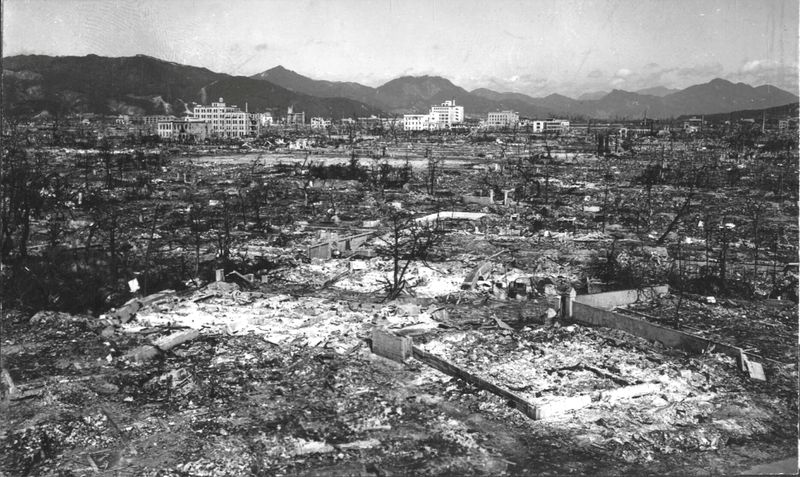

(Reuters) – The atomic bomb the United States dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945 killed tens of thousands and flattened the Japanese city in an instant.

“Little Boy,” as it was known, was the endpoint of years of research, wrangling a physics theory into a mechanism that would release the energy that binds together atoms.

The concept was simple: driving together enough uranium or plutonium at high enough speeds would create a “critical mass” so quickly that it would start an uncontrolled, nearly instantaneous chain reaction of neutrons knocking apart atomic nuclei.

(Click https://graphics.reuters.com/WW2-ANNIVERSARY/HIROSHIMA/rlgpdnqljpo/index.html to see an interactive graphic about developing atomic weapons.)

Each atom’s lost mass is converted to energy at a staggering exchange rate. Only 1.09kg of the 64kg of uranium in Little Boy became energy, but it was the equivalent of detonating 15,000 tons (13.6 million kg) of TNT, according to Los Alamos National Laboratory calculations.

About one square mile of Hiroshima was flattened, crushed by the hammer blow of Little Boy detonating about 580 metres (1,900 ft) overhead. Nearly everyone in that area died instantly. Farther away, the bomb’s heat ignited buildings and people, and deadly radiation bloomed.

Since World War Two, no country has attacked another with a nuclear weapon. But at least eight have developed them. More than 2,000 nuclear weapons have been detonated in experiments since 1945.

Thousands of nuclear weapons now sit in arsenals around the world, ready to deploy by aircraft or missile. The Arms Control Association estimates that there are nearly 14,000 such weapons, although of these only a third or so could be immediately used in a war.

Even so, 75 years have passed without a nuclear attack.

“I am hopeful that we can stretch the streak for decades more – but the real question is whether nuclear deterrence will work forever,” said Jeffrey Lewis, head of the East Asia Nonproliferation Project at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies.

“I am not so sure about that. And that means, sooner or later, our luck will run out.”

(Reporting by Simon Scarr, Marco Hernandez and Gerry Doyle; Editing by Karishma Singh and Clarence Fernandez)