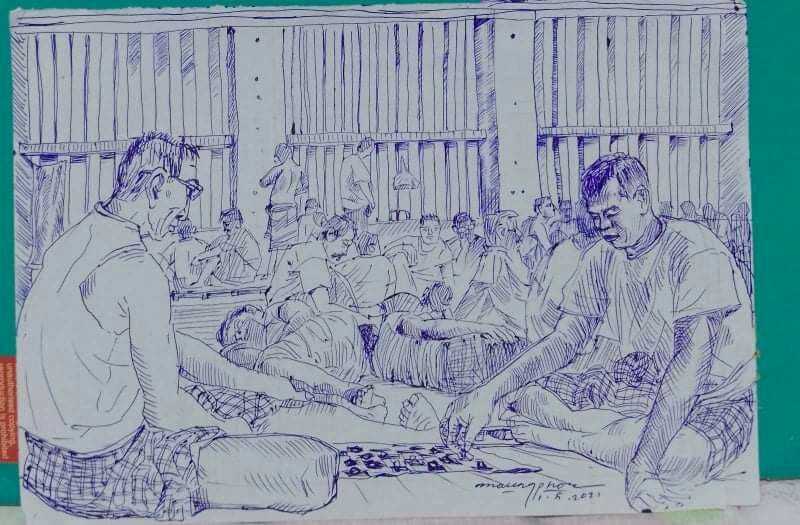

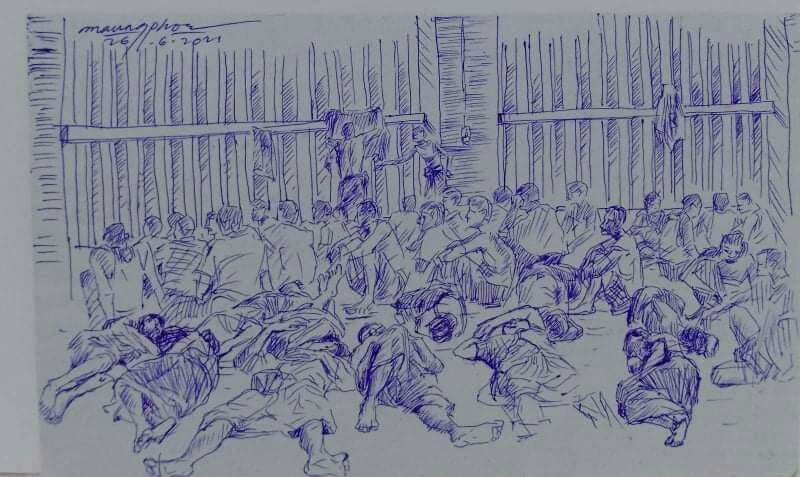

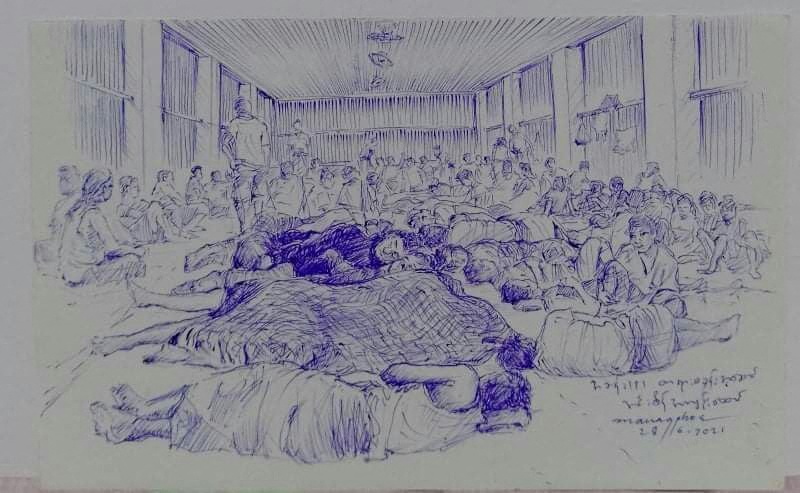

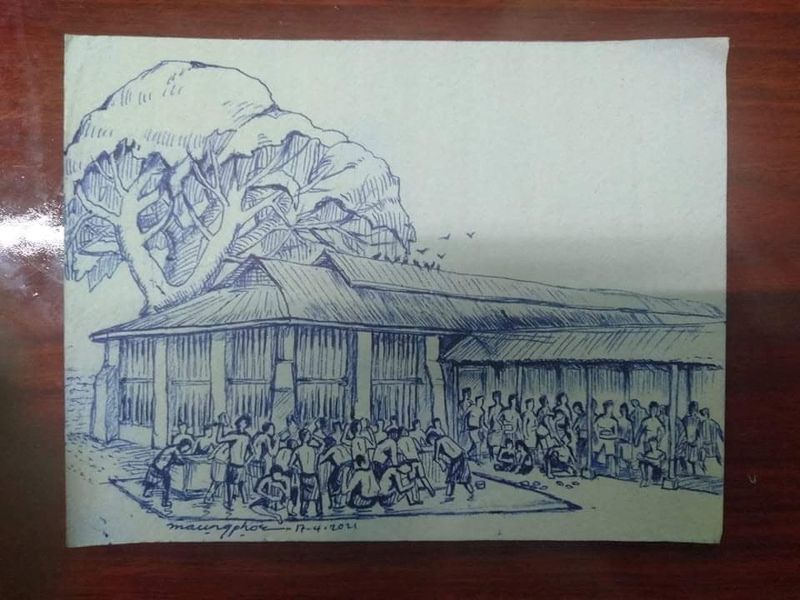

(Reuters) -In one drawing, dozens of men sit crammed into a single room, hunched with their knees together, every inch of space occupied. In another, they lie back to back on the floor, their faces straining with discomfort.

Fourteen sketches smuggled out of Myanmar’s Insein Prison and interviews with eight former prisoners offer a rare glimpse inside the country’s most notorious jail, where thousands of political prisoners have been sent since last year’s military coup and communication with the outside world is sharply limited.

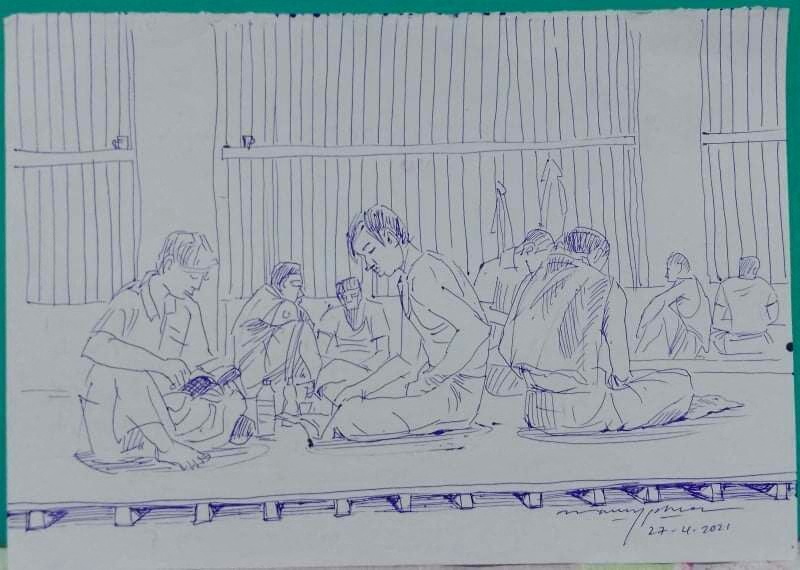

The rough, blue-ink sketches show daily life for groups of male prisoners in their dormitories, queuing for water from a trough to wash, talking or lying on the floor in the tropical heat.

Beyond those depictions, the eight recently released inmates told Reuters the colonial-era facility in Yangon is infested with rats, a place where bribes are common, prisoners pay for sleeping space on the floor and widespread illness goes untreated.

“We’re no longer humans behind bars,” said Nyi Nyi Htwe, 24, who smuggled the sketches out of the prison when he was released in October, after spending several months for a defamation conviction, on charges he denies, in connection with joining protests against the coup.

Reuters could not independently verify the accounts provided by the former inmates.

Myanmar’s junta, which seized power from the elected government of Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, and prison administration did not respond to multiple requests for comment on conditions shown in the sketches and described by the former inmates.

Humanitarian groups including the International Committee of the Red Cross told Reuters they have been denied access to the jail.

Built by the British in 1871, Insein is Myanmar’s largest prison, housing many people arrested for opposing the junta.

Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, convicted of breaking Myanmar’s Official Secrets Act in 2017, spent most of their 511 days behind bars in Insein. They were released in a 2019 amnesty, before the latest coup.

PRISON POPULATION SWELLS

The artist drew the prison sketches between April and July of last year. Later released, he declined to be interviewed or identified, telling Nyi Nyi Htwe he feared rearrest.

Nyi Nyi Htwe, who met the artist in prison, said he sketched prisoners if asked and drew prison scenes wherever he went, saying he felt more relaxed while drawing. He gave Nyi Nyi Htwe the sketches as a birthday present.

Nyi Nyi Htwe said he smuggled them out on his release to show friends, family and others the conditions inside.

Since the coup, 10,072 people have been detained in the Southeast Asian country, including Suu Kyi and most of her cabinet, and over 1,730 people have been killed, according to the nonprofit Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, whose tallies are widely cited. The junta has said AAPP’s figures are exaggerated.

Many of those detained have been sent to Insein.

Built to incarcerate around 5,000 people, the prison has seen inmate numbers swell to over 10,000 since the coup, said a spokesperson for the AAPP. Reuters could not confirm the figures.

The sketches reflect the increase in the months after the coup, said Nyi Nyi Htwe.

In one from late April, a few prisoners sit apart in their dorm, some reading books. A picture from June shows about 60 people in the same room – many lying in tight rows down the centre, the rest hunched against the walls.

Nyi Nyi Htwe said he and as many as 100 others were packed well beyond capacity into a room where they “slept a finger-width apart,” and that he watched prison officers beat inmates with batons and had to pay bribes to send messages to family that they told him often did not arrive.

‘LUCKY NOT TO DIE’

With the overcrowding came water shortages, disease, fatigue, fighting between prisoners and flourishing bribery, said people released in recent months.

“Rats ran around in the room. The toilets were filthy. The food was mixed with flies. Those who couldn’t pay a bribe had to sleep next to the toilet bucket,” said Sandar Win, a 42-year-old social worker jailed at Insein for several months for defamation after protesting against the junta.

She was released under an amnesty while awaiting sentencing for the charges, which she denies. She has since fled Myanmar.

Access to outdoor latrines was limited, forcing prisoners to defecate in buckets in their rooms, three women former inmates said. These unsanitary conditions allowed skin and bowel diseases to spread, and there was little medical help, they said.

A handwritten note by a group of anonymous Insein inmates, smuggled out to a prominent human rights activist in February, alleges several instances of medical negligence, including failure to treat people beaten unconscious and a person who had suffered a stroke and was paralysed.

“These cases are happening right in front of us,” said the note, which was shown to Reuters by the activist, Nan Lin. “We request urgent help from international organisations and local organisations.”

Reuters could not independently verify the note’s authenticity, but several former inmates said they had witnessed or suffered beatings by guards and there was little medical support.

Despite a COVID-19 vaccination drive at Insein last summer that was publicised on state media, former inmates said the coronavirus thrived in the crowded prison. At least 10 prisoners are suspected to have died from the disease, according to the AAPP.

Nyi Nyi Htwe, who has joined an armed rebel group, said nearly two-thirds of his dormitory were sick with COVID symptoms last summer.

“They put all the sick people in our room — high fever, coughing and ill,” he said. “I was lucky enough not to die.”

A set of smuggled notes shown to Reuters by an aid group show an exchange between a father, held on defamation charges, and his young son.

“Behaving well, Papa. I miss you. I’d like to have a toy boat,” wrote the boy.

“My little son,” came the reply, including a tiny boat the father fashioned from instant coffee wrappers. “I love you so much, my sweetheart. Please listen to your grandma.”

(Reporting by Reuters Staff. Writing by Poppy McPherson and John Geddie; Editing by William Mallard)