CHICAGO (Reuters) – The U.S. Department of Agriculture said on Sunday it will help fund a new container yard for agricultural exports at California’s Port of Oakland, as the government, ports and food companies scramble to ease costly shipping delays.

The multimillion-dollar project is set to open in March, and officials said it could be replicated elsewhere.

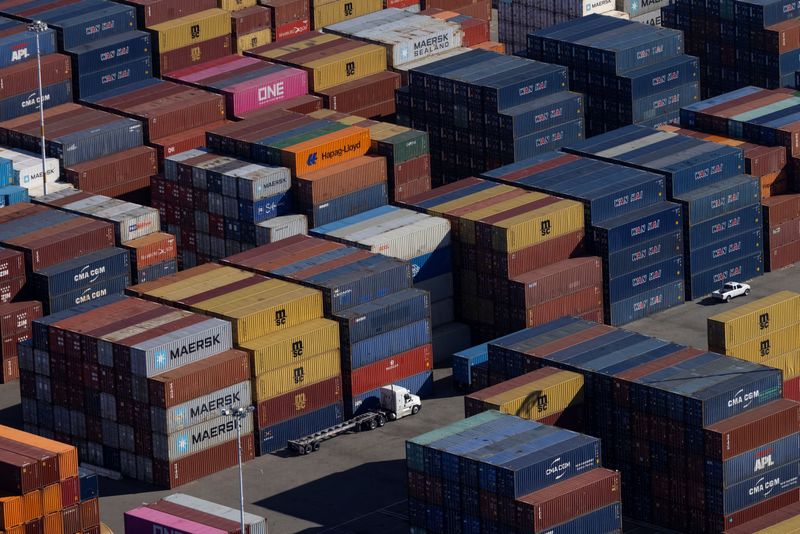

Strong U.S. demand for goods from Asia during the pandemic has boosted imports, clogging West Coast ports. Some ocean vessels have left the United States carrying empty containers after making deliveries, rather than waiting to fill ships with American goods for export.

Ships delivering cargo at ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach, California, have also skipped Oakland, a major hub for agricultural exports, to return to Asia more quickly.

Oakland’s export volume in 2021 declined 8% from the previous year, the port said, hurting shipments of products like nuts, dairy and produce.

“With the delays and disruptions that are occurring, market share is at risk,” U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack told Reuters.

The Port of Oakland will open a 25-acre acre “pop-up site” to provide space to prepare empty containers, the USDA said. The off-terminal site will move containers off chassis and store them for rapid pick up, the port said.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said in a statement that “inland pop-up ports” improved the flow of goods at the Port of Savannah and the government plans to work with other ports on similar ways to reduce congestion.

The USDA will pay 60% of the startup costs and partner with the Port of Oakland to partially cover a $125 per container reimbursement made to shippers, Vilsack said. The USDA estimated the project will cost about $5 million, and the port said the initial start-up will cost about $2 million.

“This is for however long it takes to get us back to a place where we have some stability in the market and some stability in the supply chain,” Vilsack said.

Though U.S. farm exports reached a record in 2021, they could have been bigger without delays at ports, Vilsack said.

In the first nine months of 2021, shipping disruptions cost the U.S. dairy industry about $1.3 billion due to lost business and higher shipping and storage costs, said Jaime Castaneda, executive vice president of the U.S. Dairy Export Council and National Milk Producers Federation.

Some importers canceled orders because of delays, forcing U.S. producers to resell their goods at a discount, Castaneda said.

Denver-based Leprino Foods, the world’s biggest mozzarella cheese maker, had 99% of its export shipments canceled or re-booked at least once last year, up from 10% in a typical year, Chief Executive Mike Durkin said.

Such delays contributed to a 57% surge in the company’s supply-chain costs last year, Durkin said. Costs are expected to jump another 50% in 2022, with a third of the increase related to exports, he said.

To deal with port delays, Leprino Foods trucked dairy products normally exported from Oakland to Houston and other ports, Durkin said. It also sent whey products via air to a customer in Asia that needed them to keep operations running, he said.

Durkin and dairy groups are working with the USDA, ports and shipping companies to improve exports.

“We’ve got to get this somehow figured out,” Durkin said. “The challenge is huge.”

(Reporting by Tom Polansek; Editing by David Gregorio)