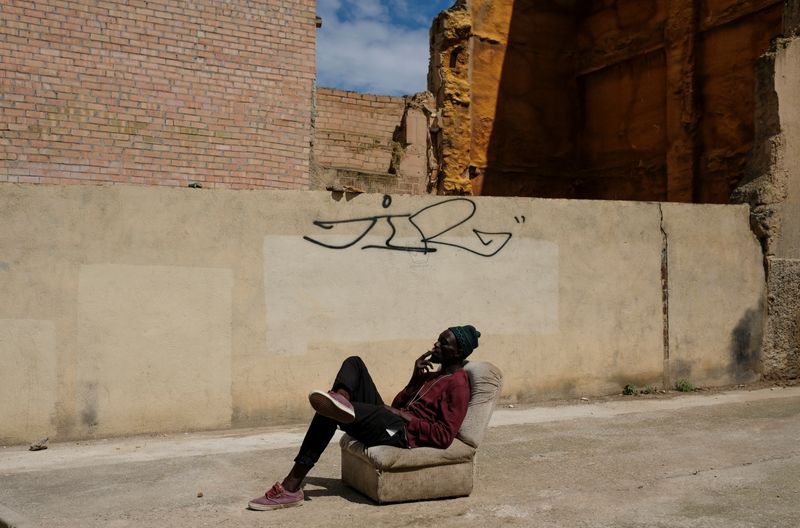

LLEIDA, Spain (Reuters) – Like many African immigrants seeking fruit-picking jobs in Spain, Europe’s largest fruit and vegetable exporter, Ibrahim Ndoye had to sleep rough on the streets of Lleida for 10 days this month as nobody would rent him a room.

The 42-year-old Senegalese acknowledges that restrictions over the coronavirus and fears of the disease may have undermined the northeastern town’s hospitality while stoking demand for seasonal jobs, but he largely blames racism.

It took the intervention of a Black celebrity, and momentum from the Black Lives Matter protests, to change Ndoye’s fortunes, temporarily. He is now one of 80 immigrants staying at two hotels in Lleida paid for by Monaco soccer player Keita Balde, 25.

“What he has done is something huge and human,” said Ndoye, who has lived in Spain for 19 years and travelled to Lleida after losing a restaurant job on the coast due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Local councillor for civil rights Sandra Castrol said Lleida saw a huge early inflow of seasonal job seekers this year, before the campaign starts in earnest in July, after many lost jobs in the tourism sector or as street vendors as a result of the pandemic.

Balde’s gesture has grabbed media attention, putting the spotlight on the long-standing struggles of the thousands of seasonal farm workers across Spain.

AFRAID TO SPEAK OUT

In late May, after learning about their plight, Balde, who was born in Spain to Senegalese parents, offered to pay for the harvest-season hotel accommodation of around 200 migrants.

Most hotels initially rejected the offer, said Nogay Ndiaye, a Catalan-Senegalese activist who represented Balde in the talks. “There’s been racism by the hotels,” she said.

The local hotel federation denied the accusation, citing hotel closures due to the coronavirus, repairs and administrative issues.

“If one person wants to rent 20 or 25 rooms … if you are being offered to get paid in advance and you reject it because they are Black people, how do you call that?” said Ndiaye.

Rights group SOS Racismo tweeted earlier this month that the homeless migrants in Lleida showed: “The state, all its institutions and our economic system maintains a racial and unequal system”.

After about two weeks, municipal authorities and the hotel federation helped arrange a two-week hotel stay paid for by Balde, while another 120 people are staying in a municipal pavilion.

But dozens more Black men were earlier this week sleeping in Lleida’s crammed covered square full of mattresses and suitcases.

In a June 1 video, Balde said he was not looking to stir tensions, but “looking for a solution … No-one deserves this indifference and difficulties”.

The situation is not confined to the city of 139,000 where around 25,000 migrants come for the season, or the northeast.

In February, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty Philip Alston cited a migrant settlement in the southern province of Huelva, which houses up to 2,000 people during the peak strawberry picking season, where he said conditions were “inhuman”, without adequate sanitation or access to water.

By law, farmers can hire only legal immigrants and have to provide housing. But many undocumented migrants arrive anyway and often get underpaid jobs without lodging, even though most of the sector complies with the law, Castrol said.

She called for the regularization of the city’s undocumented migrants to prevent labour exploitation and vowed to seek a permanent lodging solution after years of neglect.

But even legal immigrants like Ndoye say they are afraid to defend their rights: “I am not going to risk losing a job,” he said.

(Reporting by Joan Faus, Nacho Doce and Luis Felipe Castilleja, additional reporting by Julien Pretot; Writing by Joan Faus; Editing by Andrei Khalip and Janet Lawrence)