TAILANDIA, Brazil (Reuters) – Mauro Lucio Costa wanted to do the right thing for the world’s largest rainforest.

For decades, the third-generation rancher in northern Brazil watched guiltily as his industry, feeding soaring global appetite for beef, razed ever more jungle. So, gradually he experimented with grasses and grazing techniques that today make his ranch one of the most efficient in Brazil. Costa became a model for those who believe beef can be raised profitably and sustainably – even in the Amazon.

As a so-called “finishing farm,” Costa’s ranch is the last stop cattle make in a chain that begins with breeders and often includes stays on a progression of other properties before animals are grown and ready for slaughter.

Eager to do more – and push others in the industry toward sustainability, too – Costa in 2017 decided to buy cattle only from breeders who could prove they weren’t ranching illegally cleared land. He asked a consultant to check suppliers’ farms for deforestation using satellite maps and a government list of embargoed properties.

After only a year, though, his effort failed.

Nearly half his cattle, Costa realized, came from suppliers who either had environmental violations or whose land titles and other paperwork were so questionable that he couldn’t be sure. To see his plan through, he said, he would have been unable to keep his herd populated and produce enough beef to make a profit.

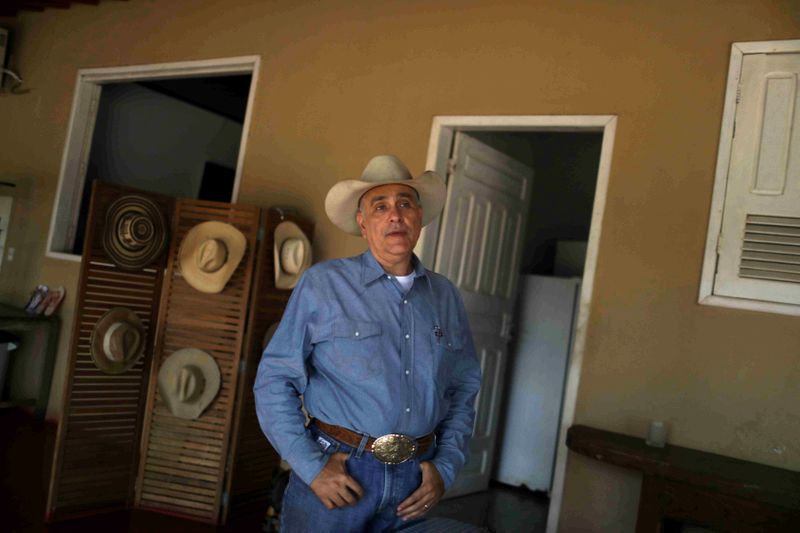

“I can’t sabotage my business for something no one else does,” Costa told Reuters, surrounded by pastures framed by towering rainforest. A wide-brimmed Resistol hat, a souvenir from trips to Texas, shielded his face from the tropical sun. His embossed belt buckle, also Texan, shone with his name and that of his ranch – Marupiara, an indigenous term that loosely means “place of happy hunting.”

The admission, from a rancher so “green” he addressed attendees of a United Nations climate gathering last year, illustrates the hurdles to responsible development in the Amazon jungle.

Costa’s effort was entangled by snags that have long hindered order in the vast, unruly region – from lax land registries to weak law enforcement to the opaque workings of Brazil’s beef business, in which cattle, with little or no tracking by government or industry, are reared and fattened on a succession of ranches.

It can be impossible for ranchers like Costa to know for certain where their animals hail from.

In many other major producers, like the United States, cattle move around less, living longer on single ranches and subsisting more on grains and prepared feeds. But Brazil’s cattle remain mostly grass-fed, using more pasture and leading ranches to specialize in particular stages of the animals’ growth.

While Brazilian law in theory makes it a crime to raise beef on illegally cleared woodland, few mechanisms exist to help buyers identify cattle’s origins. Livestock, like money, are often laundered, passing from pastures that violate environmental laws, into the legal supply chain, and on to supermarkets and dinner tables worldwide.

“There is a huge hole in the system,” said Paulo Barreto, one of Brazil’s leading researchers on land use in the Amazon. “No meat processor can say their cattle are deforestation-free.”

The Amazon, a jungle larger than Western Europe, is a crucial natural bulwark against climate change. It’s a major source of the world’s oxygen and fresh water, its vegetation a giant filter for greenhouse gases.

Although more than 80% of the original Amazon still stands, deforestation has accelerated in recent years as loggers, soy farmers and cattle ranchers, spurred by ravenous global demand, hack and burn deeper into the rainforest.

In addition to market forces fueling the devastation, President Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right populist, has reversed policies that prevented deforestation, slashing budgets of agencies that for decades fought unauthorized clearing.

Emboldened by the changes, Brazilians last year felled and burned rainforest equivalent in size to Lebanon, the largest clearing in more than a decade. This year, data suggest deforestation and fires in the Amazon continue apace.

International outrage is mounting.

VF Corp, the U.S. company that owns apparel brands including Vans, Timberland, and The North Face, said last year it would stop buying Brazilian leather. In May, British supermarkets threatened to boycott Brazilian products. In June, a group of major European investors said it was considering divesting its Brazilian holdings, including government bonds, if Bolsonaro doesn’t change course.

He has paid little heed.

Ricardo Salles, Bolsonaro’s environment minister, in April suggested that Brazil take advantage of the world’s distraction with coronavirus to accelerate deregulation of forestry laws. “We need to make an effort,” he said in a video of a cabinet meeting, “to push everything through, change it all, simplify norms.”

Last year, after a climate conference in Madrid, he tweeted a photo of a large, rare steak, joking that he was offsetting the meeting’s carbon emissions with “a veggie lunch.” When challenged by lawmakers, environmental activists, and Brazilian media about his comments at the cabinet meeting, Salles in a statement said he had always supported deregulation “with good sense” and “within the law.”

The ministry declined a Reuters request for further comment.

Once confined largely to the rolling pastures of Brazil’s temperate south, ranchers have used genetic advances to breed cattle that better weather equatorial heat.

In recent decades, ranchers pushed into the tropics, breeding the world’s largest beef herd, now with some 215 million animals. They also became the top exporters of beef, controlling about 20% of the global export market and selling almost 2 million tons of the meat annually to countries as far afield as China, Russia and Egypt.

A handful of Brazilian multinationals, including JBS SA, Minerva SA, and Marfrig Global Foods SA, ship most of those exports. But those meatpackers, from whom major retailers buy their beef, get the meat from a large and disparate array of suppliers, from small family farms to more sophisticated ranchers like Costa.

The Brazilian industry is recognized globally for strict sanitary policies and high-quality meat, but it has struggled to comply with its own nation’s forestry laws.

In 2009, Brazilian prosecutors threatened to identify and prosecute companies buying beef from illegal pastures. The big meatpackers, in response, started using satellite imagery and data to better track suppliers.

Deforestation slowed.

But the data only showed the land farmed by the immediate seller – not pastures where cattle grazed previously. Because there is no unified system to trace cattle transfers between ranches, going further has proven impossible.

JBS, Minerva and Marfrig, publicly traded companies with operations in dozens of countries, all told Reuters they recognize the problem with so-called “indirect suppliers” and that the industry and regulators must work together to solve it.

Just before Bolsonaro was elected in 2018, Brazil’s government drafted a voluntary agreement with major meatpackers and retailers to develop a tighter monitoring mechanism. The plan, previously unreported and recently reviewed by Reuters, would have used an existing system of livestock transport permits to track cattle movement.

“The Environment Ministry commits to developing a computerized system to verify the origin of cattle and the preservation of native vegetation,” the draft said.

But the Environment Ministry shelved the project after Bolsonaro won, according to three people familiar with the decision. “It could have really made a difference,” said Juliana Simoes, one of the people and a former ministry official who led the effort.

The ministry declined to answer questions from Reuters about the aborted agreement, saying only that it “supports the concept of traceability in agriculture.”

“LAND WITHOUT MEN”

For most of its history, the Amazon was considered a “green hell,” dense and inhospitable for almost anyone besides the indigenous peoples already living there. Save for isolated settlements along the region’s many rivers, colonists and Brazil’s early governments pursued little development.

In the 1970s, Brazil’s military dictatorship decided to build roads and promote migration, through cheap loans for land, to the Amazon. “Land without men,” the government slogan went, “for men without land.”

Costa, now 55 years old, first came when his father, a rancher like Costa’s grandfather, took a government loan for a parcel in the Amazonian state of Para. At first, the family continued living in southern Brazil, traveling occasionally to Para, where a young Costa watched his father clear jungle with hired hands and chainsaws.

At 17, Costa moved to Para for good, working for a while on his father’s ranch and later taking jobs at other ranches and a nearby slaughterhouse. Paragominas, the sawmill town nearby, was so violent it came to be known as “Paragobala” – “Paragobullet.” The farm had no electricity, the roads and surrounding woodland dangerous.

“I cried nearly every day,” he recalls.

Soon enough, he met a fellow rancher’s daughter. They fell in love, married and started a family.

Millions more Brazilians migrated to the Amazon. Wildcatters and squatters seized land without titles, forging deeds and other permits that still make the region a bramble of land conflicts and legal uncertainty. By the late 1980s, Amazon deforestation had become a signature issue of the modern-day environmentalist movement.

All around, Costa saw waste.

After loggers fell valuable timber, ranchers follow, plant grass and put cattle to pasture. Without the native flora, the once-rich soil dries quickly and loses nutrients. So ranchers move on.

“People just cut down more trees,” Costa said, driving past abandoned pastures near Paragominas. Deeper into the forest, he pulled near a large truck, with no license plate, stacked high with freshly cut hardwood. “All illegal,” he said.

At present, about 70% of the deforested land in the Amazon is used for cattle, according to estimates by Daniel Nepstad, a veteran ecologist of the region. The nine states that form the Brazilian Amazon account for 40% of the country’s herd. Para, a state larger than Texas and California combined, by itself accounts for about 10% of Brazil’s cattle.

Costa’s zeal for conservation came not from a love of nature, but of numbers. He keeps a large Casio calculator in his ranch office and punctuates his conversation with clicks on its keys.

In 1997, he struck out on his own, determined to find methods to avoid the wastefulness of slash-and-burn ranching. For about $190,000, he and a partner bought the land he currently ranches, near the Para town of Tailandia. A previous owner had cleared about 7% of the total plot of about 4,300 hectares, but it lay idle.

Costa planted new grasses. He fertilized the pastures and rotated cattle on a grazing schedule to optimize feeding times and grass growth. “Even a few hours can make a difference,” he said.

He currently farms about 500 hectares, roughly the size of 700 professional soccer fields. Because of a perverse irony of Amazon real estate, Costa actually leaves money on the table by not clearing the remaining 80% of his land.

Despite the ecological wealth that woodland represents, cleared land sells for multiples what virgin rainforest does because farmers find it more useful. The dynamic discourages conservation, incentivizing destruction even if fields aren’t ranched.

“Even my father-in-law thought I should cut more trees,” Costa said. “Forest doesn’t create value.”

When leftist Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva became president in 2003, he sought to tackle deforestation. His government created nature reserves, better tracked logging and forest fires, and eventually blocked financing for farmers and ranchers caught working illegally cleared land. By the time Lula finished his second term, the annual rate of deforestation had plummeted almost 75%.

Costa, meanwhile, further improved his grazing practices. He took soil samples, analyzed land chemistry and increased the number of cattle that could graze each hectare he ranches. He also received threats, he said, from people scorning his decision to leave so much forest intact.

“I suffered a lot of bullying,” he said. “If you don’t use it, someone else will,” anonymous callers warned, a threat not easily dismissed in a region rife with squatters and murderous land disputes.

Still, his methods paid off.

Costa now ranches nearly four times as many head per hectare than the average in Brazil, according to government statistics. By that metric, if other ranchers in the Amazon became as efficient, an area the size of France could be reforested on land today grazed by cattle.

Seeking the secrets of his success, such as the seven different grasses he now grows, fellow ranchers visit Costa often, eager for a peek in the neat black ledger he carries. “He’s the best there is,” said Jordan Timo, a fellow rancher and the consultant Costa asked to help him track suppliers.

“PREACHING IN THE DESERT”

Brazil’s gains against deforestation early this century were shortlived.

A global commodities boom a decade ago fueled greater demand for beef and soy. Former President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s successor, sought to leverage the commodities bonanza to revive big infrastructure projects in the region. She relaxed regulations on nature reserves and pursued major hydroelectric projects on Amazon tributaries.

By 2015, the boom fizzled, draining government revenues. Rousseff and her successor, Michel Temer, cut financing and stripped powers from Ibama, Brazil’s environmental agency. State and municipal authorities, squeezed by budget shortfalls of their own, struggled to fund law enforcement vital for monitoring destruction locally.

Deforestation rebounded.

After early success tracking supply, the 2009 agreement with meatpackers to better monitor ranches yielded less progress than hoped for. JBS, Minerva and Marfrig say they continue to monitor the land of their immediate suppliers. But they remain unable to track where those vendors get the animals. Smaller meatpackers, meanwhile, never signed the agreement.

Prosecutors in charge of environmental enforcement say any further crackdown, tracing beef throughout the industry, would in essence halt Brazil’s cattle business. “You would destroy the meatpacking industry,” said Ricardo Negrini, a federal prosecutor in Belem, Para’s capital. “It has to be done gradually.”

Holly Gibbs, a geographer at the University of Wisconsin who has investigated land use by Brazil’s beef industry, said only about 3% of cattle in Para and nearby states spend life on just one farm.

Ranchers have all manner of tricks to get around controls, like splitting their tracts into separate titles, enabling them to graze cattle on illegally cleared pastures but then sell those animals from seemingly legitimate land.

The industry is so opaque that even ranchers sanctioned for deforestation sell their cattle easily. Moises Berta, who ranches near the frontier town of Novo Progresso, was fined by Ibama in 2016 for illegally cleared land. He admits he cleared the tract, but said he had no other choice to make a living.

The fine means his farm shows up on lists used by major meatpackers to block vendors. Berta said he has no trouble, however, getting his beef to market via middlemen or smaller slaughterhouses. On the downside, he said, these buyers pay about 20% less than the majors. “It’s a difficult situation,” the 61-year-old told Reuters.

There are over 37,000 parcels in Amazon states that have been sanctioned by Ibama for environmental crimes. Fines are meant to blacklist areas for commercial use until owners replant cleared forest. In practice they do little more than force ranchers like Berta underground.

For the methodical Costa, the preponderance of illegal ranching thwarted his effort to ensure a clean supply.

About a third of his cattle, he calculated, came from land that has been sanctioned. Another 15% came from ranches with deeds and other paperwork that don’t jibe with public registries, making it impossible for Costa to check their land against embargo lists.

The math in his black ledger spoke clearly.

To recoup his investments in priming his pastures, Costa needs to boost his herd count from about 1,700 to 2,500 cattle each year just as the rainy season begins, usually in mid-December. The timing matters because that’s when cattle can take advantage of the sudden acceleration in grass growth brought by the rain.

If the herd is too small, some of the grass goes to waste. If he misses the window, Costa must spend yet more to buy feed. If Costa blocked cattle suppliers he knew or suspected had illegally cleared land, he realized, his herd wouldn’t reach the critical mass necessary for “as aguas,” as the rains are called.

Instead of his usual profit of roughly $85 per animal, Costa would have suffered a loss of about $50 per head. “It just wasn’t going to work,” he explained.

He abandoned the effort.

As a result, Costa himself plays an indirect role in perpetuating at least some of the illegality. He feels tethered, he said, with few options to change a system that keeps him from ranching the way he believes he should. “I feel like I’m preaching in the desert.”

(Editing by Paulo Prada)