WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. employment rose far less than expected in December amid worker shortages, and job gains could remain moderate in the near term as spiraling COVID-19 cases disrupt economic activity.

But the Labor Department’s closely watched employment report on Friday suggested the jobs market was at or near maximum employment. The unemployment rate tumbled to a 22-month low of 3.9% from 4.2% in November. The second straight big monthly decline occurred even as more people entered the labor force. Wages increased solidly, underscoring labor market tightness.

“The U.S. labor market may have lost a little momentum at the end of a stellar year, largely due to the lack of available workers rather than available positions, but it is holding up nicely, at least so far,” said Sal Guatieri, a senior economist at BMO Capital Markets in Toronto.

Nonfarm payrolls rose by 199,000 jobs last month, the survey of establishments showed. Data for November was revised up to show payrolls advancing by 249,000 jobs instead of the previously reported 210,000.

Economists polled by Reuters had forecast payrolls would rise by 400,000 and the unemployment rate to dip to 4.1%.

A record 6.4 million jobs were created last year. This was the largest annual increase in employment since record-keeping started in 1939, a milestone cheered by President Joe Biden, who celebrates his first anniversary in the White House on Jan. 20.

“I would argue the Biden economic plan is working,” Biden said at the White House. “And it’s getting America back to work, back on its feet.”

Still, employment is 3.6 million jobs below its peak in February 2020. With the jobless rate flirting with the pre-pandemic low of 3.5% and falling below the Federal Reserve’s longer-run estimate of 4.0%, some economists say the U.S. central bank could start raising interest rates in March.

“Most Fed officials will conclude that full employment has been reached, and we now expect liftoff in March and four hikes in 2022,” said Andrew Hollenhorst, chief U.S. economist at Citigroup in New York.

Minutes of the Fed’s Dec. 14-15 policy meeting published on Wednesday showed officials at the U.S. central bank viewed the labor market as “very tight.” (Graphic: Non-farm payroll, https://graphics.reuters.com/USA-ECONOMY/UNEMPLOYMENT/zjpqkyjzbpx/chart.png)

The underwhelming job growth in December likely reflects labor shortages as well as anomalies with the so-called seasonal adjustment, the model used by the government to strip out seasonal fluctuations from the data. There were 10.6 million job openings at the end of November.

December is typically a weak month for payrolls growth. Unadjusted payrolls increased by 72,000. The seasonal factor added 127,000 jobs to the December tally, less than the 213,000 added in December 2020 and fewer than the roughly 425,000 average prior to the pandemic.

“The seasonal factor added about 300,000 less than in the pre-COVID years,” said Jim O’Sullivan, chief U.S. macro strategist at TD Securities in New York. “I’m not saying you necessarily should add 300,000, but it does look like a pretty extreme factor.”

Employment was unlikely to have been impacted by surging infections driven by the Omicron variant of COVID-19. The government surveyed businesses and households for last month’s report in mid-December just as Omicron was barreling across the country. The variant’s hit to payrolls could be felt in January.

The average workweek was unchanged at 34.7 hours.

Stocks on Wall Street were mixed. The dollar fell against a basket of currencies. U.S. Treasury yields rose.

STRONG DETAILS

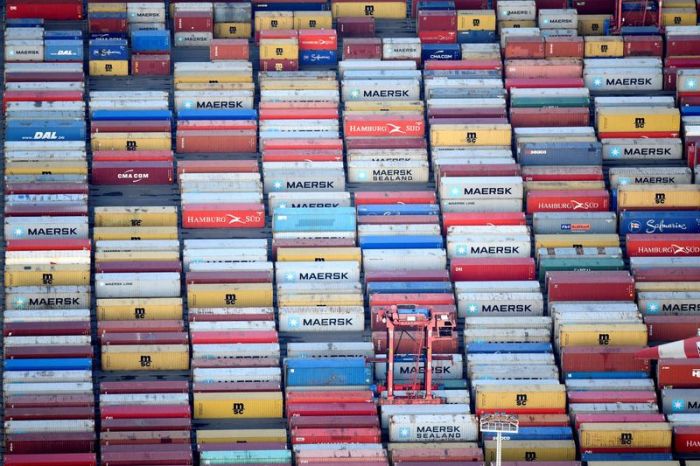

Job gains last month were led by the leisure and hospitality sector, which added 53,000 positions. Professional and business services payrolls rose by 43,000 jobs. Manufacturing added 26,000 jobs, while construction employment rose 22,000.

There were also gains in transportation and warehousing as well as wholesale trade and mining. Government employment fell by 12,000 jobs. Retail payrolls dropped as did those for utilities. (Graphic: Jobs by industry, https://graphics.reuters.com/USA-FED/INDUSTRY/qmypmdoolvr/chart.png)

The United States reported nearly 1 million new coronavirus infections on Monday, the highest daily tally of any country in the world. Airlines have canceled thousands of flights and some school districts have suspended in-person learning.

Some working parents may have to take on childcare duties, with the reversion to online learning. People who are out sick or in quarantine and do not get paid during the payrolls survey period are counted as unemployed even if they still have a job.

There are more signs of unemployed people stepping back into the labor market following the end of supplemental government-funded jobless benefits early in the fall. But the reentry could be slowed by soaring Omicron cases.

The survey of households, from which the unemployment rate is derived, showed 168,000 people entered the labor force. The workforce has now increased for a third straight month, though it remains 2.2 million jobs below its pre-pandemic level.

The household survey also showed an increase of 651,0000 in employment, which accounted for the three-tenths-of-a percentage-point drop in the unemployment rate. There were fewer people working part-time for economic reasons and there was a big drop in those reporting that they could not work because of the pandemic. (Graphic: Unemployment rate, https://graphics.reuters.com/USA-ECONOMY/UNEMPLOYMENT/gdpzymqoqvw/chart.png)

Still, the labor force participation rate, or the proportion of working-age Americans who have a job or are looking for one, was unchanged at 61.9%. It remains well below the 63.4% rate before the pandemic. The employment-to-population ratio, viewed as a measure of an economy’s ability to create employment, rose to 59.5% from 59.3% in November.

Tightening labor market conditions were highlighted by a solid 0.6% jump in average hourly earnings last month after a rise of 0.4% in November. The annual increase, however, fell to a still-high 4.7% from 5.1% in November. This is the result of last year’s big gains falling out of the calculation.

Though inflation has outpaced wage gains, many consumers have continued to spend because of massive savings and increased job security, underpinning the economy. Growth last year is expected to have been the strongest since 1984.

(Reporting by Lucia Mutikani; Editing by Dan Burns, Chizu Nomiyama and Paul Simao)