NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) — Officials close to peace talks aimed at ending Ethiopia’s deadly two-year war confirmed the full text of the signed accord on Thursday, but a key question remains: What led Tigray regional leaders to agree to terms that include rapid disarmament and full federal government control?

A day after the warring sides signed a “permanent cessation of hostilities” in a war that is believed to have killed hundreds of thousands of people, none of the negotiators were talking about how they arrived at it.

The complete agreement has not been made public, but the officials confirmed that a copy obtained by The Associated Press was the final document. They spoke on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to discuss it publicly.

At Wednesday’s signing, the lead negotiator for Tigray described it as containing “painful concessions.”

One of the pact’s priorities is to swiftly disarm Tigray forces of heavy weapons, and take away their “light weapons” within 30 days. Senior commanders on both sides are to meet within five days.

Ethiopian security forces will take full control of “all federal facilities, installations, and major infrastructure … within the Tigray region,” and an interim regional administration will be established after dialogue between the parties, the accord says. The terrorist designation for the Tigray People’s Liberation Front party will be lifted.

If implemented, the agreement should mark an end to the devastating conflict in Africa’s second-most populous country. Millions of people have been displaced and many left near famine under a blockade of the Tigray region of more than 5 million people. Abuses have been documented on all sides.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed asserted that his government received everything it asked for in the peace talks.

“During the negotiation in South Africa, Ethiopia’s peace proposal has been accepted 100%,” and the government is ready to “open our hearts” for peace to prevail, Abiy said in a speech. He added that the issue of contested areas, seen as one of the most difficult, will be resolved only through the law of the land and negotiations.

Neither Ethiopian government nor Tigray negotiators responded to questions.

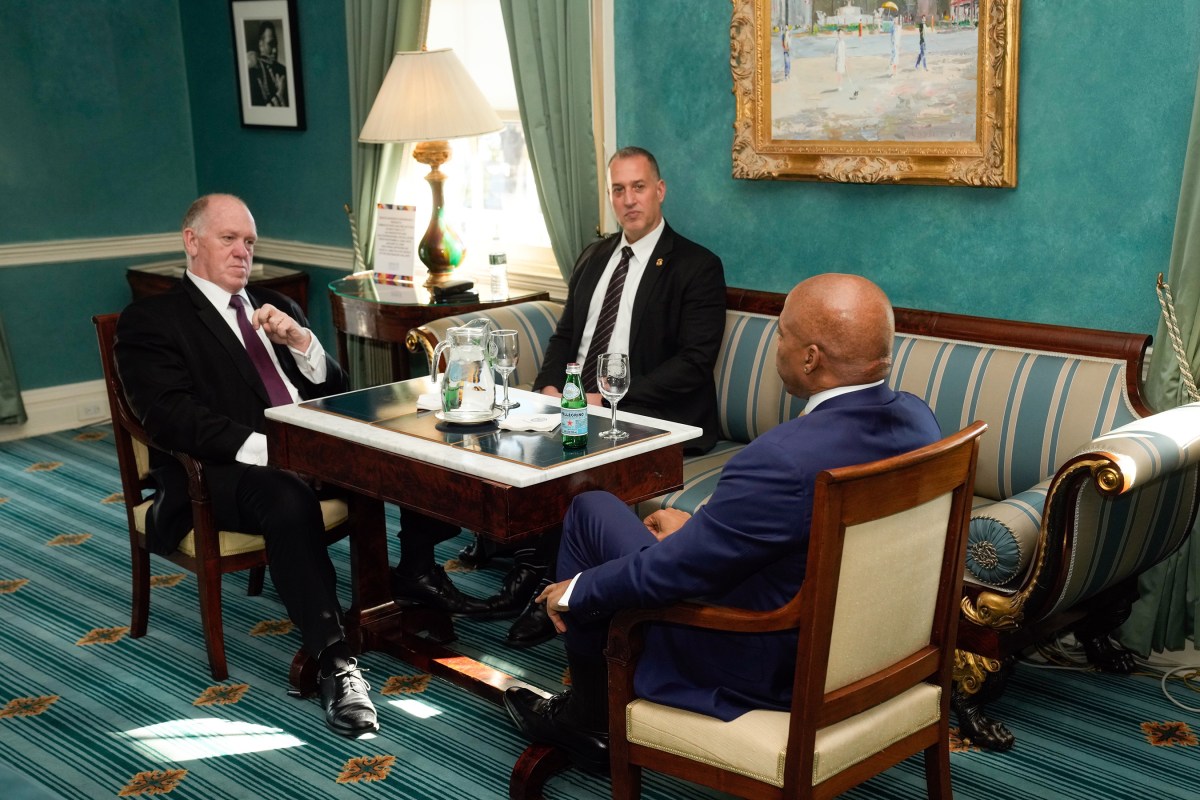

As part of the full agreement, both sides agreed not to make any unilateral statement that would undermine it. The deal also calls for the immediate “cessation of all forms of hostile propaganda, rhetoric and hate speech.” The conflict has been marked by language that U.S. special envoy Mike Hammer, who helped with the peace talks, has described as having “a high level of toxicity.”

“The human cost of this conflict has been devastating. I urge all Ethiopians to seize this opportunity for peace,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told reporters Thursday, one of many messages from observers expressing cautious hope.

Enormous challenges lie ahead. The opaque and repressive government of neighboring Eritrea, whose forces have fought alongside Ethiopian ones, has not commented, and it was not clear whether Eritrean forces had begun to withdraw. The agreement says Ethiopian forces will be deployed along the borders and “ensure that there will be no provocation or incursion from either side of the border.”

Mustafa Yusuf Ali, an analyst with the Horn International Institute for Strategic Studies, said trust-building will be crucial. The agreement “needs to be coordinated, it needs to be systematic, and above all it needs to be sequenced so that the Tigrayans are not left to their devices after handing in all their weapons then suddenly they are attacked by the center,” he said.

The agreement sets deadlines for disarmament but little else, although it says Ethiopia’s government will “expedite the provision of humanitarian aid” and “expedite and coordinate the restoration of essential services in the Tigray region within agreed time frames.”

The United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross said they had not yet resumed the delivery of humanitarian aid to Tigray, whose communication, transportation and banking links have been largely severed since fighting began. Some basic medicines have run out.

“It’s not surprising that it may take a little bit of time to get the word out to the competent authorities in the field. We are in touch with them and trying to get that unimpeded access as soon as possible,” the spokesman for the U.N. secretary-general, Stephane Dujarric, told reporters.

A humanitarian worker in Tigray’s second-largest town, Shire, said there had been no sounds of gunfire over the past few days but people and vehicles were still blocked from moving freely. It was also quiet in the town of Axum, another humanitarian worker said. Both spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Residents of the Tigray regional capital, Mekele, nervously waited for next steps.

Asked about the peace agreement, resident Gidey Tsadik replied, “It’s good. Everyone is happy. However, it’s not known when exactly we will have that peace.”

Tedros Hiwot said residents hadn’t heard when basic services will resume. “We need it to happen quickly,” he said.

Tigrayans outside the region said they still could not reach their families by phone. “I hope that this will be an opportunity to reconnect with my family,” said Andom Gebreyesus, who lives in Kenya. “I miss them and I don’t know if they are alive.”

At a memorial service in the capital, Addis Ababa, for soldiers killed in the conflict, Defense Minister Abraham Belay spoke of “the very complex and tough reconstruction work that lies ahead of us.”

Associated Press writers Desmond Tiro in Nairobi, Kenya, and Edith M. Lederer at the United Nations contributed to this report.