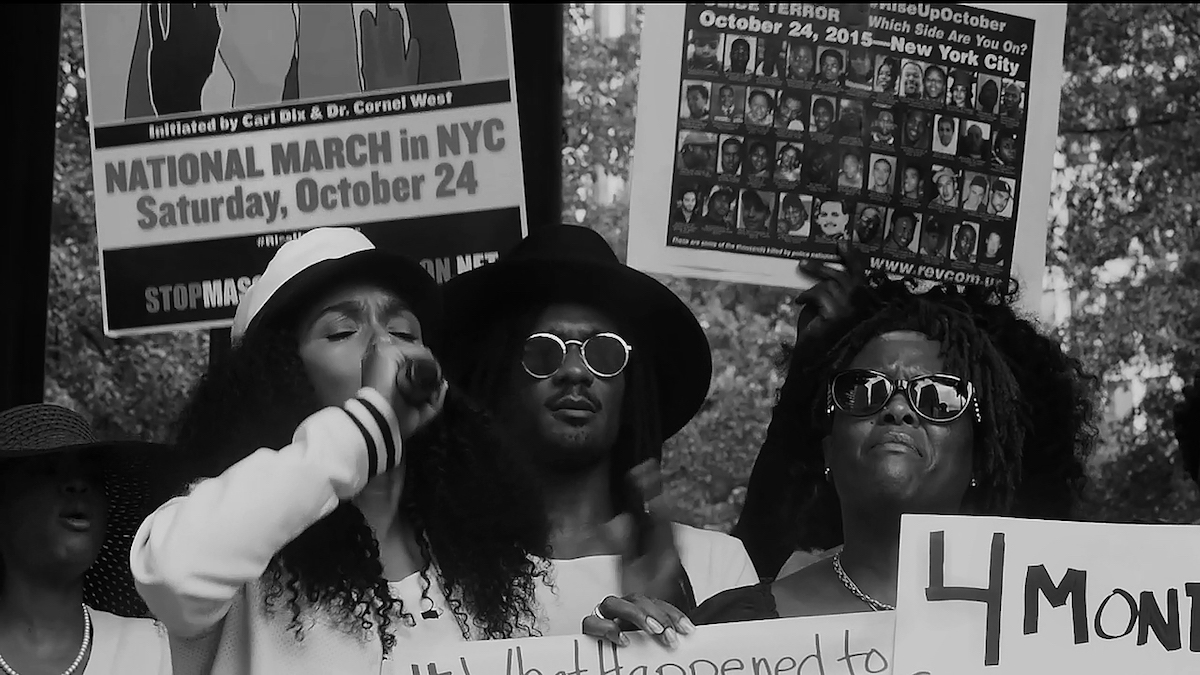

We live in a time of not just change but Perpetual Revolution, and there’s nothing more powerful than the right image to drive — or stifle — social change. That’s the premise of the International Center of Photography’s latest exhibit, the first in its Year of Change series looking at visual media’s impact on the world, using both iconic images like NASA’s “Earthrise” photo taken by Apollo astronauts and newly impactful images from the Black Lives Matter movement, along with videos, magazines and even real-time social media feeds. RELATED: Georgia O’Keeffe was a style icon in her day If the range of media sounds impressive, it’s because the exhibit doesn’t just cover one topic. There are six areas of focus: Black Lives (Have Always) Mattered, The Fluidity of Gender, Climate Changes, Propaganda and the Islamic State, The Flood: Refugees and Representation, and a late addition to the show, The Right-Wing Fringe and the 2016 Election. “The curators felt that those case studies would serve as interlocking, yet different ways of seeing how the networked image was affecting social change,” explains ICP head of exhibitions and collections Erin Barnett. Going beyond still photos was necessary to remain relevant in a world of memes and Facebook Live. “We had to rethink how people were using images, taking images and sharing images.” The idea of images as indisputable evidence is no longer necessarily true either — and it’s not just because of Photoshop. We talked to Barnett about why what you’re seeing may not be the whole story. When images hurt

Images of desperate migrants coming across water have been part of the dialogue about immigration since World War II, when hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors who couldn’t return home sought a new life elsewhere. Often, including in the U.S., they faced the same rejection as the refugees now fleeing conflict in the Middle East and Africa. “You look at some of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs of the recent refugee crisis and you see the same visualization of massive amounts of people,” says Barnett. “We thought it was important to show it had happened in the past and is continuing to happen now.” The problem with these images is they gave rise to phrases like “the flood of migrants” or “the tide of refugees” — it’s not hard to see how the problematic association with natural disasters could inspire anti-immigrant sentiment.

When the image changes based on who creates it

The perspective of refugees is not one we had much access to previously. Social media has changed that, empowering them to show their strength and resilience instead of letting politicians and activists spin their own narrative. A piece by Belgian documentary photographerTomas van Houtryvewas created by compiling geotagged images from Instagram along Western European migration routes.

“So basically,” Barnett says, “it looks like happy people; they don’t look like tired, huddled masses. Yes, they’re on a difficult journey, but most of them seem happy to be in the place that they are because they’re farther away from what was going on in their home country.”

When an image is ignored

While the other sections of the exhibit had extensive historical records to draw from, the genderfluid community and cultural institutions are still building up a history that’s largely been ignored or even erased. “It starts with a history collage, and part of it is about reclaiming images that weren’t saved in museums or by collectors and trying to recreate this history,” says Barnett.

But it’s also about seeing what’s always been there but ignored in well-documented events like the Harlem Renaissance but through the lens of photographerCarl Van Vechten. “The exhibition is trying to situate gender non-conforming and non-binary people and other historically marginalized groups — like African Americans or refugees — in a larger context.”

When an image doesn’t show everything

Marginalized communities face a problem when they want to present themselves to the rest of the world. Do they change their appearance or omit certain aspects of their experience to be more readily accepted? Present themselves truthfully, and they might end up on “Maury” being called freaks (the exhibit includes clips). Then again, not all trans women are the glamorous figure struck by Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair.

In the end, both remain mainstream representations. The ICP curatorial team sought out images of voguing, ballroom culture and clubs, which were a place for trans people to find community and safety, as well as magazines by and for trans people.

When an image loses its context

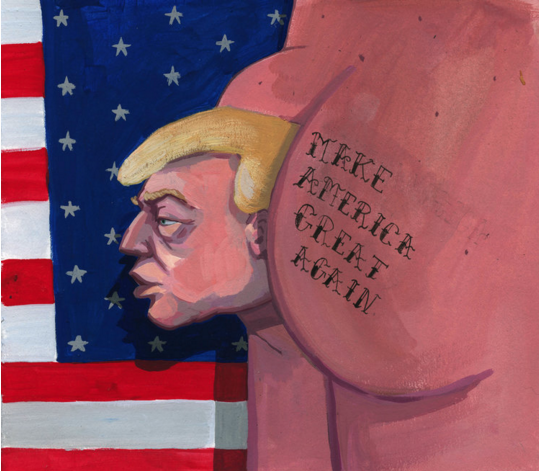

“It was clear that Trump’s team managed social media in a different way, and so we wanted to address that,” says Barnett of the last-minute addition inspired by Donald Trump’s campaign. Among the most problematic aspects is how Pepe the Frog, who went from being a comic book character to a symbol for the alt-right, has appeared not just onDonald Trump Jr.’s Instagram accountbut other officials close to the administration. Burger chainWendy’s also tweetedits own take on the meme — presumably without knowing its problematic history. “Part of it is about not knowing where these images originated and how viewers maybe read them entirely differently than the way that they were intended by their original audience,” explains Barnett. “It’s unclear when people are using images online if they understand what they mean.” Sometimes, an image may not replace 1,000 words — it might need that many to explain it. When images differ based on audience

The promise of virgins and killing infidels may make for attention-grabbing headlines when discussing what motivates people to join ISIS. But the videos you’ll see at ICP are the ones ISIS shows in the countries where it operates — their real recruiting tools, which promote compassion and safety. “They have these high production value videos that present their ideal state as this utopian vision where there are new markets and new hospitals, feeding children and taking care of the elderly, which looks very different from what we generally see in the Western media,” says Barnett. “We’re arguing for some sort of visual literacy and paying attention to what you’re seeing and understand what the historical context of those images is, but also the power of those images and how they can create a different reality.”