(Reuters) – Brian Miller would have one of the toughest jobs in Washington even without the cutthroat politics all around him. As America’s inspector general for pandemic relief, he’s charged with rooting out fraud in the spending of trillions of dollars in emergency aid.

But before even starting work, he was blasted by Democratic lawmakers who say he’ll be more of a lapdog than watchdog, citing his recent history as a lawyer in Donald Trump’s White House. And Trump himself – who in recent months has ousted a raft of inspectors general, prosecutors and other officials – signaled that he’ll keep Miller on a tight leash, forbidding him from reporting to Congress without “presidential supervision.”

How Miller, a Trump appointee, handles such pressures will test the administration’s willingness – or lack of it – to demand accountability in pandemic relief spending. Miller’s response also could make or break the reputation the veteran prosecutor and inspector general has built over decades.

Reuters interviewed more than two dozen people who know Miller or have insight into the job confronting him to understand how he might tackle it. Supporters from across the political spectrum expect Miller to investigate aggressively and impartially. They say he has prosecuted high-profile cases and weathered political controversy as an inspector general – including an uproar over an investigation he led that forced the resignation of the Republican chief of the General Services Administration (GSA).

But the new post – Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery – poses far higher logistical and political hurdles for the 64-year-old attorney, a Presbyterian elder who married his high school sweetheart and lives in a modest ranch house in Fredericksburg, Va.

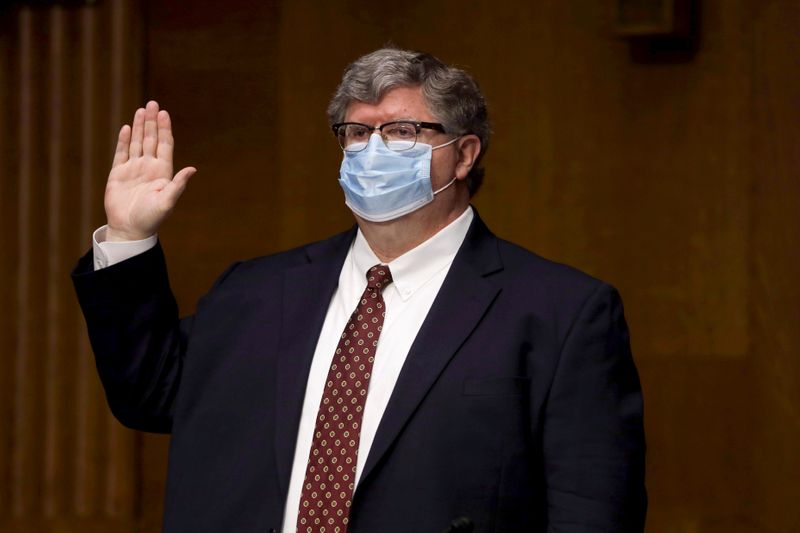

Miller declined to comment for this story. He acknowledged that the position will be “very challenging and demanding” during his Congressional vetting on May 5.

Gordon Heddell, who has served inspector-general stints at the Labor and Defense departments, called Miller’s work “outstanding” in his job at the GSA. Still, Heddell said, any inspector general under Trump has to expect “a day of reckoning.”

White House spokeswoman Sarah Matthews declined to comment on concerns that Miller’s independence could be compromised by his recent White House work and Trump’s record of firing inspector generals.

Miller’s appointment, announced in April, places him at the center of a roiling battle over transparency in pandemic spending. The administration initially fought to keep secret the names and loan amounts of recipients in a $660 billion program offering forgivable loans to businesses. The Treasury Department has since agreed to disclose information for awards over $150,000 – a threshold Democratic critics say will still hide most payments. The administration has said it will balance transparency concerns with protecting what it calls confidential business information.

The White House also took heat from lawmakers for issuing guidance they said allows federal agencies to ignore legislative mandates to collect and report details on how aid recipients spend the money to save jobs. The legislation calls for reporting that information to the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee – of which Miller is a member. [nL1N2DV1ZA]

Miller’s remit focuses immediately on a $500 billion portion of the aid package administered by the Treasury Department, such as airline bailouts and funding for Federal Reserve emergency lending. But the law opens the door for him to oversee other bailouts, including the business loan program.

Skeptics of Miller mostly cite his most recent job, as a senior associate White House counsel starting in December 2018. While he generally kept a low profile, Miller angered Democrats with a letter denying a Congressional watchdog agency’s information request related to the Ukraine impeachment inquiry.

“Trump is making appointments based on loyalty,” said Virginia Canter, ethics counsel at the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington and a former White House lawyer under two Democratic presidents. “So you have to ask yourself: Can you commit yourself to representing the public interest when your past job was being the president’s lawyer?”

Democratic lawmakers have been more blunt. Trump “put a fox in charge of the henhouse,” said Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal in a statement.

FROM THEOLOGY TO LAW

Former colleagues describe Miller as a serious and unpretentious veteran attorney. Before entering the law, Miller had planned a career in the church. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Temple University in Philadelphia, and dual master’s degrees from nearby Westminster Theological Seminary. When he didn’t immediately find a position, he went to law school at the University of Texas, graduating in 1983.

Miller is active at the small Presbyterian church in the Washington suburbs, where his son is the pastor. His minister at a previous church, Bob Becker, calls Miller humble and grounded, with a “heart of service.”

After a few years in private practice, Miller in 1987 joined the Washington-based U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and in 1990 moved to the Justice Department, where we worked for 15 years. Some of his best-known work came as a prosecutor in the Eastern District of Virginia, a high-profile outpost dubbed the “rocket docket” for its fast-moving cases.

During that time, Ed Gibson was a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent investigating money-laundering cases. He remembers Miller pulling him aside when he wanted a more severe punishment for a white-collar conviction. Miller asked Gibson something that sticks with him today: “Ed, is that really what you want? Isn’t it justice you are seeking?”

Miller embraced difficult cases, including the complicated prosecution of a physician accused of overprescribing opioids – known as “Dr. Feelgood” – and that of Zacarias Moussaoui, who helped plan the September 11, 2001 attacks.

“He was just tremendous,” said Gene Rossi, a fellow prosecutor at the time who credits Miller’s calm diplomacy with saving the opioid case.

TERRORIZING REPUBLICANS

Former colleagues say Miller didn’t hesitate to take on the Republican leadership of the GSA, a sprawling agency coordinating billions in spending.

During nine years there as inspector general, starting in 2005, Miller was an aggressive watchdog – so much so that the agency’s chief, Lurita Doan, once suggested he and his staff were practicing a form of terrorism, according to a Washington Post report at the time.

Doan froze hiring in Miller’s office and tried to cut its spending. GSA staff filed complaints against Miller, and Congress members called on President George W. Bush to fire him, according to Congressional hearings and reports.

Undeterred, Miller revealed that Doan had steered a GSA contract to a friend, among other interventions. Congress excoriated Doan, who resigned under pressure in 2008. Doan denied wrongdoing at the time; she did not respond to a request for comment.

“What ultimately came out vindicated Brian,” said Ted Stehney, the former head of audits in Miller’s GSA office.

Miller later drove an investigation into a lavish GSA staff event near Las Vegas that resulted in the resignation of the agency’s new chief, Martha Johnson, an appointee of President Barack Obama.

Ex-GSA chief Johnson – who was not directly involved in planning the conference and supported Miller’s investigation – called him a diligent auditor but said his passions could be small-minded. While he unearthed the conference spending abuses, Johnson said, “It was like ‘really’?’ GSA is in the thick of all-of-government spending – federal, state, local, tribal, war theater – and this is what he was fussing with?”

Miller is as parsimonious in his personal life as he expects others to be in government. Stehney, the former GSA colleague, said Miller has always wanted a Cadillac but never bought one.

“He loved to ride in mine, but he still drove his Honda hybrid,” he said.

‘DUTY TO SERVE’

Some associates were surprised when Miller departed from his usual nonpartisan practices by taking a White House job.

Miller told a friend he wanted to get back to public-sector work after a stint in private practice, defending clients from government investigations. Miller told the friend that he “felt a duty to serve” when approached about the White House job.

The few details that have emerged from Miller’s White House work have fueled concerns over his independence.

Democrats called Miller’s denial of a Government Accountability Office (GAO) request regarding the impeachment inquiry improper. Miller downplayed the letter in the May Congressional hearing as “answering the mail,” saying he merely referred the matter to the White House Office of Management and Budget, which had previously responded, providing some information but denying other requests.

He also received an ethics waiver allowing him to continue working with current GSA head Emily Murphy after taking his White House role. While in private practice, Miller had advised Murphy during a GSA inspector-general probe into the cancellation of a relocation of the FBI’s Washington headquarters. The move could’ve hurt revenue at Trump’s nearby hotel.

A friend of Miller from Washington legal circles, speaking on condition of anonymity, said he understood the raised eyebrows over Miller’s White House work.

“If I didn’t know Brian, I would be suspicious given what Trump has done with the IG community,” the friend said. “But he’s Brian. He will do his job, and if it means he gets fired for it, he gets fired for it.”

(Reporting by Lawrence Delevingne, Chris Prentice and Koh Gui Qing; Additional reporting by Pete Schroeder; Editing by Tom Lasseter and Brian Thevenot)