One of the 20th century’s greatest spy stories has just been declassified, and the entire saga from capture to trial is now on display at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Lower Manhattan.

Few Nazi soldiers are as notorious as Adolf Eichmann, who oversaw the mass incarceration of Jews into ghettos and their eventual deportation to concentration camps. Through 130 artifacts from the archives of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad, “Operation Finale” reveals how he was captured after fleeing to South America, smuggled out and convicted in the first mass-televised trial.

“The exhibit is not about Eichmann,” says Yitzchak Mais, a consulting curator on “Operation Finale,” which opens July 16. He describes the SS lieutenant colonel as a technician of the highest order, who tried to win sympathy at trial by claiming that he didn’t directly kill any Jews. “It’s more the cloak-and-dagger story of how he was caught by Mossad, and the trial that followed.”

And what an operation it was. After the end of World War II in 1945, Eichmann fled to Argentina, where the Vatican and the Red Cross helped (whether intentionally or not) many Nazi officers resettle with new identities.

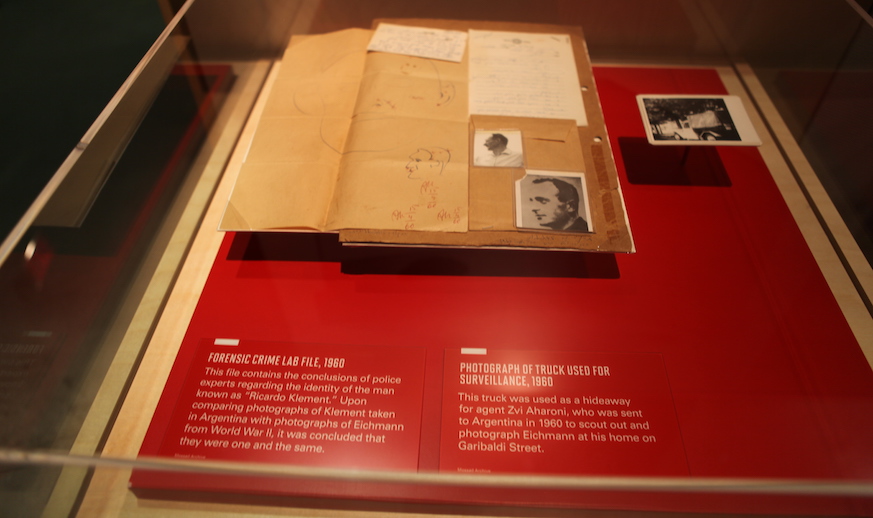

“Operation Finale” picks up when the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, who was admitted to the country as a refugee, begins dating the son of Eichmann, who went by the name Ricardo Klement. Once the family became suspicious of Eichmann’s true identity, Mossad began planning how to capture him.

“Mission Impossible,” this was not. The extensive pre-digital era espionage tools on display include such cutting-edge techniques as the dip pens used to forge the documents that allowed Eichmann to be taken out of the country as a crewmember of the Israeli airline El Al, plus fake license plates (with a printing kit in a suitcase!) and even the South American travel guide the Mossad agents carried for their cover as tourists.

Eichmann was captured in May 1960, almost 15 years after the end of the war. By then, memories of the Holocaust had begun to fade, but his trial the following year would prove to change the course of history. “The intensity of these survivor testimonies helped shine a light on these atrocities for a public, that at the time truly didn’t know about what had happened during the Holocaust,” explains Michael Glickman, the new president of the museum.

Millions around the world watched the trial on television every week, and the museum puts visitors right inside the courtroom. The exhibit ends with a small theater that has the original glass booth where Eichmann sat in the courtroom at its center; footage from the trial is projected on the walls surrounding it.

The chilling figure of Eichmann is projected inside the booth, impassive as the 210 witnesses — 90 percent of them survivors, says Glickman — recounted atrocities like having children torn from their arms and being forced to choose between saving their wife or mother. Loyalty to his country, Eichmann says, was more important than their deaths.

“As we move to a time when there are fewer and fewer survivors,” says Glickman, “to be able to put visitors into that courtroom and hear their words first hand, it gets me every time.”

Three judges decided the trial, finding Eichmann guilty of crimes against humanity, and sentencing him to death. When he was hanged in 1962, Eichmann became the only Nazi ever executed by Israel in connection with the Holocaust.

If you go

Operation Finale

July 16-Dec. 22

Museum of Jewish Heritage, 36 Battery Place

$12, mjhnyc.org