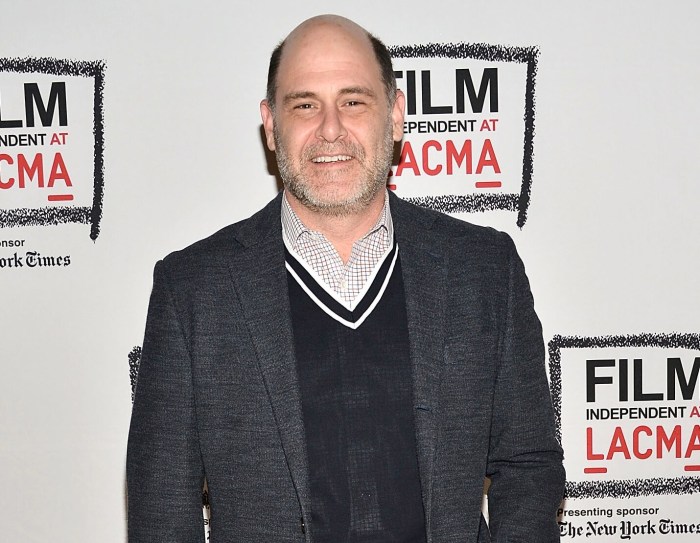

Matthew Weiner understands the emphasis that’s been placed on the final episodes of “Mad Men,” but at the same time he thinks that way of looking at them might detract from the experience. Or, to put it more bluntly: “I think there’s too much weight put on the ending of a TV show. ‘Dear America: Shut the f— up and watch,'” Weiner offers with a laugh. “That’s my headline.” Well, he is the boss — for today at least. THE ART OF THE ENDING

From a show-running perspective, when you knew how much story was left, did you already know how it was going to end?

No. Well, I knew where I wanted it to go when I sold the show, believe it or not, but I didn’t know how it would happen. And how it happens is everything on that show. But I have to say, the security of knowing that you have three more seasons to go without anymore fear of cancelation is an incredibly gratifying vote of confidence. On the other, it was completely terrifying because I didn’t really want to change what I was doing. So we still treated every season like it was the last season of the show. There’s nothing that we were saving. There was a finale concept, which I didn’t share with the writers until probably the beginning of the last season. My wife knew about it and Jon Hamm knew about it, but that’s it. It wasn’t part of the original pitch to AMC?

No, no, no. No. And I don’t know if they would’ve remembered it. It wasn’t the same people I pitched it to. But no, it wasn’t part of it.

You knew a few years ago exactly how long you had until the end of the show.

Yeah. In between Seasons 4 and 5, it was settled that there would be three more seasons of the show, and then I found out about them splitting the last two seasons about a year later — long before the public did — and that’s where I asked for the extra episode, because I was like, “I can’t do a six-episode arc. It’s too short.” I also thought they were going to split it up in the same year. I didn’t know that they would actually be 10 months apart. The splitting up seasons has been a bone of contention for some.

I’ve had lots of different criticism of them at different points in my career or had a sometimes contentious relationship with Lionsgate and AMC, but the fact remains that I do not question their programming choices. I can’t, actually. My job is to bring the show in on budget, and if they want to take these last seven episodes and show them one a year for the next seven years, I can’t do anything about it. And quite frankly for AMC, who are the people who made that decision, this strategy is very important to them. Not only was it a huge success for “Breaking Bad,” but they’ve basically been able to stretch these properties out and checkerboard them — with “The Walking Dead” and so forth — at eight-episode clips. And you know, “Downton Abbey” is eight episodes, “True Detective” was eight episodes. These are not ridiculous quotients. It’s just there was something luxurious about having a nice 13-hour chunk for “Mad Men,” and I did construct this last season that way no matter what, even though it’s broken up. I’ve been re-watching the show from the beginning in preparation for these finale episodes.

That’s great, but just know that we built the show one episode at a time and one season at a time. We tried to paint ourselves into as many corners as we could every year. And I’m not being facetious, the end of Season 5 was the only time that I knew I would need something for the next season. So when you have something like having Peggy go to a different agency, we already knew that the next year we were going to have them merge. That’s something I wouldn’t have done in the past just because I’ve just been like, “Figure it out the next year.” That’s the advantage of having future real estate already invested in. So what have you learned about crafting the end of a series?

Ending a TV show is not organic to the TV writing process. Your whole job is to propel people into the next week, so this is a totally foreign idea in itself. Even when I tried to be really final in some of those season finales, the audience doesn’t see it that way if you’re doing your job right. They want more. That’s your dream. So thinking about where you leave the characters and how it would effect the people who had watched it from the beginning is one thing. Then you think that it will be out there and people who have never seen the show will know it when they start — how does that taint it? That’s what I think is the genius of “The Sopranos” in a way. “The Sopranos” to me, because of the way the story ended, will always exist in some kind of continuum of itself. Now, “Mad Men” is a very different show, so has to find its own ending, and my goal was to find what was the right ending for the story. And I do think about the audience. I do think about what are they going to feel like when it goes off the air. And I’m saying this as someone who has lost their favorite show before. That’s the other mistake you can make: Don’t assume everybody watching your show that it’s their favorite show. But write to the people that you think it is. AWARDS SEASON

I used to wonder, cynically, if they split up seasons to increase the number of awards you’re eligible for.

I don’t know if that’s part of AMC’s strategy. I don’t think there’s been much of a thought as to our eligibility. It’s not why anybody does it, and the promotion and so forth of the show has always been about tune-in. Lionsgate likes it to win awards because it lasts longer, it’s something to put on the DVD and Netflix, and certainly all of us have enjoyed be recognized, but I don’t think anybody was like, “Hey, we don’t want ‘Breaking Bad’ and ‘Mad Men’ going up against each other.” We went up against them the first three or four years we were on the air and we just won everything and they won actor. For a company with no track record and no shows before, AMC is still reeling from this experience. I can say, good or bad, it is not as calculated an awards machine as when I worked at HBO. I’m not saying they don’t want them and I’m not saying there’s no campaigning, but it’s just not on that level — good and bad. But you might be right, I never thought about it. It wasn’t my idea. [Laughs] Perhaps voters discount the first half of a final season because they know the next year will be a bigger deal.

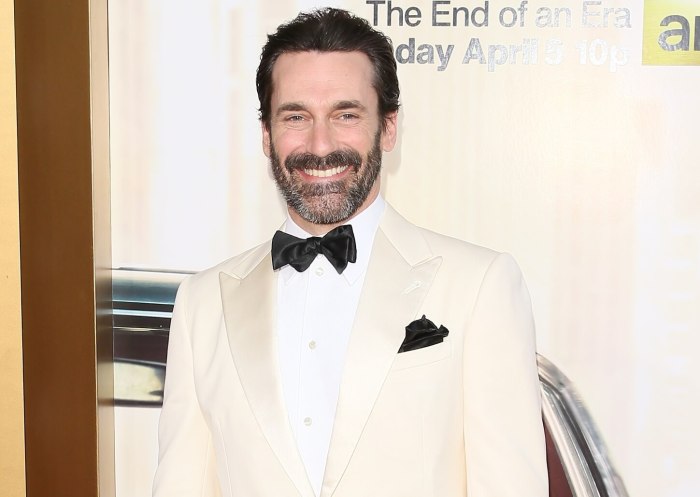

Maybe so, I don’t know how the Academy works. I don’t know how we ever won. You know, how has Jon Hamm not won? I don’t know. But you know, Robert Morse last year — I don’t want to take anything away from Joe Morton or any of the people in that category, but that was the last opportunity, for our show anyway, to reward someone who is however many years old and who did something spectacular. He had a better attitude about it, because he goes, “Don’t you remember last year when we were here and Bob Newhart won his first award?” That guy had been in television at that point for 52 years. To be at that party, to still be considered, to be the old show now, that definitely has not reconciled in my brain. That we are the oldest show on the air at one of these things. NEVER READ THE COMMENTS

How much do you read of pages and pages of Internet devoted to discussing and deconstructing the show?

I go in and out. First of all, there’s so much more of it than there ever was. This year, in particular, there’s even more hypothetical, more tangential. The fans’ relationship is insatiable in a great way. I don’t know that whatever the group of people are that are doing the recaps — some of them are journalists, some of them are up-and-coming journalists, some of them are fans — I don’t know that they necessarily represent the people that watch the show. I don’t think our fan base is particularly active on the Internet, believe it or not. I think they read it, but I don’t think they post. The No. 1 rule of the Internet is “don’t read the comments.”

No, I know that, but here’s two big things, which I have not said to anybody. No. 1 is, let’s say I’ve read everything this year. I am puzzled by if it’s a flaw in the educational system in United States, but the use of the words “symbol” and “symbolism” is puzzling to me. I do not operate in a symbolic universe. There is nothing symbolic in the show. There are things that are referential, there is planting and pay-off, but a symbol is somebody putting their arms out so they look like Jesus. A symbol is like when Peggy did her popsicle pitch and it looked like a medieval tableau of Jesus giving communion, the mother handing out two popsicles. That’s symbolism. I don’t operate in that world. I wish I did. To try and explain to America — maybe this is where they get this idea of symbolism from — but that guy jumping out the window in the credits? That’s happening in his mind. He’s standing there, and then at the end he’s sitting there. That’s his imagination. It’s not literally happening. Do people know that? It’s fascinating to me, and people are entitled to take whatever they can. But what I do resent is the suggestion that in some way we are screwing with the audience, we’re messing with them. I mean, there’s 92 hours of this thing. We’ve tried to tell the story the way that we want to see it. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but I just see this kind of third person, stepping away from it attitude in a lot of these things — which they’re totally entitled to do — and the insinuation is there’s some diabolical force at work. I hate to drag David Chase into this, but the idea that people think that David Chase was toying with them or cruel or sadistic or something with the ending of “The Sopranos” is just mystifying to me. That ending is very emotional for him and for those of us who love the show. It was a surprise, and I can understand that the lack of resolution is frustrating to people who wanted something more definitive. On the other hand, we’re still talking about it 10 years later. He was just talking about it himself, in fact.

I saw that. I mean, the last page of the script was not ripped out. That’s a very skillful storyteller telling you like, “Guess what? The world will go on in one form or another, and these are the things that might happen.” In fact, I always wonder if it had faded to black instead of cutting, if people would’ve had a slightly different emotional thing. But you know what? All of this is a great problem to have. And the experience of having people watch your show, understand it in any way they want to, write about it, obsess with it, enjoy spending time with those characters, recognize themselves in it, that’s your whole goal. And I’m saying that as someone who watches TV. So, opening credits aside, what kind of false symbolism are we talking about?

I was laughing because I got all of these requests about a sombrero in Don’s office in a recent episode — people asking, “What is it? What’s the significance?” I couldn’t remember, so I went and talked to the prop master and set decorator, and they were like, “You said you wanted something fun.” I was like, “Oh, OK.” So I’m talking to David Chase and I go, “This sombrero thing is out of control,” and he goes, “I almost wrote you about that. I thought that was so great. I just saw it in Don’s office and it made me laugh.” I was like, “Are you f—ing with me?” LEARNING FROM THE MASTERS

Not to harp on “The Sopranos” but …

I never tire of talking about it because I bear no responsibility for it and I’m a huge fan.

Specifically its series finale, and other series that have had the luxury of knowing when they’re going to end…

You know what? You can not underestimate that. I have said it over and over again, I cannot believe how lucky we feel to end it when we want to and how we want to.

What aspects of the other shows that have had that luxury did you revisit or took into consideration?

I mean, you don’t want to do what another show did. I’m not going to do “Bob Newhart.” I watch TV, so I am aware of it. I love the “Six Feet Under” ending, I loved “M*A*S*H,” obviously. That was a big event and I just loved how that story with Hawkeye was a different tone from the rest of the show in a great way. It was a gruesome story where the main character was completely estranged from us because he’d had a psychotic break. I’m being very specific about that finale because what was so great about it is it felt to me almost like an episode that they couldn’t have done until the last episode, right? But “The Sopranos” ending, I loved the way “30 Rock” ended, “Mary Tyler Moore” obviously. “Newhart,” the original and the second one. I still get into arguments about how “Lost” ended.

You know what? I was not up to date on the show when that thing ended — because I was working, you don’t get to keep up on these things, and also there’s way more of them than there are of “Mad Men” — so I’m not qualified to talk about that, but I’m a fan of what they do. I was disheartened to see that they were so hard on Damon [Lindelof] and Carlton [Cuse] when they had given them, you know, seven years of intense pleasure. (laughs) You want to earn your ending, but if you’ve done 100 hours of something that people have been watching, you’ve earned everything already. YOU’LL NEVER SEE COMMERCIALS THE SAME AGAIN

I’d imagine you’re something of an advertising expert now.

I’m an expert the way that the coroner is an expert on human life. [Laughs] I am a forensic observer. I’m a consumer, and I certainly know more about it now than when I started. And I believe strongly still that advertising is not about creating want, it’s about reflecting what we want, and the people who are really good at it are tapping into something that we have told them. And the truth is someone who has 25 cents in their pocket is more likely to listen to a message about buying something than someone who has zero. On the other hand, I don’t think I’d be very good at it. I’m good at criticizing it or understanding how it works and appreciating it. And also, in a culture that’s so split up into pieces — which it always has been — there is something about an ad that is one of the last common reference points, do you know what I mean? “That ad,” right? I mean, my children have seen “Casablanca” and “The Wizard of Oz,” but I don’t think there’s much left that we’re all supposed to know. “Terminator,” maybe, still seeps through. “I’ll be back.” [Laughs] I grew up watching a lot of referential comedy, like Mel Brooks.

Someone pointed this out to me, that it’s actually part of the esthetic of the Millennials — who are going to be as big and influential as the Boomers were — that paying attention to old references makes you an old person. Whereas when I was growing up — which is the worst thing you can say to make yourself sound young — it was considered ignorant to not know, for example, who Humphrey Bogart was. I’ll use “Gone with the Wind” as an example. For some reason “Gone with the Wind” is not part of the Millennial references. “I Love Lucy” is, maybe because it’s on TV all the time. But I talk about it sometimes and people sometimes treat it like it’s some old art movie, and it was the most successful movie ever. To hear my mother-in-law who was a Holocaust survivor and grew up in Hungary talk about seeing it — that was allowed, that made it through. Charlie Chaplin, I think, is still one of the most recognizable characters in the world — as is Columbo, by the way. Neither of which are really supposed to be part of a Millennial sensibility — and I’m generalizing, obviously, but I do think it’s out of style to be interested in that. You kind of get embarrassed and like, “Oh my God, my references are old.” Or they’re making a reference and don’t even know it.

There was a kid who was in a debate tournament and he was talking about “putting out a fire with gasoline,” and that he had heard some rapper say it. And I said, “Well it’s an old expression, it’s very good, but David Bowie said it for sure.” [Laughs] I don’t think he invented it, but it doesn’t matter. References are an interesting thing. But advertising — even if people see it as an intrusion — it can be a form of entertainment. And when we love advertising, we really, really love it. That’s my relationship to, it’s academic. I know one thing, which the show may have eradicated in some way, which pleases me, is that the reputation of the ad man as someone who is untrustworthy, self-serving, destructive, noisy, whatever — ruining our lives — I think that we’ve at least let people know that human beings do that job and they shouldn’t be so mean about it. It used to be that every yuppie movie character who needs to learn the error of his ways in a movie worked in advertising.

Like architecture, it’s kind of an ideal thing for writers because it’s a creative job that makes money. America is constantly giving the message in almost all of its entertainment, “Do you want to be valuable or do you want to make money? Can you do both?” And that tension — which is a lot of “Mad Men,” by the way — that was always the great thing. Architecture was the other thing because it was so artsy and everything, but what people don’t realize is that architects don’t make any money. [Laughs] And ad people do.