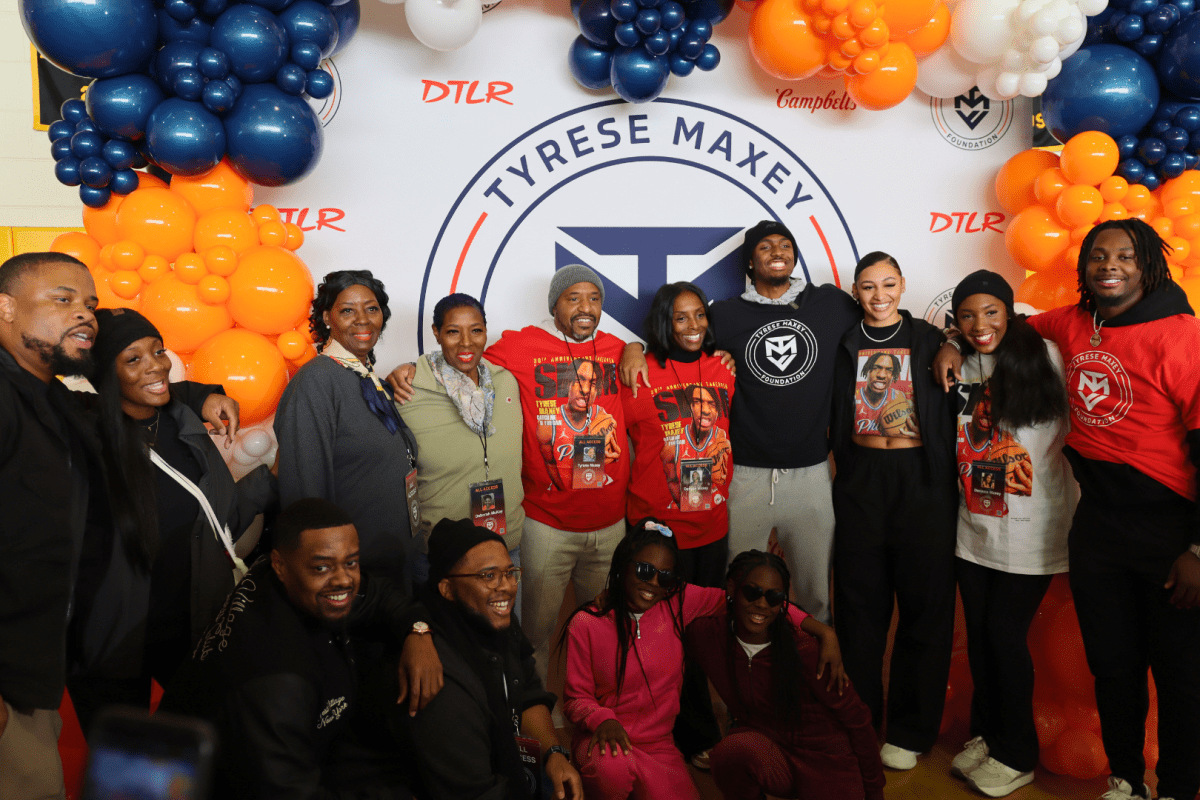

Community policing would, in part, involve cops more with shop owners and residents. Credit: Miles Dixon/Metro

Community policing would, in part, involve cops more with shop owners and residents. Credit: Miles Dixon/Metro

Community policing has become a mantra in the progressive political world over the past year. Mayor Bill de Blasio and Police Commissioner Bill Bratton have vowed to make it a core principle of the NYPD’s approach to public safety.

But the catchphrase has rarely been explicitly and specifically defined. There has been no clear picture drawn of what the new approach would look like in practice.

It has been attempted before — by former Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, in fact, back in 1992 and 1993 before he passed on leadership of the NYPD to Bratton for the first time.

Cops who were around at that time say it was flawed back then.

“The actual practice of it didn’t really seem to work the way it should have,” said Carolyn Taylor, a former cop who retired as a sergeant in 2001.

Taylor explained that rather than training the whole force to operate differently in the field, there were specific community policing officers assigned to specific beats. They were tasked with interacting with the community and addressing issues within their specific areas.

“But they became far removed from doing the actual job of a police officer,” Taylor said. “It took a lot of manpower away from responding to emergencies.”

Some people were more blunt.

“To be honest with you, I think community policing is a big joke,” said Ed Mullins, president of the sergeants union.

“I think it’s a feel-good for the public,” he continued. “They do this big group-hug thing that accomplishes nothing.”

He described the same practice: specific community policing units, with officers assigned to certain streets in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“You couldn’t use them if you were short a sector car, you couldn’t use them if something happens,” Mullins said.

“If community policing were to be implemented, [first] they’d have to change the name so they’d remove the past stigmas,” Mullins advised.

And it seems that “they” are doing just that — Bratton appears to increasingly be moving away from de Blasio’s campaign mantra of “community policing” to a new terminology: “collaborative policing.”

There is another obstacle to effective community — or collaborative — policing, according to both former and active duty cops: the number of cops in the NYPD has decreased.

Eugene O’Donnell, a former cop who now teaches police students at John Jay College, noted there “doesn’t seem to be any real appetite to make it bigger.” If anything, there appears to be a push in the opposite direction.

“It seems to be shrinking, and there doesn’t seem to be a plan to stop the shrinkage,” O’Donnell said.

The NYPD practices “minimum manning,” meaning there are a certain number of police officers that must be on patrol at all times.

But O’Donnell said that number doesn’t necessarily mean beat cops out on the street, and Taylor agreed that the number of people actually out on patrol “can be skewed.”

Of the officers assigned to a specific precinct, a number of them may be deployed into detective bureaus, or out on steady tours. The numbers of cops out on patrol are “not necessarily evenly distributed on a daily basis.”

The number of detectives on duty or assigned to a given precinct is particularly tricky, O’Donnell said, and there are homicides that are going unsolved when they needn’t be.

“There’s some evidence they’re not solving the crimes they should be solving,” O’Donnell said.

Lt. Louis Turco, an active duty cop with the lieutenants’ union, said community policing “had some valid points to it,” but agreed it would require more officers than the NYPD currently has.

“I think it’s a good tool to have that out in the communities,” he said. “The problem is you need to increase the manpower.”

The idea, Turco said, is to not separate out specific community policing cops.

Cops walking the beat would stop into businesses, meet people, build relationships with them. Storeowners and residents would get to know and become comfortable with those officers, and the officers would gain a better understanding of the area and the needs of the community.

But these officers wouldn’t be separated from the police force — if anything, they would be more likely to respond to 911 calls in the area where they were working.

And that would be beneficial too.

If officers are just responding to 911 calls all the time, Turco said, “it becomes very impersonal.” But when the responding officers are people the victims have gotten to know, it gives them a greater sense of safety and security.

Ultimately, Turco said, having someone walk the same beat regularly allows the community to get to know them better, and there are no downsides to that.

But he maintained, “With the number of officers we have now, you just can’t get that done.”

Bratton has reportedly said the same, not too long ago.

In June, many months before de Blasio appointed him police commissioner — well before de Blasio even seemed to have a chance of winning the primary election — Bratton spoke at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative thinktank where the strategy of proactive policing was first developed.

According to Capital New York, Bratton attributed the problems with stop-and-frisk to the diminished size of the police force, which he said was a result of a “political decision” under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg due to “budgetary needs [and] with the justification that crime was down so dramatically.”

“Budget decisions were made to reduce the size of the police force from 41,000 to about 34-35,000,” he reportedly said. He estimated that cut amounted to “a loss of about 80 officers per precinct.”

Bratton also blamed the decreased size of the police force for Operation Impact, a program he has been critical of, which stations rookie cops in high-crime areas. A lack of supervision by more experienced cops led to “huge numbers of stop-and-frisk incidents,” Bratton reportedly said.

Taylor also noted the issue of Impact cops being inadequately prepared.

“They’re brand new out of the academy, and they’re actually still training, so they still don’t know what their description is,” Taylor said. “They’re basically there just to have a body present, which does create its own feelings of safety.”

Capital separately quotedBratton saying the decreased police force became “too small” to assign cops to specific beats long-term, enabling them to develop relationships with local residents and collaboratively work to reduce crime.

Bratton seems to have changed his mind, however.

Following his first press conference as police commissioner, Bratton dismissed a question about the size of the force being a hindrance to effective community policing.

“The size of the force has nothing to do with the ability to do collaborative or community policing,” Bratton said.

Follow Danielle Tcholakian on Twitter @danielleiat