GENEVA (Reuters) – Russia and China have opposed a candidate from Fiji seen as a staunch human rights defender to lead the top U.N. rights body, diplomats and observers say, creating a deadlock just as Washington may seek to rejoin the forum it quit in 2018.

The Human Rights Council presidency rotates annually between regions and is usually agreed by consensus, with any contests typically resolved quickly and cordially, diplomats say.

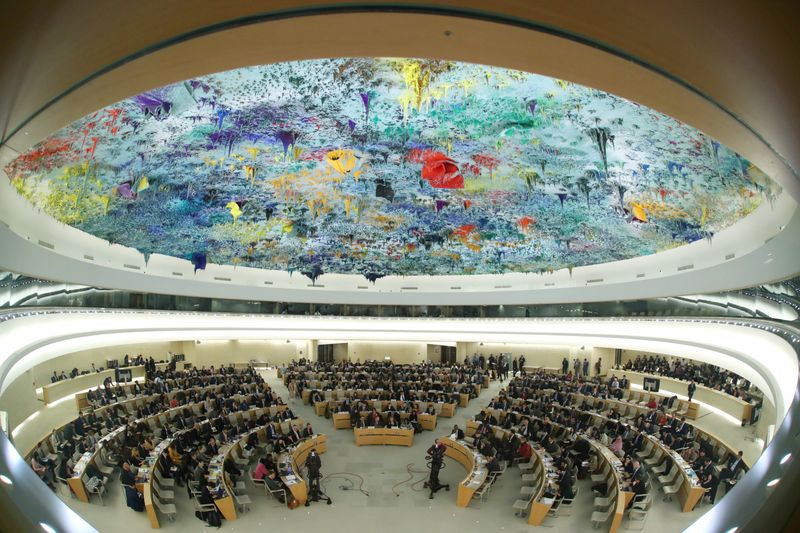

The impasse means the council, the only intergovernmental global body to promote and protect human rights worldwide, is set to resume work in Geneva next week with no leader for the first time in its 15-year history.

While its decisions are not legally binding, they carry political weight and can authorise probes into violations.

The infighting points to a high-stakes game where powers are seeking to pre-emptively counter future influence of the United States, which could rejoin the body under President-elect Joe Biden, Marc Limon of the Universal Rights Group think-tank said.

“Neither China nor Russia want a human rights-friendly country to hold the presidency in a year where the U.S. will probably re-engage with the council,” he said.

Russia, China and Saudi Arabia — sometimes acting through proxies — have opposed the selection of Fiji’s ambassador, Nazhat Shameem Khan, or thrown their weight behind other last-minute candidates, observers and two diplomats said.

“It’s understood that Saudi Arabia, China and Russia were all supportive of a Bahraini candidacy and opposed to a Fijian candidacy,” said Phil Lynch, director of the International Service for Human Rights, citing Fiji’s record, with Khan backing probes into abuses in Belarus and Yemen last year.

The NGO is accredited to the council and takes part in debates.

A Chinese diplomat said on Friday he would be “happy to see any of these candidates as president”.

The diplomatic missions for Fiji, Russia and Saudi Arabia did not respond to requests for comment.

Khan has not stepped aside and alternative candidates from Bahrain and Uzbekistan put forward since December have also faced opposition, diplomats said.

“This mess potentially strengthens those voices that argue HRC is anti-democratic, dysfunctional etc, and U.S. should not re-engage (or insist on big reforms as price for doing so),” said the International Crisis Group’s Richard Gowan.

A review that could prompt reforms of the forum is pending.

Currently, members have to be elected onto the 47-member council to vote in it – but that may be one of the subjects considered in any reform. China and Russia both return to the council this year.

The council president has limited powers although some say the role has become increasingly political.

The president does however appoint independent experts, such as the one who led an inquiry into the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Attempts by Oman, last year’s Asia-Pacific group coordinator, to resolve the matter via secret ballot hit Qatari opposition, creating a deadlock one diplomat called “a mess”.

One way to resolve the impasse might be a vote at the council next week, diplomats say.

(Reporting by Emma Farge; Editing by Stephanie Nebehay and Alison Williams)