WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. corporate profits surged to a fresh record high in the second quarter, boosted by robust demand and higher prices, suggesting that an anticipated slowdown in economic growth this quarter because of soaring COVID-19 cases could be temporary.

The jump in profits reported by the Commerce Department on Thursday was despite businesses facing increased costs owing to shortages of raw materials and labor. The resurgence in infections driven by the Delta variant of the coronavirus is chipping away demand for services like air travel and cruises, leading economists to cut their third-quarter growth estimates.

“Based on the profits data, any slowdown in growth as a result of slower consumer spending is likely to prove temporary,” said Conrad DeQuadros, senior economic advisor at Brean Capital in New York.

Profits from current production increased by $234.5 billion, or at a 9.2% quarterly rate, to a record $2.8 trillion, after rising at a 5.1% pace in the first quarter. They were driven by a $169.8 billion surge in profits at domestic nonfinancial corporations. There were also gains in domestic financial corporations profits as well as rest-of-the-world profits.

Pre-tax profits as a share of GDP, a proxy for economy-wide profit margins, rose 0.7 percentage points to 12.3%, their highest since 2014.

National after-tax profits without inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments, conceptually most similar to S&P 500 profits, increased $303.6 billion, or at a 12.8% pace, up from the 9.4% pace notched in the January-March period.

Profits were up 69.3% from a year ago, partially exaggerated by low base comparisons in the second quarter of 2020 following mandatory shutdowns of nonessential businesses.

“Elevated margins suggest higher costs have not yet meaningfully eaten into firms’ profits, as firms appear to have more pricing power today than they typically would this early in an expansion,” said Jay Bryson, chief economist at Wells Fargo in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Gross domestic product increased at a 6.6% annualized rate, the government said on Thursday in its second estimate of GDP growth for the April-June period. That was revised up from the 6.5% pace of expansion reported in July.

Economists polled by Reuters had expected that second-quarter GDP growth would be raised to a 6.7% pace. The economy grew at a 6.3% rate in the first quarter, and has recouped the steep losses suffered during the two-month COVID-19 recession.

The level of GDP is now 0.8% higher than it was at its peak in the fourth quarter of 2019. The upward revisions to last quarter’s GDP growth reflected a slightly more robust pace of consumer spending and business investment than initially estimated. Demand was driven by one-time stimulus checks from the government to some middle- and low-income households.

The Federal Reserve has maintained its ultra-easy monetary policy stance, keeping interest rates at historically low levels and boosting stock market prices.

Stocks were trading lower. The dollar rose against a basket of currencies. U.S. Treasury prices were mostly lower.

SPEED BUMP

Consumer spending, which accounts for more than two-thirds of the U.S. economy, appears to be cooling. Credit card data suggests spending on services like airfares, cruises as well as hotels and motels has been slowing.

“This is a speed bump due to the interaction of Delta and supply-side constraints,” said Michelle Meyer, chief U.S. economist at Bank of America Securities in New York. “We still believe the foundation for the economy is solid and all signs point to strong underlying demand.”

Bank of America Securities has slashed its GDP growth estimate for the third quarter to a 4.5% pace from a 7.0% rate.

Growth is expected to pick up in the fourth quarter, in part driven by businesses replenishing inventories, which were drawn down in the first half of the year to meet the strong demand. Overall, economists expect growth of around 7% this year, which would be the strongest performance since 1984.

Though the boost from fiscal stimulus is waning, demand remains underpinned by a strengthening labor market.

A separate report from the Labor Department on Thursday showed initial claims for state unemployment benefits rose 4,000 to a seasonally adjusted 353,000 for the week ended Aug. 21.

Adjusting the data for seasonal fluctuations is tricky around this time of the year, a task that has been complicated by the pandemic. That could account for the increase in applications last week. Unadjusted claims dropped 11,699 to 297,765 last week.

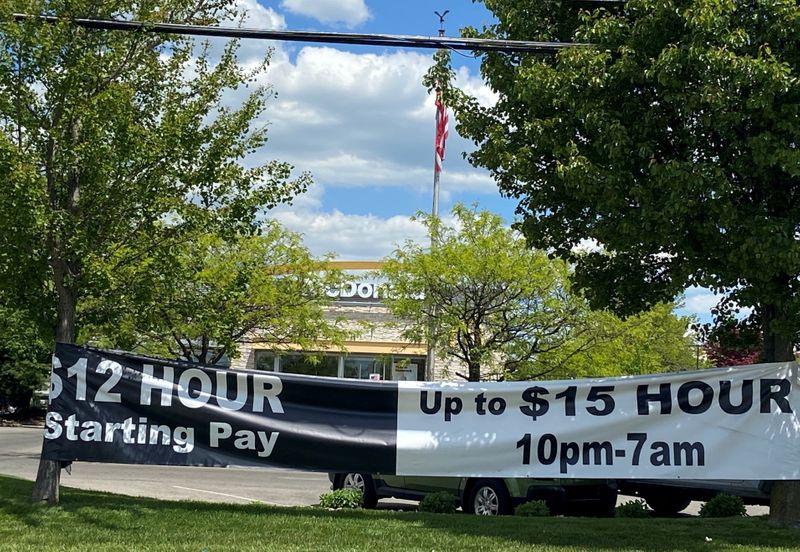

Companies are clinging to their workers amid worker shortages blamed on a lack of childcare facilities and fears of contracting the virus. There were a record 10.1 million job openings as of the end of June.

At least 25 states led by Republican governors have pulled out of federal government-funded unemployment programs, including a $300 weekly payment, which businesses claimed were encouraging unemployed Americans to stay at home.

There is, however, no evidence that the early termination of federal benefits has led to an increase in hiring in these states. The government-funded benefits will expire on Sept. 6, affecting more than 11 million people.

“While states implementing an early termination argued that benefits were impeding labor supply, we only find a marginal effect,” said Gregory Daco, chief U.S economist at Oxford Economics in New York. “It appears the expiry of benefits will weigh more on the personal income ledger of the economy than it does to support employment growth.”

(Reporting by Lucia Mutikani; Editing by Chizu Nomiyama, Paul Simao and Andrea Ricci)