Pumpkins are among the royalty of the fruit world. Starbucks’ Pumpkin Spice Latte is the 21st-century equivalent of the Fall Equinox, jack o’ lanterns are an entire art form, and we haven’t even started talking about pies. But decorative gourds are not the only squashes grown for show — giant pumpkins are serious business among the nation’s farmers, and the biggest of them end up in the New York Botanical Garden’s Spooky Pumpkin Garden, open through Oct. 31.

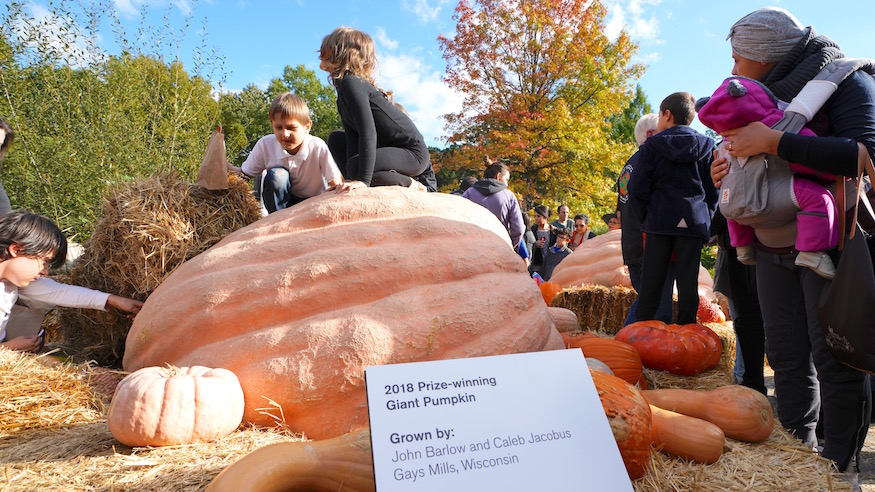

It’s the most prestigious place for a giant pumpkin to end up, according to Caleb Jacobus. He would know — the Wisconsin farmer is a member of the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth and the co-grower along with John Barlow of the fourth largest giant pumpkin in the entire world this season, weighing in at 2,283 lbs.

“For the kids to see it, that’s what it’s all about, really,” he says, looking on as kids ages 2 to 12 turned his produce into a jungle gym last Saturday. “There’s nothing better than to have literally thousands of kids come by and sit on your pumpkin. That’s probably the happiest pumpkin there ever was.”

So what does it take to grow a giant pumpkin? Ingenuity, a lot of hard work and one special superfood.

How to grow a giant pumpkin

The single most astonishing fact about giant pumpkins is how fast they grow. From seed to prize-winning gourd takes less than 90 days.

Growing a giant pumpkin starts in early April. Seeds have to be pre-soaked in water for several hours then transferred into a bucket of enriched soil, and are kept in a room at 85 degrees in early April.

Once the seeds germinate, the buckets go in front of a sunny window for a couple weeks to develop roots. Meanwhile outside, Jacobus has already built the individual greenhouses for each giant pumpkin he plans to grow — four this season — which are busy warming up the soil. “Giant pumpkins are so labor intensive that if you tried to grow any more, you wouldn’t be able to put the time into it,” he says.

Wisconsin falls in the Great Pumpkin Belt, which stretches from Washington state to Nova Scotia and tends to produce the largest pumpkins because temperates are neither too hot nor too cold. But you still have to find ways to heat up and cool down giant pumpkins, which are particularly delicate creatures: “If it’s under 50 degrees at night, then the plant will shut down; if it’s over 70, it can’t store carbohydrates,” explains Jacobus.

Seeds go into the ground at the start of May, planted in soil tilled with maple leaves, hydrolized fish, chicken pellets, worm-friendly synthetic fertilizer and the superfood seaweed — it has 72 trace minerals. All that good food means once the pumpkin gets going, it will almost outgrow its 12-by-12-foot triangular (less wind resistance) greenhouse in about a month. “At 40 days old, this pumpkin was over 1,000 lbs.,” he says. “During peak growth, it’ll grow 50 lbs. a day.” You can almost hear it growing!

After that, you try to block as much wind as possible and start the hard work. Every day, the vines of each pumpkin grow up to 2 feet, which must be constantly covered by soil and trained to grow in a certain way to keep the pumpkin growing. Just watering each pumpkin takes up to an hour every other day.

Oh, and Jacobus fits all this in between running the rest of his farm, five kids, coaching two sports and being an amateur bodybuilder. (Giant pumpkins are also not the only produce he grows for competition: giant green squash, which he and Barlow grew two world record-breaking specimens of this season, plus bushel gourds, long gourds, watermelons and tomatoes in pursuit of the Master Gardener title.)

But doing it the old fashioned way is what’s gotten him these results for 13 years. “I know people that are millionaires that grow their own pumpkins and spend thousands of dollars per plant,” he says. “This plant would have less than $500 for the whole year to grow it. It’s mainly the elbow grease.”

After Halloween night, Jacobus and Barlow’s giant pumpkin and the three others in the garden will continue to delight kids in a new way: as fertilizer. They’re combined with leaves and pruned branches to become nutrient-rich compost that will help grow the next season’s flowers and trees.