TOKYO (Reuters) -New Zealand’s Laurel Hubbard made history on Monday by becoming the first openly transgender athlete to compete at an Olympic Games in a different gender category to that assigned at birth, but she suffered a disappointing early exit from the women’s +87 kg final after three no lifts in the snatch.

At 43, Hubbard was the oldest competitor in the weightlifting in Tokyo, in which her inclusion has ignited a fierce debate about fairness for women and about gender identification and inclusivity.

Hubbard was assigned male at birth and competed in weightlifting at junior level. She transitioned eight years ago, resumed weightlifting and became eligible for the Games under a 2015 International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus allowing transgender athletes to compete in women’s events.

Another athlete who came out as transgender last year, Quinn, a member of the Canadian women’s soccer team, continues to compete in the gender category which they were assigned at birth.

Hubbard’s landmark appearance in Monday’s competition lasted just 10 minutes, with each of her first three efforts in the snatch ruled no lifts.

Hubbard walked confidently on to the stage, smiling amid yells of encouragement from an arena that was officially closed to spectators, but made busy by fellow athletes and a swarm of international media.

She cleared the bar above her head on the second attempt at 125 kg and there was a brief celebratory moment of triumph, clenched fists and loud cheers, but it was cut short by the judges who declared it a no lift.

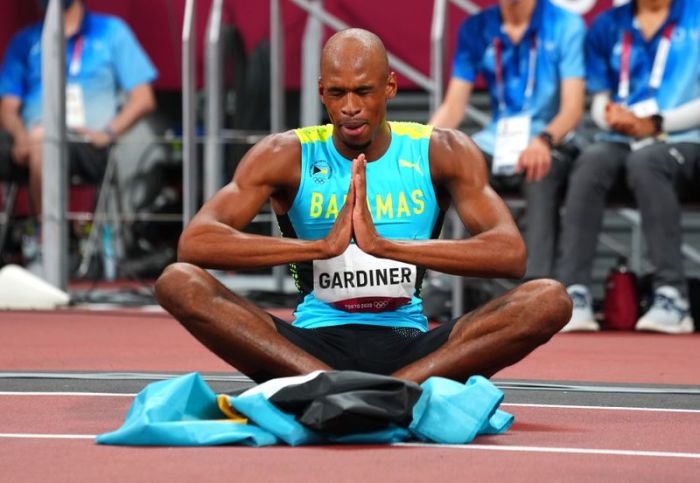

She failed again in the decisive third attempt but stepped forward, to wave to the arena, hands clasped together in appreciation and an awkward smile as applause rang out.

“I’m not entirely unaware of the controversy which surrounds my participation at these Games,” Hubbard told reporters, eyes closed and wearing a baseball cap.

“And as such, I would particularly like to thank the IOC, for I think really affirming its commitment to the principles of Olympism and establishing that sport is something for all people, that it is inclusive and is accessible.”

Hubbard, who declined to answer questions, had been tipped for a medal in Tokyo having won a world championship silver in 2017 and Oceania championship gold in 2019.

She was twice the average age of her competitors, and a medal would have made her the oldest weightlifter to reach an Olympic podium by three years.

DIVISIVE INCLUSION

Nevertheless, some former athletes and women’s rights advocates say that Hubbard had an unfair physiological advantage and that her competing in Tokyo undermined the struggle for greater equality for women in sport.

Trans activists argue, however, that hormone therapy puts athletes who make the transition at a performance disadvantage and say huge physiological differences already exist between competitors within men’s and women’s categories.

Under the IOC guidelines, transgender athletes can compete as a woman provided their testosterone levels are under 10 nanomoles per litre for at least 12 months before their first competition.

The IOC is reviewing those guidelines and aims to establish a framework that would allow sports federations to take decisions themselves on transgender participation.

Hubbard’s competitors were largely guarded on Monday in their responses to questions about her inclusion, many declining to comment and others saying they were focusing purely on their own performances.

“I’m here to talk about Sarah Robles USA,” said bronze medallist Sarah Robles, when asked about Hubbard.

Silver medallist Emily Campbell of Britain had a similar response.

“I’m going to be selfish today. It’s all about me because I worked hard for this,” she said, holding up her medal.

But there were words of encouragement for Hubbard and confidence that the IOC had made rules to ensure fairness.

“I was really sad she made three no lifts,” said Austria’s Sarah Fischer.

“She had a hard background and so many people wanted her to lose. She had an uphill battle here.”

“Actually I wanted her to win a medal. That would be the best, then everyone would shut up about it.”

(Additional reporting by Junko Fujita; Editing by Hugh Lawson)