(This July 27 story corrects title of Adia McClellan-Winfrey in paragraph 15.)

WASHINGTON(Reuters) – Joyce Elliott, an Arkansas state senator who is seeking a U.S. congressional seat in November, was the second Black student to attend her local public high school; the first was her older sister. If elected in November, she will be the first Black lawmaker in Congress from Arkansas, ever.

On the campaign trail in June, Elliott attended a demonstration against racism in White County, which is more than 90% white, and spoke to attendees in the shadow of a Confederate monument.

The November election is a “chance to change our history,” she told Reuters afterward. “I really decided I needed to run because I could see a pathway to winning.”

As the United States grapples with a deadly coronavirus pandemic that has disproportionately sickened and killed Black Americans and recent upheaval over police brutality, a record number of Black women are running for Congress.

Elliott is one of at least 122 Black or multi-racial Black women who filed to run for congressional seats in this year’s election; this figure has increased steadily since 2012, when it was 48, according to the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP).

As primary season draws to a close, nearly 60 Black women are still in the running, according to Collective PAC.

“People are becoming more comfortable with seeing different kinds of people in Congress. You don’t know what it looks like to have powerful Black women in Congress until you see powerful Black women in Congress,” said Pam Keith, a Navy veteran and attorney who is running in the Democratic primary for a Florida congressional seat.

Black women are nearly 8% of the U.S. population, but 4.3% of Congress, according to a report https://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/resources/black-women-politics-2019.pdf by the Center of Women and Politics and Higher Heights for America, a political action committee that seeks to elect more progressive Black women to elected office. They are underrepresented in statewide executive’s jobs and among mayors as well, according to the report.

But Black women voters showed the highest participation rate https://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/resources/genderdiff.pdf of any group in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.

Historically, Black women have been more likely https://www.brookings.edu/research/analysis-of-black-womens-electoral-strength-in-an-era-of-fractured-politics to win in majority-Black districts, but many are running this cycle in majority white or mixed districts, some of which had previously voted for Republicans.

“We’re going to flip this seat from red to blue,” said North Carolina’s Patricia Timmons-Goodson, the first Black judge to serve on the state Supreme Court and a former member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. “We have a candidate that knows and understands the district and its people,” said Timmons-Goodson, who is running for a seat in Congress.

Several of the eight Black women congressional candidates Reuters spoke to said they relate to voters better than their often wealthier opponents, because they, too, have lived through fiscal hardships.

“We almost lost our house a couple of times. We ran into financial difficulties when I was first starting my business,” said Jeannine Lee Lake, a former journalist who is running for Congress from Indiana against U.S. Vice President Mike Pence’s brother, Greg Pence, an incumbent business executive who reported https://disclosures-clerk.house.gov/public_disc/financial-pdfs/2017/10019708.pdf millions in assets last election cycle.

The coronavirus crisis has also highlighted the importance of issues these women are running on – improving healthcare, creating better jobs, ameliorating access to broadband internet.

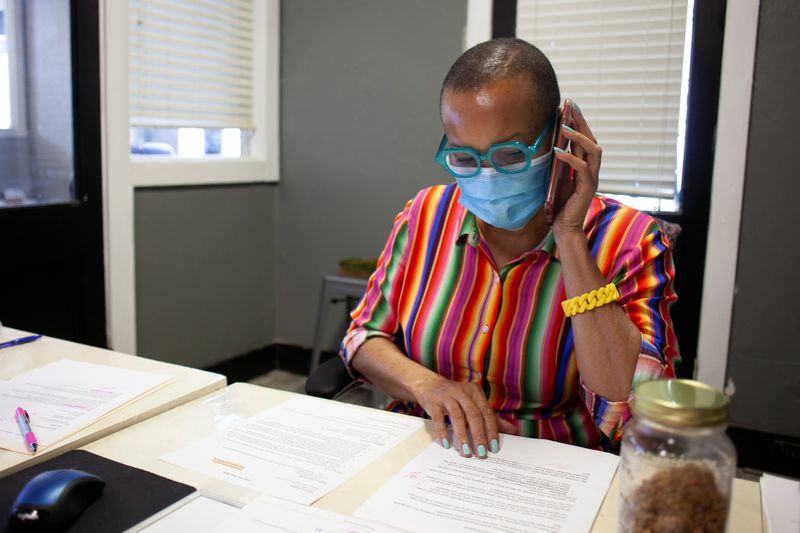

“It really has just amplified and co-signed what I was already talking about with voters,” such as the importance of agriculture and expanding Medicaid, said Alabama’s Adia McClellan-Winfrey, who holds a doctorate in psychology and is chair of the Talladega County Democratic Party.

Ohio candidate Desiree Tims returned home in 2019 after a stint in Washington, D.C., as a congressional aide and White House intern, intending to work at a law firm and pay down her student loan debt.

But she decided to run after watching people come together to bag clothes, share food and provide shelter following a rash of tornadoes that tore across the state, with little support from the federal government.

“After coming back from Washington, D.C., what I saw was the community doing the work, but their tax dollars not working for them,” Tims said.

Kimberly Walker, a veteran and former corrections officer from Florida running for Congress, says the solution to that discrepancy is clear.

“We need to have more people, average, everyday American citizens who are there fighting for average, everyday American citizens,” she said.

(Reporting by Makini Brice; Editing by Heather Timmons and Diane Craft)