A woman shouts at a busload of students to “Go home and stay home” in September 1974. Credit: Boston Globe

A woman shouts at a busload of students to “Go home and stay home” in September 1974. Credit: Boston Globe

Friday marks the 40th anniversary of the implementation of a court ordered desegregation of the city’s schools. The so-called busing crisis was an ugly tumult that typified a city divided by race; there were protests, riots and violence in the streets and in the schools.

The fallout from Judge W. Arthur Garrity’s decision cemented Boston’s reputation as a racist city. Its legacy is still a matter of debate.

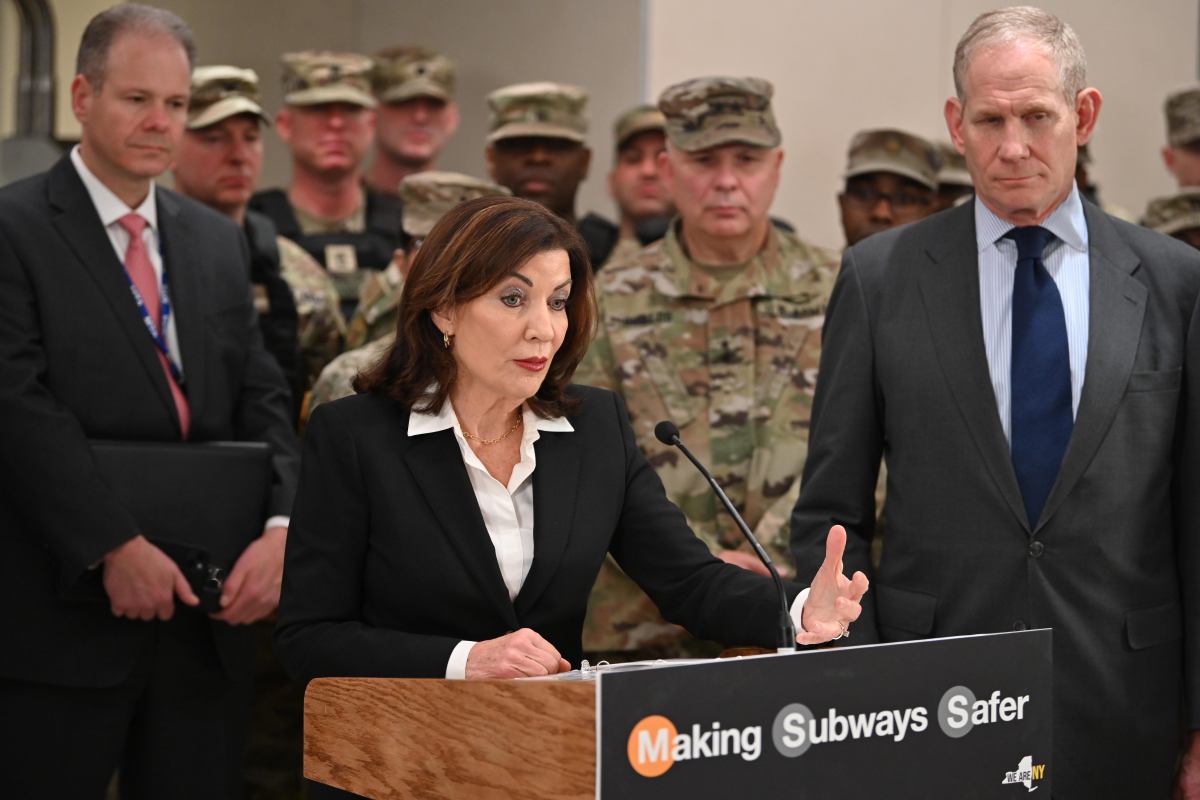

Ray Flynn, the former Boston mayor who was a Southie state rep at the time, says while Garrity’s decision was the right one, the implementation of the court order was a disaster.

“The real story that’s never been told is that this had no positive influence on improving the quality of education for all of Boston’s children,” he said. “It did nothing to educate children or prepare them for a more promising future. The children and parents suffered.”

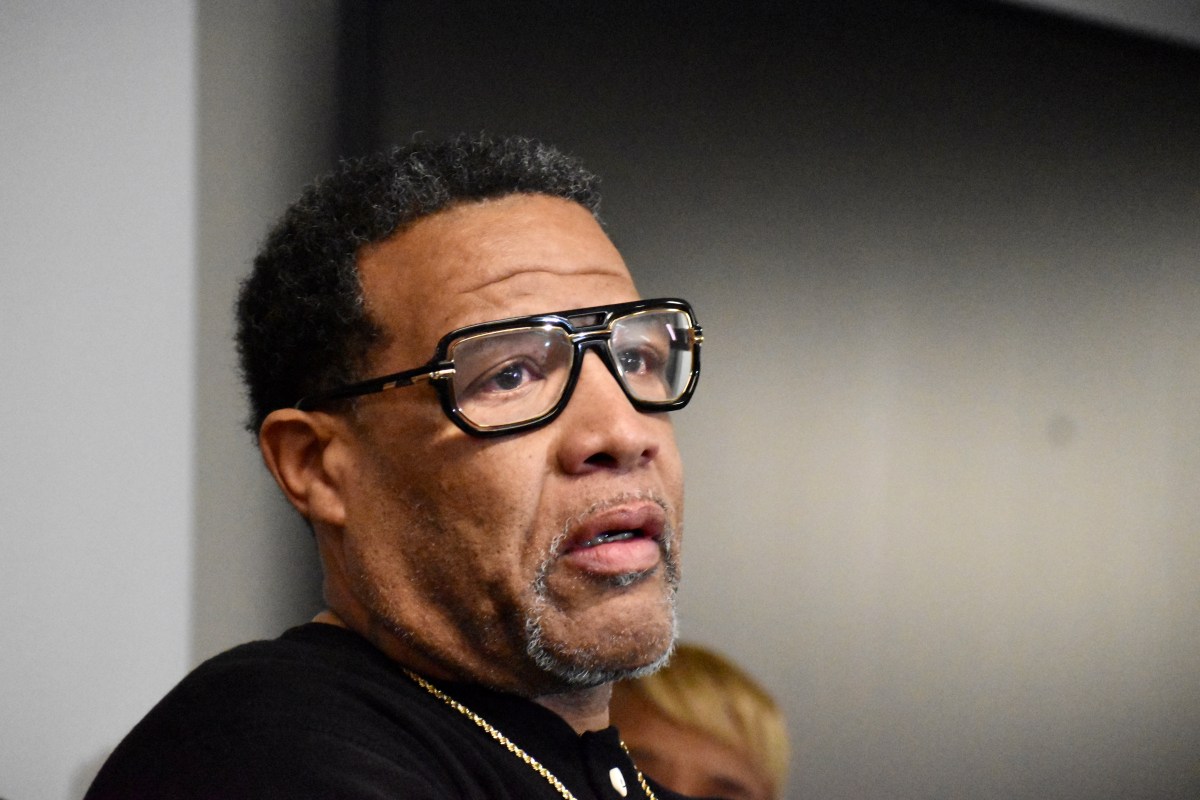

Kevin Peterson, a senior fellow at UMass Boston’s Center for Collaborative Leadership, has a decidedly different take. He says the takeaway has been positive; Boston has become less divided since 1974, in no small part due to the forced desegregation.

“The legacy, 40 years later, is positive,” he said. “There were extreme growing pains in the city, beyond which we matured and learned lessons. I think we’re more united now than we’ve ever been before.”

While acknowledging the initial years of desegregation were ugly and painful for thousands, Peterson said the busing was unavoidable and “extremely instrument in terms of initiating a new era in Boston, which had been terribly separated by race.”

Should anything have been done differently?

“Emphatically, no,” said Peterson. “I think Judge Garrity’s decision to push the issue around racial integration was one of the wisest judicial decisions in the country. Boston stood as an example of northern racial segregation. It was a wise but painful decision.”

Flynn said there should have been more communication with parents before the implementation of the forced busing as well as a significant injection of government cash to improve the city’s school curriculum and infrastructure. Those things, said Flynn, could have eased tensions.

“You’re getting married, you meet the bride’s family beforehand,” said Flynn. “You don’t show up the day of the wedding and nobody knows each other.”

He added, “It was very a divided time and nothing else works if you have a racially divided city. Public transportation doesn’t work, education doesn’t work, (after school) sports programs don’t work, nothing works. Boston gradually came together.”