(Reuters) – When the head of the World Health Organization returned from a whirlwind trip to Beijing in late January, he wanted to praise China’s leadership publicly for its initial response to the new coronavirus. Several advisers suggested he tone the message down, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

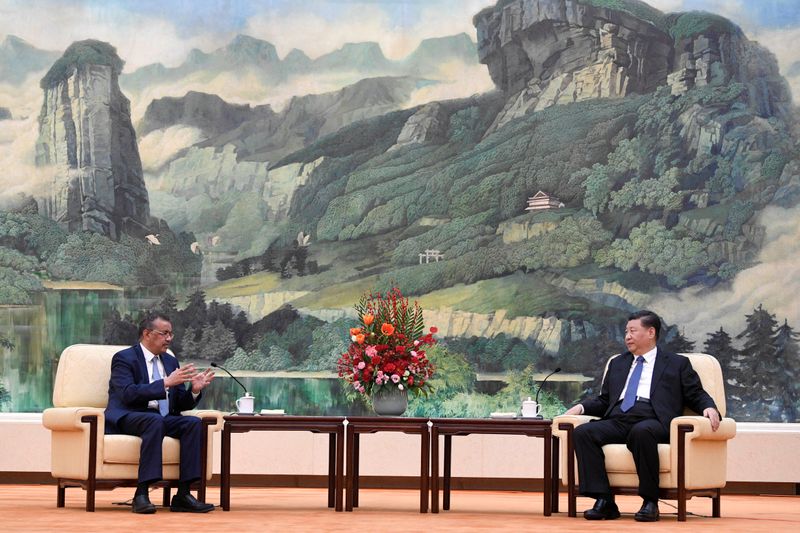

After meetings with President Xi Jinping and Chinese ministers, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was impressed by their knowledge of the new flu-like virus and their efforts to contain the disease, which by then had killed scores in China and started to spread to other countries.

The advisers encouraged Tedros to use less effusive language out of concern about how he would be perceived externally, the person familiar with the discussions said, but the director general was adamant, in part because he wanted to ensure China’s cooperation in fighting the outbreak.

“We knew how it was going to look, and he can sometimes be a bit naive about that,” the person said. “But he’s also stubborn.”

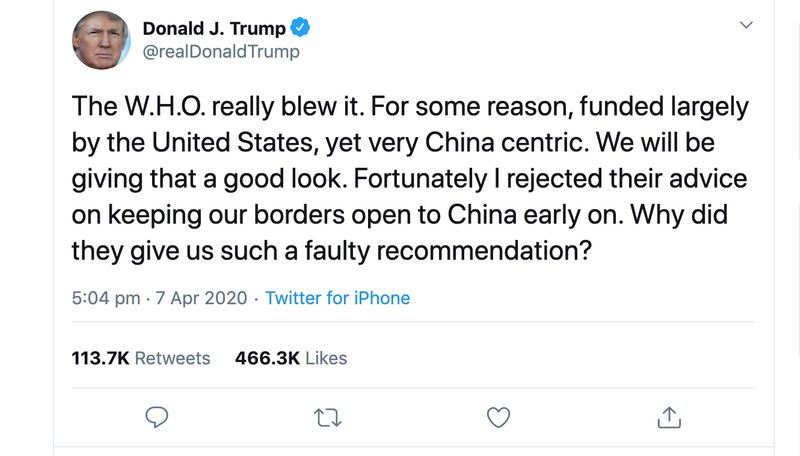

The WHO chief’s subsequent lavish public praise of China’s leadership for its efforts to combat the disease came even as evidence mounted that Chinese officials had silenced whistleblowers and suppressed information about the outbreak. His remarks prompted criticism from some member states for being over the top. U.S. President Donald Trump has led the charge, accusing the WHO of being “China-centric” and suspending American funding of the health agency.

The internal debate over the WHO’s messaging around China provides a window into the challenges facing the 72-year-old United Nations organization and its leader as they engage in battles on two key fronts: managing a deadly pandemic and coping with hostility from the United States, its largest donor.

Interviews with WHO insiders and diplomats reveal that the U.S. offensive has shaken Tedros at an already difficult time for the agency as it seeks to coordinate a global response to the pandemic. COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, has killed more than 300,000 people and continues to spread. The virus is thought to have emerged in a market in Wuhan, China, that sells live animals.

Tedros is “obviously frustrated” by Trump’s move and feels the WHO is being used as a “political football,” the person familiar with the discussions said.

“We’re in the middle of the fight of our lives – all of us around the world,” said Michael Ryan, the agency’s top emergencies expert, about the challenges facing the WHO. In an interview with Reuters, Ryan said the WHO is focused on helping health systems to cope, developing vaccines and drugs, and getting economies back on track.

“That’s a big enough task to worry about for any organization,” said Ryan. “I’ve got to now deal with the potential that we’ll have a significant disruption in funding in front-line essential health services in many fragile countries in the coming months.”

“It’s bending the system,” added Ryan, an Irish doctor and epidemiologist, “but it’s not breaking it.”

The WHO said Tedros was not available for an interview. He has strongly rejected criticism that he was too quick to praise Beijing, saying China’s drastic measures slowed the virus’ spread and allowed other countries to prepare their testing kits, emergency wards and health systems. He has also said he hoped the Trump administration would reconsider its freeze, but that his main focus is on tackling the pandemic and saving lives.

Tedros knew there was a risk of upsetting China’s political rivals with his visit and his public show of support, according to the person familiar with the discussions — an account backed by a WHO official. But the agency chief saw a greater risk – in global health terms – of losing Beijing’s cooperation as the new coronavirus spread beyond its borders, the two sources said.

“That’s the calculation you make,” said the person familiar with the discussions.

During the two-day Beijing visit, Tedros secured agreement from China’s leadership to allow WHO experts and a team of international scientists to travel to China to investigate the origins of the outbreak and find out more about the virus and the disease it was causing. That delegation included two Americans.

Ryan, who accompanied the WHO chief on the trip, said he and Tedros both thought it was important to support China once they became aware of its containment plans and found them solid. The WHO’s aim was to ensure the response was implemented “as aggressively, as fast and as successfully as possible.” He added: “You want to ensure that that commitment to doing that is absolute and you want to ensure that you keep the lines of communication open if there are problems with that implementation.”

The WHO, in a follow-up statement, said it expressed appreciation to China “because they cooperated on issues we had sought support on,” including isolating the virus and sharing its genetic sequence, which enabled other countries to develop tests. At a meeting of the WHO’s executive board in early February, the agency said, “most countries overwhelmingly praised China for its response to this unprecedented outbreak.”

The Trump administration, which has come under fire at home for its own handling of the outbreak, isn’t easing off its recent attacks on the WHO and China.

A senior U.S. administration official told Reuters the WHO “repeatedly failed to acknowledge the growing threat of COVID-19 and China’s role in the spread of the virus.” Noting that the United States has been a larger contributor to the WHO than China, the official said the WHO’s actions were “dangerous and irresponsible” and had contributed to the public health crisis “rather than aggressively addressing it.”

The U.S. official alleged that “poor coordination, lack of transparency, and dysfunctional leadership have plagued its response” to the threat of COVID-19, among other health crises. “It’s time for the United States to stop giving millions of dollars to an organization that does more to impede global health than to advance it.”

China – whose combined contributions to the WHO’s current two-year budget were due to be about a third of what the United States was expected to pay – has stood by the WHO chief.

“Since the outbreak of COVID-19, WHO, under the leadership of director general Tedros, has been actively fulfilling its responsibilities and upholding an objective, scientific and impartial position,” China’s foreign ministry said in a statement to Reuters. “We pay tribute to the professionalism and spirit of the WHO and will continue to firmly support the WHO’s central role in global cooperation against the pandemic.”

China also rejected American criticism of its response to COVID-19. Beijing has been “open, transparent and responsible” in sharing information about the virus, the foreign ministry said. It added Beijing had maintained close communication and cooperation with the WHO, and it “appreciates” the positive comments the agency has made about China’s response to the outbreak.

China’s State Council, or cabinet, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“GRINDING OF TEETH”

The WHO has come under fire before. Its 2009 declaration of the H1N1 flu outbreak as a pandemic later drew criticism from some governments that it triggered countries to take expensive measures against a disease that ultimately turned out to be milder than originally thought. The agency and its then-director general Margaret Chan also faced sharp criticism for not reacting fast enough to the deadly Ebola outbreak in West Africa that began in December 2013.

Chan has defended her decision to declare the H1N1 flu outbreak a pandemic but admitted that the WHO was “overwhelmed” by the Ebola outbreak, which she has said “shook this organization to its core.”

As COVID-19 has spread, 55-year-old Tedros has become the public face of the global fight against it, holding near-daily news conferences, calling heads of state when the virus reaches their doorstep to offer support, and tweeting frequently to his 1.1 million followers. He teamed up with pop music superstar Lady Gaga to organize a benefit concert for health workers that was broadcast online last month.

The son of a soldier, Tedros was born in Asmara, which became the capital of Eritrea after independence from Ethiopia in 1991. Tedros lost his younger brother to a childhood disease that the WHO said was suspected to be measles. A microbiologist by training, Tedros served as Ethiopia’s minister of health and then foreign minister.

In 2017, Tedros became the first African to lead the WHO, winning the top job despite potentially damaging questions surfacing late in the race about whether he had any role in restricting human rights or covering up cholera outbreaks in Ethiopia. He denied the accusations, as did Ethiopia.

As head of the global health agency, which has offices in 150 countries and 7,000 staff, he has drawn praise from world health experts and senior colleagues for implementing fundamental changes at the WHO, including re-establishing the emergency-response department that Ryan now heads.

When a disease breaks out, Tedros is often quick to visit the epicenter in person. He made at least 10 trips to the Democratic Republic of Congo during a nearly two-year Ebola epidemic that erupted in August 2018. That outbreak had been close to being halted before resurging last month.

A Western diplomat recalled having witnessed Tedros cry after a Cameroonian doctor working for the WHO was shot dead at an Ebola hospital in Congo in April 2019. “I’ve seen that passionate style. He takes things personally,” the diplomat said.

China informed the WHO on Dec. 31, 2019, of a concerning cluster of pneumonia cases. On Jan. 14, the WHO said in a tweet that preliminary investigations by Chinese authorities had found “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” That statement would later be cited by Trump as a sign the agency wasn’t being skeptical enough toward China. The same day, a WHO expert said it was possible there was limited transmission occurring. On Jan. 22, a WHO mission to China said there was evidence of human-to-human transmission in Wuhan but more investigation was needed to understand the full extent.

In late January, Tedros and three colleagues flew to Beijing. “I think we got the official invitation at 7:30 in the morning and we were on the airplane at 8:00 p.m.,” said Ryan.

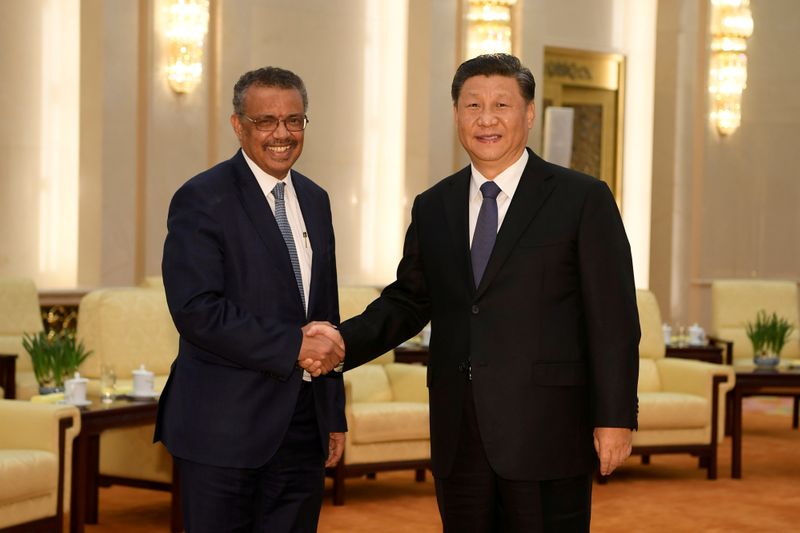

During the Jan. 28 meeting with China’s president, the WHO chief discussed the sharing of data and biological material, among other collaboration. Tedros tweeted a photo of himself and Xi shaking hands, saying they’d had “frank talks” and that Xi had “taken charge of a monumental national response.”

At a press conference the following day in Geneva, Tedros praised Xi’s leadership, saying he was “very encouraged and impressed by the president’s detailed knowledge of the outbreak.” The WHO chief added that China was “completely committed to transparency, both internally and externally.”

By contrast, during the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS, in 2003, the WHO chief at the time, Gro Harlem Brundtland, was openly critical of China when it was slow to report and share information about the emerging epidemic.

“Tedros has a different approach” than Brundtland, another WHO official said. “It took a lot of phone calls and patience.”

Brundtland, in a written response to Reuters, said she spoke out publicly because China hadn’t provided access to the WHO. “This time was different,” she said, without elaborating.

Publicly criticizing governments can make them reluctant to share information about disease outbreaks or otherwise cooperate, WHO veterans say. Michel Yao, head of emergency operations for WHO’s Africa region, said he had seen some nations shut down access to the WHO when they felt under pressure. This happened on several occasions when the WHO announced cholera outbreaks in Africa, Yao told Reuters, without naming the countries. “You lose access to data, and you lose access to capacity to at least assess the risk of the particular disease.”

But Tedros’ warm words for Beijing grated on some. “When he refers to China with praise, there is always a grinding of teeth,” one European envoy who attends Tedros’ weekly briefings for diplomats of member states told Reuters.

DEATH THREATS

The World Health Organization has limited leverage over member states. It has no legal right to enter countries without their permission, nor does it have any power of enforcement. So, the main tools at Tedros’ disposal are politicking and cajoling its 194 member states into abiding by the International Health Regulations framework they agreed to in 2005.

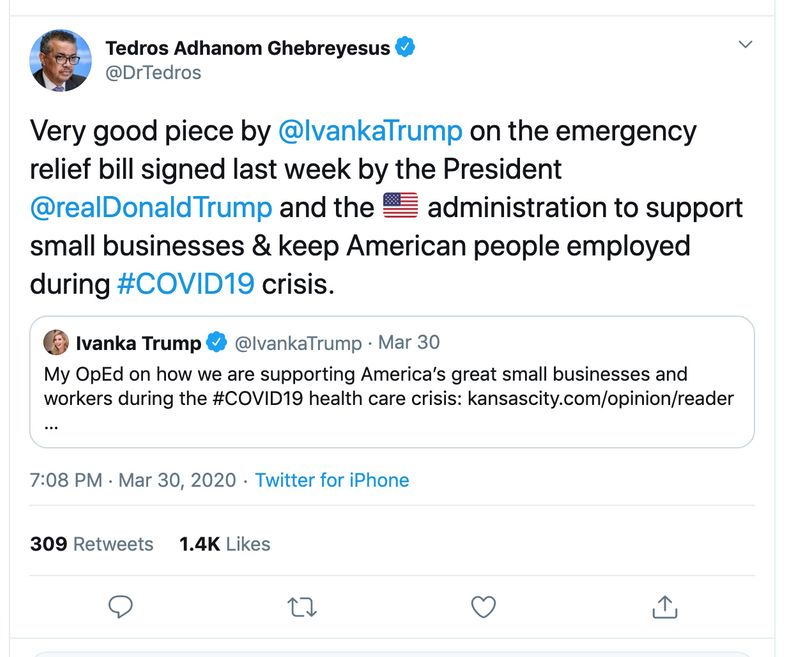

Tedros has praised a number of governments battling the new coronavirus, including Korea, Italy, Iran and Japan. On March 30, he publicly complimented Trump’s daughter and presidential adviser, Ivanka Trump, for an article she wrote about the U.S emergency relief bill, tweeting, “very good piece.”

Among WHO insiders, the perception in March was that relations with the United States were “good,” said the first WHO official. Ryan said in the interview that communications between the WHO and Washington in early 2020 were part of the “normal bump and grind of multilateral organizations.” He added: “I certainly for my part did not perceive that there was a major, major issue brewing.”

During a March 23 call, Tedros and Trump had a “good and cordial” discussion regarding the COVID-19 response and “nothing was raised on the funding issue,” the WHO said in its statement.

Trump initially voiced repeated praise of China and its president for their response to the crisis. By mid-March, he was ramping up his criticism of Beijing’s handling of the virus, saying Beijing should have acted faster to warn the world. His own administration’s response to the pandemic was coming under wide criticism at the time, including its troubled effort to roll out tests for the disease. Trump, who staunchly defends his performance, faces a re-election campaign as the coronavirus has claimed tens of thousands of American lives and ravaged the U.S. economy.

At the same time, the United States and other countries had been pressing WHO’s leadership for several months to make stronger statements about the need for transparency and the timely sharing of accurate information by member states, “and those concerns were not acted upon by the WHO,” a Western diplomatic source said.

Andrew Bremberg, U.S. ambassador to the U.N. in Geneva and a former White House official, had met regularly with Tedros to discuss the WHO’s response and voice concerns, two European envoys said.

The WHO, in its statement, said Tedros asks all countries to share information under the international regulations that member states have agreed to.

On April 7, Trump threatened to withhold WHO funding, criticizing the agency for being too close to China and too slow to alert the world to the epidemic, an accusation the agency strongly rejects. The threat had teeth, as Washington is the WHO’s largest funder. For the current two-year period, ending in December 2021, it was due to contribute $553 million in combined membership fees and voluntary contributions, or 9% of the agency’s approved budget of $5.8 billion, according to the WHO. That’s nearly three times China’s $187.5 million share, WHO figures show.

Tedros appeared rattled the following day during a regular news conference, at one point disclosing he had been the target of “racist” comments and even death threats, and gave long, impassioned responses to questions from reporters.

In a 12-minute reply to a question about Trump’s criticisms of the WHO and his funding-cut threat, Tedros called for unity, adding, “we will have many body bags in front of us if we don’t behave.” In response to accusations that the WHO was too close to China, he replied, “we’re close to every nation.”

The WHO, in its statement, said Tedros was calm and measured during the news conference and that he said the U.S. decision was regrettable. During his three years in office, Trump has criticized other multinational organizations and withdrawn funding from other U.N. agencies.

Trump announced the funding freeze a week later. Countries typically contribute to the WHO through membership dues and voluntary contributions. A second senior U.S. administration official said Washington already has paid almost half of the $122 million of the membership dues it owed for 2020. The official added that Trump’s freeze means Washington will likely redirect the remaining $65 million in dues payments and more than $300 million in planned giving to other international organizations.

Two Western diplomats said the U.S. funding suspension is more harmful politically to the WHO than to the agency’s current programmes, which are funded for now. But they also voiced concern that the freeze could have long-term impact, especially on central programmes such as those targeting polio, AIDS and immunization that are supported by Washington’s contributions.

“It has been a big blow to WHO and to Tedros,” said the second WHO official.

Tedros, asked about relations with the United States, told reporters on May 1: “We are actually in constant contact and we work together.” A WHO spokeswoman said dialogue and technical collaboration continue between the agency and Washington. The U.S. mission to the U.N. in Geneva declined comment.

“SHOT IN THE ARM”

Trump isn’t the only one prodding the WHO. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has called for an independent review of the outbreak and the WHO’s response. The European Union has proposed a resolution calling for a timely evaluation of the pandemic response, including by the WHO, an idea that’s due to be considered at the WHO’s annual assembly of ministers next week.

The WHO said Tedros has promised to conduct a post-pandemic review of the agency’s performance, including by the WHO’s independent oversight body, which is standard practice after a health crisis.

But so far, most major donors have closed ranks around the WHO. France, Germany and Britain have voiced support for the agency, saying now is the time to focus on fighting the outbreak rather than apportion blame. A German government official described the U.S. approach of focusing on past events rather than joining the fight against the outbreak as “absurd.” French President Emmanuel Macron is supportive of the WHO because he believes it is essential to an effective response to the crisis, one of his advisers said.

China’s foreign ministry, in its statement, said that Beijing is supportive of the WHO director general setting up a review committee to evaluate the global response to COVID-19 “at an appropriate time after the pandemic is over.” It added it objects to the eagerness of some countries to start reviewing the WHO and trace the origins of the virus, which it said were attempts to “politicize the epidemic” and interfere with the WHO’s work.

WHO insiders saw a victory of sorts in a webcast launch of an agency initiative on April 24 that turned into a public show of support for the organization and its leader. During the event, which was on the topic of accelerating the development of tests, drugs and vaccines against COVID-19, world leaders appearing via video link offered thanks and praise to Tedros and the WHO.

France’s president, addressing Tedros as “my friend,” urged major countries to come together to support the initiative, including China and the United States. “The fight against COVID-19 is a common human good and there should be no division in order to win this battle,” said Macron.

“It felt like a shot in the arm,” the second WHO official said. “It felt like there are people out there who are battling with us.”

(Reporting by Kate Kelland in London and Stephanie Nebehay in Geneva ; Additional reporting by the Beijing Newsroom, Steve Holland in Washington, D.C., Dawit Endeshaw and Giulia Paravicini in Addis Ababa, Katharine Houreld in Nairobi, Andreas Rinke in Berlin, Michel Rose in Paris and Kirsty Needham and Colin Packham in Sydney.; Editing by Cassell Bryan-Low)