SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) – A few weeks after San Francisco’s school district moved to remote learning last year in hopes of halting the spread of the coronavirus, Kate Sullivan Morgan noticed her 11-year-old son was barely eating. He would spend days in bed staring at the ceiling.

The mother formed a pod with three other families so the students could log on to their online classes together. That helped, but her eldest remained withdrawn and showed little interest in his hobbies, such as playing piano and drawing. Then her younger son, then 8, started to spiral down.

“He would scream and cry multiple times per hour on Zoom,” she said. “It was all really scary and not in keeping with his personality.” She scaled back her job as a healthcare regulatory attorney to be there for her sons.

In December, with schools in San Francisco still closed, the family packed up and moved more than 1,700 miles, to Austin, Texas, so the children could attend school in person. “Kids are resilient, but there is a breaking point,” Sullivan Morgan said.

With schools nationwide locked down amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental health consequences on students have come into a sharp focus.

Reuters surveyed school districts nationwide in February to assess the mental health impacts of full or partial school shutdowns. The districts, large and small, rural and urban, serve more than 2.2 million students across the United States.

Of the 74 districts that responded, 74% reported multiple indicators of increased mental health stresses among students. More than half reported rises in mental health referrals and counseling.

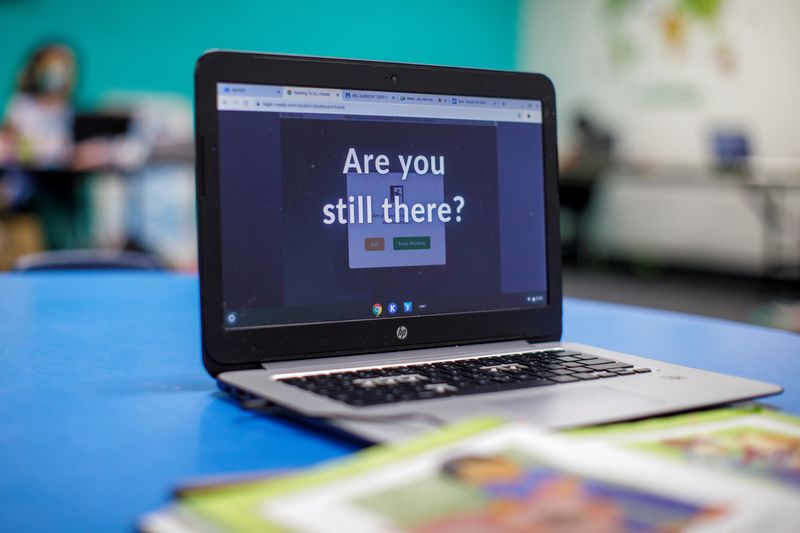

Nearly 90% of responding districts cited higher rates of absenteeism or disengagement, metrics commonly used to gauge student emotional health. The lack of in person education was a driver of these warning signs of trouble, more than half of districts said.

The stresses didn’t affect only students: 57% of responding districts reported an increase in teachers and support staff seeking assistance.

School closures have affected districts in every state. In the spring of 2020, all U.S. K-12 public schools closed, at least temporarily, to help slow the spread of COVID-19. As of February, 57% of students attended public schools that were completely or partially closed, according to Burbio, a service that tracks school openings.

Some school boards, teachers union leaders and parents still advocate full or partial school closures to protect the health of children or to prevent community spread. Yet research over the last year has shown that public schools that follow social distancing guidelines typically experience low rates of spreading COVID.

“Though outbreaks do occur in school settings, multiple studies have shown that transmission within school settings is typically lower than – or at least similar to – levels of community transmission, when mitigation strategies are in place in schools,” said a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report. “The majority of cases that are acquired in the community and are brought into a school setting result in limited spread inside schools, if comprehensive mitigation strategies are in place.”

Severe cases among children comprise less than one tenth of one percent of all deaths, the CDC said. Of the 36,860 overall child deaths over the last year, 216, about a half percent, involved COVID-19.

In Rhode Island, virtual students were more likely to test positive for COVID than students attending in-person, state education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green told researchers and doctors in January. “It’s really important to have data,” Infante-Green said. “Most of the cases we’ve seen have been outside of school.”

Dimitri Christakis, director of the Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, said the Reuters survey affirms concerns he has had since schools stuck with remote learning.

“We’ve done our children a tremendous disservice,” Christakis said.

As students stay sheltered in their homes, away from friends and teachers, other COVID-related factors can cause the stresses to cascade. The anxiety from seeing a parent lose work. The death or illness of a family member from the disease.

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

More than a dozen school district leaders told Reuters of students suffering silently with depression, eating disorders, neglect and emotional, physical or sexual abuse. Were students in a school setting, these warning triggers would be more easily noticed, they say.

In California, Joel Cisneros, director of school mental health for the Los Angeles Unified School District, worries about those who fall through the cracks.

“The most concerning thing would be when students or parents or caregivers try to weather this by themselves,” Cisneros said. “That they try to grab the stressors that they may be faced with, and do not ask for help.”

Such fears are shared in the North Thurston Public Schools in Washington State, where most of the 14,000 students didn’t step foot in a school building for nearly a year. The lack of on site schooling has made it daunting for district mental health and social services staff to reach children needing help. The district has 11 mental health specialists who provide one-on-one counseling and social services to students and their families.

“When we had students in person, it was much easier” to monitor the kids, said Mandy Garrison, a licensed clinical social worker who is one of the specialists. With schools closed, she said, several “typically well functioning” pupils suddenly began “struggling with the social isolation, anxiety, fear of the future and depression.”

The district has struggled to locate some of the hundreds of students who have disappeared from school despite repeated attempts to contact those families by phone, email or with home visits. Since the beginning of the pandemic, overall district enrollment fell from 14,800 in March 2020 to less than 13,990 in March 2021.

“They are disappearing,” said Leslie Van Leishout, director of student support. “We can’t help them or their mental health needs if we can’t find them.”

URGING STUDENTS BACK

In the Somerset Independent School District south of San Antonio, Texas, schools reopened in September. Still, one-in-five students in a district primarily serving minority children have opted for virtual education, said Superintendent Saul Hinojosa.

The district has seen the number of suicide assessments double this school year; when staff learn of a student exhibiting potentially suicidal behaviors, they typically alert a team of mental health professionals to assess the child. Absenteeism and disengagement increased “exponentially” and mental health referrals doubled, Hinojosa said. These increases are concentrated among the students studying virtually, 75% of whom are failing, the district said.

The district is urging students to come back. “We’re having these conversations with parents and telling them it’s OK to bring them to school, it’s safe,” Hinojosa said.

Aided by Community Labs, a San Antonio nonprofit, the district launched a $2 million program to test some 85% of its 2,166 staff and students weekly for COVID. About half a percent tested positive each week. The 10 or fewer who did likely became infected outside school, the district said.

Some parents remain uncomfortable sending their children back to school, and they say for good reason.

Mary Villanueva, whose husband has diabetes and lung damage from a previous bout of pneumonia, said the risk still seems too high. She has kept her 14-year-old daughter and 7-year-old twin grandchildren home since last March. She said they were generally coping well, though the pandemic has exacerbated her grandson’s anxiety issues. “He won’t wear a mask. He gets claustrophobic and will have an anxiety attack,” she said.

Terry White, an American history teacher at Somerset High, kept his freshman son in virtual education this fall because his wife suffers from an autoimmune disease that puts her at high risk from COVID-19. After missing football and months without interaction outside home, their son lost interest in classes and became withdrawn.

After several weeks of testing and contact tracing showed COVID was not spreading in schools, the Whites sent him back to class. “We have our old son back, laughing and joking,” White said.

Long before COVID, the Modoc Joint Unified School District in northeastern California struggled with a faltering economy, substance abuse and child neglect, said superintendent Tom O’Malley, a life-long resident.

Then the schools closed. When they did, Modoc’s Child Protective Services unit saw a 30% decrease in child abuse reports.

O’Malley worried about abuse happening behind closed doors. A month after school started in September, students started to open up to staff about emotional, physical or sexual abuse they reported experiencing during the lockdown.

In a three-week span last fall, the staff intervened in 12 cases of potentially suicidal students, up from the one to two students they normally see in a year. In each case, school staff assessed whether they needed to contact police or find other resources to help the families with food, clothing or medical and mental health care.

“We were overwhelmed,” O’Malley said.

Without the regular oversight from school and with parents working or grappling with their own anxieties, many students are on their own. That can be a recipe for trouble.

Since classes went virtual last year, Jayme Banks, deputy chief of prevention, intervention and trauma at the Philadelphia Public School District, has received a report almost every week from police about students, including shootings, car accidents and arrests. Fatal youth shootings in the city rose from 55 in 2019 to 87 in 2020, and nonfatal shootings increased 72% over the previous four year average, from 309 to 534, according to data from the Philadelphia Office of the Comptroller. Were the students in schools, some educators believe, fewer cases would occur.

With each situation, the district works with teachers and counselors to help the student get back on track in classes and find therapy and community programs.

Helping students navigate such traumatic experiences can weigh on teachers. “It’s a heavy lift,” Banks said.

For others, the daily struggle of virtual education and working with students who are slipping away becomes too much.

Banks’ staff is reaching out to educators who seem overwhelmed and helping them connect with therapists and other support systems. In one case, Banks said, she and her team intervened to help a teacher thought by colleagues to be suicidal.

SHORT TERM, LONG TERM

At the dawn of the pandemic, school closings initially received little pushback; parents assumed the shutdowns would last a few short weeks. A full year later, some parents are becoming increasingly vocal.

Siva Raj, a single father of two boys in San Francisco, is co-leading a campaign to recall the district’s school board. His older son, 14, has lost all motivation to learn, he said, and often just goes between his bed and computer and back.

“It’s been shattering to see that,” Raj said. “I feel like I am failing him.”

When children do return to the classroom, some parents say they see a change.

In San Francisco, as her children struggled with remote learning, Sullivan Morgan and her husband pored over their finances. They saw there was no way they could afford private schools, which offered in-person teaching, for both boys.

In the fall, they decided to sell their house and move to Austin, where their sons could attend public school. Since January, both sons have been back in school five days a week. Her oldest is playing piano again.

“They are back to their old selves,” the mother said.

(Reporting by Benjamin Lesser, M.B. Pell and Kristina Cooke. Editing by Ronnie Greene)