(Reuters) – The anti-China trade mood has reached U.S. kitchens, where a battle is being waged over competing visions of where and how cabinets should be made.

On one side are America’s traditional cabinet companies, employing an estimated 100,000 people in factories across the country, often in small towns close to forests supplying the wood. On the other is a new breed of “ready-to-assemble” firms that grabbed a hefty slice of the business over the last five years by importing disassembled cabinets from China in flat boxes and selling them at unbeatable prices.

In March, the International Trade Commission ruled unanimously in favor of a coalition of 50 U.S. firms fighting to stop the influx. The ITC concluded the imports charged unfairly low prices and slapped on big anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties that will last five years.

“We did this for the American worker,” said Mark Trexler, chief operating officer of Cabinetworks Group, the nation’s second-largest cabinet maker and a member of the coalition.

While cast as a Chinese cabinet invasion, the ready-to-assemble rise was driven largely by domestic companies, including some of the biggest U.S. players who invented the niche and went to China to source products. Chinese companies have jumped into the business, to be sure, but ready-to-assemble was an American idea. The upshot for Americans from the trade case is likely to be higher cabinet prices.

And Trexler’s assertion notwithstanding, jobs are not coming back to U.S. shores because of tariffs. Even as the case was being fought, ready-to-assemble firms like CNC Cabinetry, a privately held company in South Plainfield, New Jersey, were getting out of China – by shifting work to other low-cost countries.

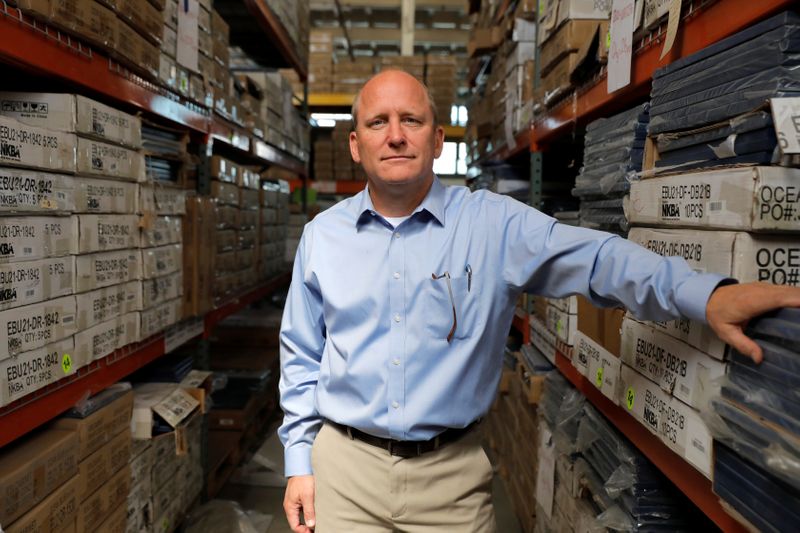

Robert Hunter, CNC’s chief operating officer, said no domestic companies will make the disassembled product for him to replace the Chinese supplies – at least not at a competitive price. So he shifted sourcing to Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia and is hunting for a low-cost option in Eastern Europe to have many options for sourcing at a time of spreading trade battles.

SPEED IS ESSENTIAL

CNC was founded in 1992 as a traditional cabinetmaker but shifted to ready-to-assemble after the 2007-2009 recession. At a sprawling facility just outside New York City, rather than making cabinets from scratch, most of the space is devoted to shelves of flat boxes. The key is to have a ready supply of a limited range of sizes and styles, Hunter said.

When a customer calls, Hunter can ship the boxes containing all the parts needed for a cabinet immediately or have his small staff of 50 craftsmen assemble it so the cabinets are ready to install when delivered. The New Jersey facility also makes countertops, which aren’t imported, to finish off a kitchen package.

“If you call me today in the morning, I’m shipping tomorrow night,” said Hunter.

CNC sells mostly to builders outfitting multiple kitchens and house flippers looking for low prices. Traditional cabinet companies can take weeks or longer to deliver cabinets.

Ready-to-assemble’s rapid growth sparked the trade case, say manufacturers, importers and trade attorneys for both sides interviewed by Reuters. The U.S. cabinet industry sells about $10 billion worth of goods a year, and while the two sides dispute how big ready-to-assemble has grown, the ITC noted Chinese imports of cabinets, vanities, and cabinet parts totaled about $4.4 billion in 2018.

Many domestic firms feared they were following the path of America’s furniture industry, which began selectively importing Chinese products in the 1990s and was eventually swamped by direct competition from Chinese producers entering the U.S. market. Parts of North Carolina are still dotted with empty furniture factories as a result.

Ready-to-assemble cabinets were depressing prices for everyone, according to domestic firms. They were also coming equipped with features for which U.S. producers had always charged extra, like self-closing drawers.

“History shows the Chinese aren’t satisfied until they have the whole industry,” said Stephen Wellborn, co-owner of Wellborn Cabinet Inc in Ashland, Alabama. He said the political climate was favorable, given President Donald Trump’s commitment to helping domestic manufacturing, but he said they would have brought the trade case anyway.

One irony is that the largest U.S. cabinetmaker, Fortune Brands Home & Security Inc’s <FBHS.N> Masterbrand Cabinet unit, helped develop the ready-to-assemble business in China before deciding it posed a risk to its much larger domestic operations. Masterbrand’s U.S. sales were $2.5 billion last year, and it has 10,000 U.S. employees in 20 factories fed mostly by U.S. suppliers.

Masterbrand said it stopped buying from China after the case was filed. But it did not bring those jobs home either. The company now obtains ready-to-assemble cabinets from Vietnam. Cabinets made in Vietnam are 30-40% pricier than China, according to industry sources.

Back at CNC, Hunter said he was also anticipating more trade issues. If shipments grow too much from another country, such as Vietnam, the United States could crack down with duties on those imports as well, he said.

“That’s why I want to find sources in five countries, minimum,” said Hunter, “because you don’t know what comes next.”

(Reporting by Timothy Aeppel in Fairfield, Conn.; Editing by Dan Burns and Matthew Lewis)