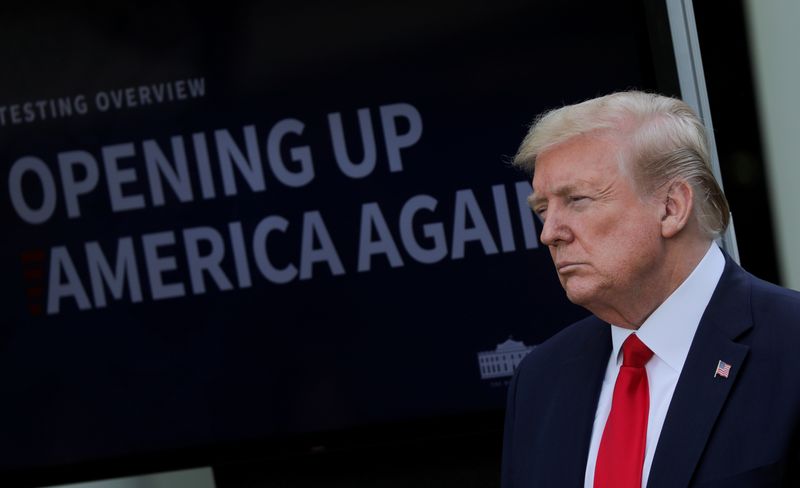

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. appeals court judges on Tuesday appeared skeptical about broad arguments made by the Trump administration that the House of Representatives cannot sue to enforce a subpoena demanding testimony of a former senior White House official.

Holding arguments by phone because of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit considered whether a House committee can sue in an effort to obtain testimony from former White House Counsel Donald McGahn.

The nine judges heard the case alongside another dispute between the House and the Trump administration over President Donald Trump’s announcement that he would spend $8.1 billion for a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border despite the fact Congress had appropriated only $1.375 billion.

Although the panel appeared generally sympathetic to the House’s arguments, some judges seemed concerned about opening the door to the House suing over all manner of issues, including policy disputes and military conflicts.

Courts are generally wary of weighing into such politically divisive issues, in the hope that a compromise will be reached.

Judge Judith Rogers appeared skeptical of the notion that courts cannot intervene when the executive branch and Congress are at odds. “Are you of the view there can be no role for the courts in terms of preserving the separation of powers?” she asked Hashim Mooppan, a Justice Department lawyer arguing for the Trump administration.

Judge David Tatel, referencing separate cases now at the Supreme Court concerning the House’s effort to obtain President Donald Trump’s financial records, questioned whether the Justice Department’s arguments are consistent. The Justice Department has said Trump can sue to block a subpoena but the House cannot sue to enforce one.

Judge Nina Pillard probed Mooppan on the scope of his argument that Congress can use political tools like withholding appropriations to force compliance with its subpoenas.

“I’m struggling to see how that theory applies” in the McGahn case because Congress has a long history of obtaining information from the executive branch, she added.

A divided three-judge panel of the court ruled for Trump in February, saying the court had no place in settling the closely watched dispute between the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government.

The panel of nine judges has a 7-2 majority of Democratic appointees. Two judges who were appointed by Trump to the court, Neomi Rao and Gregory Katsas, are not participating, likely because both previously worked in his administration.

The Democratic-led House Judiciary Committee has said the earlier 2-1 ruling upset the balance of powers created by the U.S. Constitution.

The committee had sought testimony from McGahn, who left his post in October 2018, about Trump’s efforts to impede former Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation that documented Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election.

McGahn declined to testify before the committee after the Trump administration advised him to defy the subpoena. The Justice Department, arguing for the Republican administration, has argued in court that senior presidential advisers are “absolutely immune” from being forced to testify to Congress about official acts and that courts lack jurisdiction to resolve such disputes.

The border wall case raises issues similar to the McGahn dispute, with a district court judge ruling that the House did not have standing to sue.

Addressing that case, one judge, Thomas Griffith, questioned whether the lawsuit could be brought by only the House and would also need to be joined by the Senate, the other chamber of Congress, to be successful.

(Reporting by Jan Wolfe and Lawrence Hurley; Editing by Peter Cooney, Jonathan Oatis and Dan Grebler)