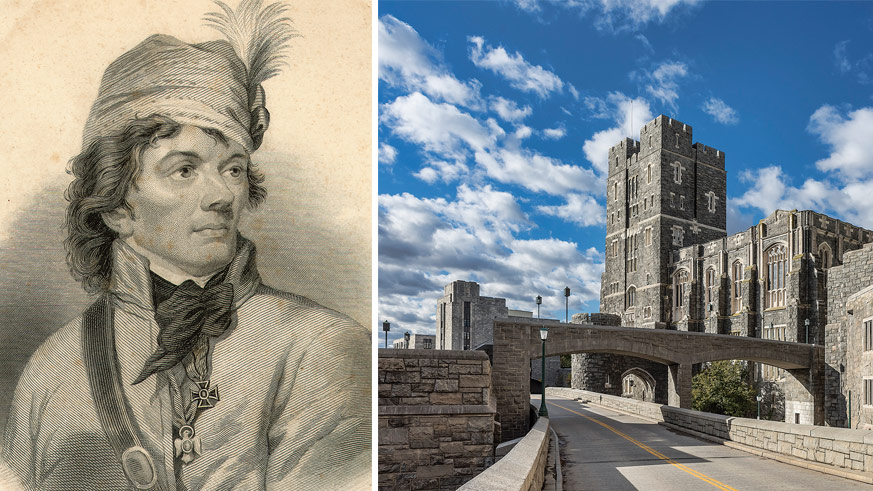

He was the Polish and American hero who built West Point. The immigrant engineer who launched the world’s first firework display on July 4th. And the humanitarian who called for the emancipation of both slaves in the United States and serfs in Europe.

This year UNESCO celebrated the 200th anniversary of the passing of Tadeusz Kościuszko. And for good reason—he’s the soldier with more monuments across America than anyone but George Washington.

Back in 1777, the Battle of Saratoga was the tipping point in the American Revolutionary War against the British. As the Continental Army retreated across the Hudson River, Kościuszko had scouted out a defensive redoubt for a last-ditch battle.

Bemis Heights was the site he fortified. On October 7, five thousand Redcoats stumbled through forests straight into American lines. It was a small battle, perhaps, but the pivot in a global conflict.

News of the subsequent surrender of British General Burgoyne spread like wildfire. French King Louis XVI weighed in with loans, arms, soldiers and supplies for the Americans, giving them the longevity to run a war of attrition that would force the British back across the Atlantic.

“Kościuszko always stood up for the little guy,” says Alex Storozynski, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Kościuszko. In his book The Peasant Prince: and the Age of Revolution, he tells the story of an African slave who had been captured by the British. “As Kościuszko had a British officer in custody, he suggested a (one-for-one) exchange for the slave.”

Kościuszko returned to Europe after the Revolutionary War.

In time, an even more pressing threat arose on the horizon. Kościuszko’s call for liberty terrified Poland’s neighbors. After Poland proclaimed the first Constitution in Europe and the second in the world in 1791, Russia invaded with overwhelming force.

Kościuszko’s military know-how, acquired on the battlefields of New York State, came to the fore. He lost not a single battle, winning the Virtuti Militari—the equivalent of the American Medal of Honor, it remains Poland’s highest military decoration.

But playing politics was never Kościuszko’s game. He stood aside as cynical deals with Poland’s neighbors—Russia, Prussia, and Austria—steadily reduced the country’s size. Russian and Austrian authorities hunted him as he passed through Zamość, Kraków and Wrocław (today three of Poland’s most beautiful cities, and each a UNESCO heritage site).

He returned to Poland in 1794 to wage war against his nation’s occupiers. It became known as the Kościuszko Uprising.

Such was his personality that volunteers flocked to join him. In the forests near Kraków, he personally led a peasant infantry charge that struck the first blow against Russian might.

After defending the Polish capital of Warsaw, he battled an overwhelming Russian force near the village of Maciejowice. Three horses were shot out from under him before Cossack irregulars stabbed him from behind. The Russians were victorious, and after the battle they searched the corpses lying in the mud for the wounded Polish commander. But Kościuszko had survived, and was carried from the battlefield in a peasant’s robe, before later being captured.

Kościuszko was a man of his word. When he was released by Tsar Paul, he promised never again to fight against Russia. Years later he was courted by Napoleon, but never trusted the Great Conqueror. Kościuszko preferred to remain a living symbol of the Revolutionaries’ slogan—Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—than to be an oath-breaker.

Even in death, Kościuszko championed equal rights. In his will, he decreed that all of his estate go to his “friend Thomas Jefferson to employ the whole thereof in purchasing negroes from among his own as any others and [give] them liberty.” He asked for his funds to pay for the education of these newly-freed people, and by doing so sent a clear message not only to Jefferson, but to the entire world. In 1817, the year Kosciuszko died, New York passed a law abolishing slavery.

With this defeat the Polish nation was erased from the map for 123 years. But today his name graces Australia’s highest mountain, an island in Alaska, and a thousand streets, squares and parks around the world. Thanks to his heroism in the United States and Poland, Kościuszko has not been forgotten.

The Kosciuszko Bridge Cocktail

he Kosciuszko Bridge is a cocktail created for ‘The Vodka Contract,’ a special event from the Spring Spirits series at Brooklyn’s Museum of Food & Drink (MOFAD) under the auspices of the Polish Cultural Institute New York. This aromatic concoction is a melding of the Polish herbal Bison Grass vodka, Żubrówka, with New York’s own Dorothy Parker Gin, and a splash of Doc’s Draft Cider. Created by Joel Lee Kulp of Grand Ferry tavern in Brooklyn, it’s the perfect drink to ring in the New Year.

The Kosciuszko Bridge

• 1oz Żubrówka (Bison Grass Vodka)

• 1oz NY Distilling Dorothy Parker Gin

• 1oz Doc’s Draft Cider

Combine all ingredients, stir, and serve over ice in a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with dry bison grass or rhubarb peel.

This article is sponsored by Polish Culture Institute New York