(Reuters) – U.S. support for waiving intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines could be a tactic to convince drugmakers to back less drastic steps like sharing technology and expanding joint ventures to quickly boost global production, lawyers said on Thursday.

“I think the end result that most players are looking for here is not IP waiver in particular, it’s expanded global access to the vaccines,” said Professor Lisa Ouellette of Stanford Law School.

President Joe Biden on Wednesday supported a proposal to waive World Trade Organization intellectual property (IP) rules, which would allow poorer countries to produce vaccine for themselves. So far COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed primarily to the wealthy countries that developed them, while the pandemic sweeps through poorer ones, like India.

The real goal, though, is expanded vaccine distribution.

“If it is possible to increase the rate of scaling up production, this potentially would give the manufacturers a greater incentive to come to an agreement to make that happen,” Ouellette said.

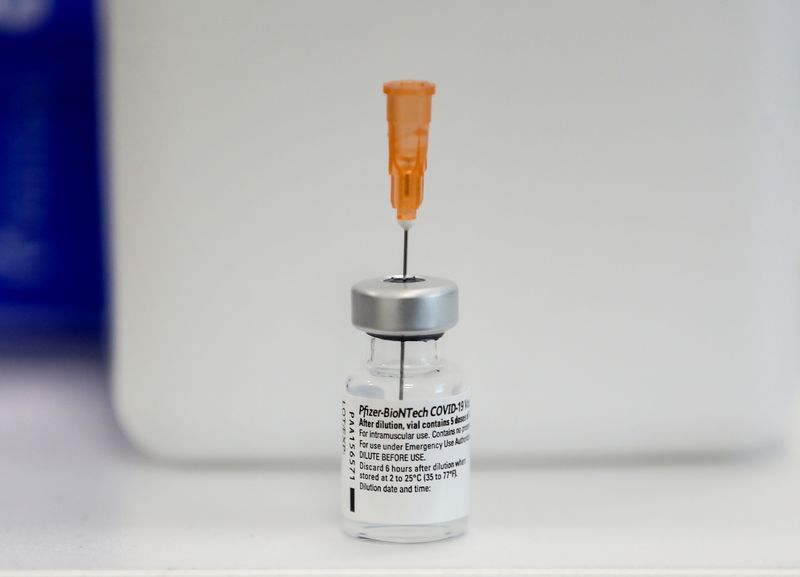

Vaccine makers like Moderna, Pfizer and BioNTEch have argued that patents have not been a limiting factor in supply. New technology and global limits on supplies are frequently cited as challenges, and both Moderna and Pfizer nevertheless have steadily boosted supply forecasts.

“There is no mRNA in manufacturing capacity in the world,” Moderna Chief Executive Stephane Bancel said on a conference call with investors on Thursday, referring to the messenger RNA technology behind both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccine.

“This is a new technology. You cannot go hire people who know how to make the mRNA. Those people don’t exist. And then even if all those things were available, whoever wants to do mRNA vaccines will have to buy the machine, invent the manufacturing process, invent verification processes and analytical processes.”

To increase vaccine production capacity significantly within two years, the Biden administration would need to do much more than waive patents, including providing funding to find and build new manufacturing sites, and backing technology and expertise transfer to the new manufacturers, said drug supply chain expert Prashant Yadav.

Moreover, the U.S. government must guard against allowing foreign companies to use COVID-19 vaccine makers’ technology to compete in areas outside of COVID-19, which are likely to be more lucrative in the long term, said Thomas Kowalski, an attorney at Duane Morris who specializes in intellectual property. Once a competitor has the technology, restrictions on use are difficult to enforce, he said.

Professor Sarah Rajec of William & Mary Law School said she did not think a waiver itself would do as much as the signal from the United States, a stronger supporter of corporate intellectual property, that patent rights take a backseat to the urgent needs of the world population during the pandemic.

Rajec said Biden’s support for a waiver “pushes the drug companies to be more open to partnerships, and other licensing on favorable terms, in a way that perhaps they otherwise wouldn’t be.”

Drugmakers argue that they have already struck significant partnerships, sharing technology with competitors who they might not have linked up with if not for the pandemic.

“Our position is very clear: this decision will further complicate our efforts to get vaccines to people around the world, address emerging variants and save lives,” Brian Newell, spokesman for pharmaceutical industry group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America said in a statement.

European patent attorney Micaela Modiano said that even if the waiver is adopted, vaccine makers are likely to negotiate for some payment, if less than what is generally paid in licensing arrangements. Her firm Modiano & Parners represents Pfizer but has not worked on any COVID-19 related matters.

“I would imagine that the pharmaceutical companies are already and will continue to lobby significantly to make sure that if this waiver proposal passes, that it just doesn’t pass as such, but that they receive some sort of financial compensation,” she said.

(Reporting by Michael Erman in Maplewood, N.J. and Blake Brittain in Washington, D.C.; additional reporting by Carl O’Donnell in New York; editing by Caroline Humer, Peter Henderson and David Gregorio)