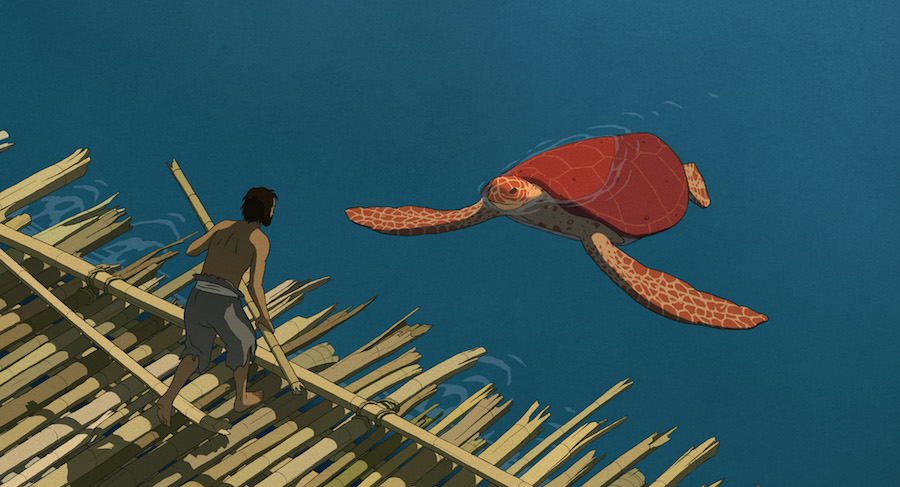

‘The Red Turtle’ There’s something off about Studio Ghibli’s latest animated opus. It’s nothing to do with quality; the design-work remains top-notch, its rough, serene hand-drawn digs an antidote to the shiny CGI clutter that’s taken over America’s multiplex toons. It’s the look, the feel, even the content that’s ever so slightly different. There’s a reason for that: It’s the first feature from the Japanese animation outfit not made in-house. And how: A co-production with Euro agency Wild Bunch, it boasts a director-cowriter, one Michael Dudok de Wit, who hails all the way from the Netherlands, while the other writer is Frenchwoman Pascalle Ferran (who also helmed 2006’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” — hardly someone you’d call for an ostensibly all-ages product). Still, the results aren’t that different. The humans may have beady eyes, there’s not a trace of spoken dialogue beyond the occasional “Hey!” and the tale is more allegorical than usual — closer to a fable than a shape-shifting wonder like “Spirited Away.” Yet “The Red Turtle” is another Ghibli where nature reigns, where the world is capable of surprising magic, where the line separating reality and fantasy is porous and messy. It’s like a Brundlefly fusion of two worlds that aren’t so different after all. It opens with one of those minimalist design wonders only Ghibli bothers crafting these days: a few sleek black lines over a blue background — all one needs to depict a torrential storm at sea. Our unnamed hero is adrift inside it, for reasons we will never learn, soon washing ashore on a tiny, remote island. The early stretches recall “Cast Away,” the first half of “The Black Stallion,” even the start of last year’s “Swiss Army Man.” Instead of a volleyball, a racing horse or a farting corpse, this one scores an improbably huge and vaguely sentient red turtle. But their relationship doesn’t start swimmingly: Every time he builds a bamboo raft to escape, the creature butts it to pieces with its shell. Eventually he’s had enough: One day when the turtle waddles on to the beach, he flips him over, dooming it to bake in the sun. His conscience soon gets the better of him, but it’s too heavy to flip back. RELATED: 13 happy movies to keep you sane in the Trump Age What follows can be read in a few ways: One day our protagonist discovers that the turtle has left its shell and turned into a fetching woman, complete with a flowing reed mane. He gives up, resigning himself to a pleasant life of island-bound domesticity, soon joined by a son. Is this a fever dream — a Ballardian fantasy in which reality becomes the projection of a frazzled mind? Is this magical realism, in which nature conspires to imprison him or save him, perhaps gifting him with a superior life away from the things of man? Or, better yet, should we resist interpretation entirely, and accept that the film dwells in the liminal space between these two extremes? We’d argue for the latter, and the filmmakers would seem to agree. Unhurried, placid and, yes, a needed respite from the outside world, “The Red Turtle” keeps one foot in the real and the other in the super-real. Instead of psychdelics, De Wit stays plain, depicting a natural world that’s quietly intruded upon by the abnormal. While the critters (crabs, bats, little fishies) are slightly anthropomorphized, that doesn’t keep them from harm’s way, as it would in a Disney outing. A man’s got to eat, though de Wit makes sure to throw in a shot of a fish going about its business before it meets the blunt end of a sharpened stick — making sure we think of it as a being, not mere human food. (A braying seal also meets an unhappy end, though not by his hands.) Otherworldly though it might be, “The Red Turtle” exists in a tough and dispassionate world, red in tooth and claw. We even get an early scene where the unnamed man, trapped in a watery alcove, must wriggle through a narrow cave portal to safety — the most nail-biting of its kind since “The Descent.” You can read this gorgeous and soothing semi-fantasy as an honest and gutting look at one man’s bottomless guilt — or you could bend your logical mind and accept it as that and so much more.

Director: Michael Dudok de Wit

Genre: Animation

Rating: PG

4 (out of 5) Globes

‘The Red Turtle’ is an unusual but reliably soothing Studio Ghibli film

Sony Pictures Classics

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge