NEW YORK (Reuters) – A special strain of New Yorker showed up at Chelsea Piers Fitness on Wednesday morning, the first time gyms have been allowed to open since the coronavirus pandemic shuttered the city in March.

Broad-shouldered giants insisted through mandatory face masks that, despite nearly 200 pounds of visual evidence to the contrary, they had withered away over five months. Women with sleeked-back ponytails and pronounced abs, tired of months of quiet apartment workouts respectful of downstairs neighbors, let heavy barbells crash to the ground.

In short, it was a communion, in one of Manhattan’s most body-conscious neighborhoods, of those for whom the gym is not a chore but a kind of church.

“I’d forgotten this feeling right now, what it’s about to feel like,” Justin Silver, a stand-up comic and dog trainer, said as he settled into a leg press machine. He raised his feet in rapture as quadriceps ballooned out of his thighs.

“Oh my God. I love it!”

Gyms, unfairly in the view of some devotees, were seen as riskier than other joints. New Yorkers have been able to dine outdoors at restaurants and shop in non-essential businesses since June, and visit bowling alleys and museums since August.

Last month, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said gyms could reopen statewide with the local mayor’s blessing as long as local health departments enforce new safety rules to contain a virus that spreads more easily in confined spaces.

Gyms must operate at 33% capacity, with floors rearranged so patrons can exercise more than 6 feet apart. Gym owners whose revenue had been decimated while paying rent on empty premises had to upgrade air-conditioning systems to meet at least MERV-13 filtration standards. Patrons must attest to their good health and prove to a remote thermometer aimed at their foreheads that they have no fever.

Both the Equinox and Crunch Fitness gym chains have bought back-pack mounted electrostatic disinfecting sprayers to douse equipment throughout the day.

“We’ve spent the last three or four months planning and preparing to reopen under this new world order,” Crunch Chief Executive Keith Worts said in an interview.

Mandatory masks that cover the mouth and nose annoyed some at Chelsea Piers.

“I’ve got to get a better mask,” personal trainer Rachel Mariotti, 31, said through hers. “I could barely breathe.”

After a few minutes, she abandoned cardio on a skier machine for powerlifting.

Like others at the gym, Mariotti said she was reassured by the safety measures: it seemed to her less risky than prolonged rides on the relatively more crowded subway.

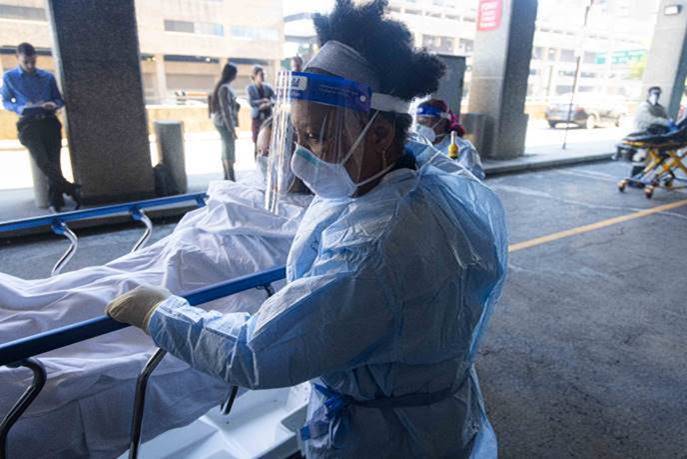

The gym’s denizens were forced to improvise from March, when New York became the global pandemic epicenter and morgue trucks dotted the streets, to September, with more than 99% of all COVID-19 tests in the city coming back negative.

They fiddled at home with resistance bands bought online at a pandemic mark-up, or did pull-ups on city scaffolding, or, craving more than bodyweight, convinced a girlfriend to sit on their backs while they did push-ups.

But none of that could replace the gym’s clatter and black iron.

Ian Lane, a 31-year-old Brooklynite who works in events management, took up running loops around Prospect Park, which wrecked his gains from weight-lifting.

“I have lost 20 pounds of muscle over the last six months, so I’ve a lot of catching up to do. You can only do so many push-ups at home,” he said.

With an upward gaze, Lane resumed cautiously, squatting with only a 135-pound barbell on his back, far short of the 225 pounds he could pump for six reps at the start of the year.

(Reporting by Jonathan Allen; Editing by Richard Chang)