“Lost River” is the debut effort by a new writer and director named Ryan Gosling. Maybe you’ve heard of him. He’s Canadian or something. We sat down with Gosling to discuss why the story of a young man and his mother (Iain De Caestecker and Christina Hendricks) trying to survive in the economic wasteland of Detroit spoke to him to strongly. What was it about this story that made it right for your directorial debut? When you were putting this project together, was there pressure to star in it yourself? RELATED:Ryan Gosling and Eva Mendes are totally pro-sweatpants Aside from Christina Hendricks and your partner, Eva Mendes, you’ve got a Brit, a Scot, an Irishwoman and an Australian playing Detroit residents. What do you have against American actors? What was the process of you for defining the visual language of this film? RELATED:Ryan Gosling doesn’t want to be the Sexiest Man Alive The drowned towns motif is such a striking visual. The image of him framed by street lamps particularly sticks out. How about the private sex-and-death club where Christina and Eva’s characters work? Where did that come from? Follow Ned Ehrbar on Twitter:@nedrick

I had written something when I was in my early 20s about child soldiers, and it was because I had gone to Uganda and Sudan and I had an experience that I wanted to elaborate on. I tried for a while to get that film made and I just couldn’t. I just wasn’t in a place in my career where I could make that happen. Then, you know, life happened and I was in in more films, and then suddenly I went to Detroit and I had a similar feeling where I just felt a real connection to the place and had an experience there that I wanted to share and elaborate on. Sometimes you read a script and you feel like you could contribute by acting, and then sometimes you have an experience where it’s, “If I don’t write this, no one will.”

It was definitely suggested that I be in the film, yeah. But my hat’s off to guys that are acting and directing in their own films. They’re making it look easy, and it’s not. It took everything I had just to direct this film, I can’t imagine being in it as well. This was all that I could do.

Landon [the toddler] is American, too! And he’s Marlon Brando reincarnated. (laughs) For the most part, I’d worked with everybody before and I just wanted to work with my friends on this film, and most of them I had seen a side of them that I hadn’t gotten to see in their work, and so I wanted to write for that. But then there was this central character of Bones (De Caestecker), which was obviously the most important piece and the hardest to find, but Ian was so much more than what I’d hoped for. He just has a quality of wanting to highlight everyone else that’s in the scene with him. He came [to Detroit] a month before hand and didn’t tell anybody, started stripping copper in these buildings, and he walked every block of these neighborhoods. He basically took Landon as a younger brother. He just brought this authenticity to it but just kept it in his pocket. He was never trying to show it. And this character in the film is a very selfless character who’s trying to protect and take care of his family in the best way he knows how, and Ian embodies all of that — in a real way, not in a way of, like, a performer, you know?

I had a year — not a solid year, by any stretch — but over the course of a year I took some trips to Detroit on my own and I was filming. And that really helped me — in one way because I felt like I was making the movie, even if it was just me, but that it had started and the train had left the station and now I had to finish. But it also helped me because now I had images that I knew were the film, not just inspiration for the film. I could show producers, actors, financiers, not “this is what it could be” but “this is what it is.”

I grew up next to a river where I had found a road leading into it, and that’s how I learned that they had sunken a bunch of towns to make this river. That’s sort of where that idea came from, but yeah, it’s a totally surreal, true thing that happens, and it’s very bizarre.

I was going for a more literal version of what I had seen, which was a road going down into the water, but then when it got down to it, it was such a low-budget movie that we couldn’t find one, we couldn’t afford to go where there was one and we couldn’t afford to make one. And so that’s when we just thought, “F— it, maybe lampposts will suggest it.”

It was based on the Grand Guignol and the Hell Cafe and the Death Cafe. All of these were part of a macabre entertainment scene in Paris in the early 1900s. A the Grand Guignol, they would put on these horror shows, murder theater where they would kill people on stage. It was fake but very realistic, and it gave birth to horror films. At that time, for whatever reason, there was this real macabre entertainment scene and fascination with death. We tried to root all the fantasy in this film in some form of reality, you know? So we used that as a big inspiration. But the idea was that in these sort of places — after a natural disaster or, in this case, an economic disaster — they attract people who have dark fantasies because they can enact them in these places where no one’s watching. You can get away in anything in these kinds of environments.

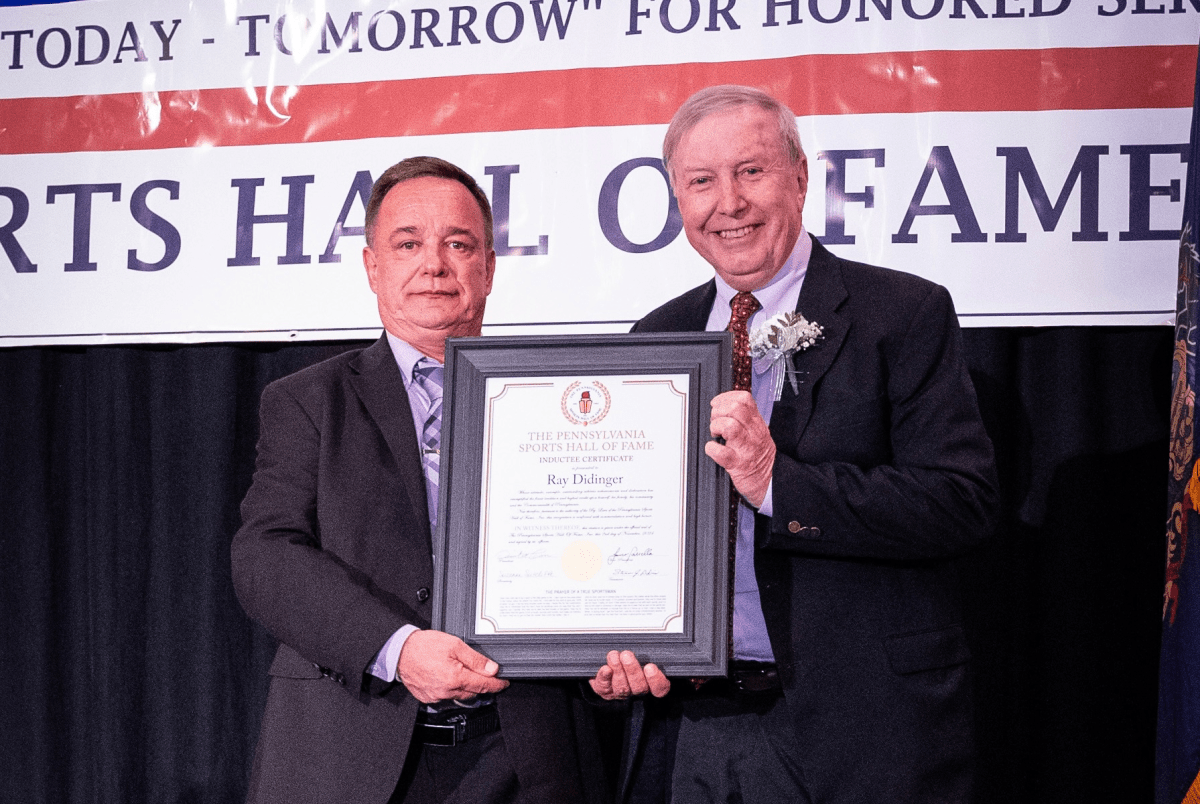

Ryan Gosling, director

WireImage