WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Americans are growing increasingly aware of racial inequality in the United States, but a large majority still oppose the use of one-time payments, known as reparations, to tackle the persistent wealth gap between Black and white citizens.

According to Reuters/Ipsos polls this month, only one in five respondents agreed the United States should use “taxpayer money to pay damages to descendants of enslaved people in the United States.”

Calls are growing from some politicians, academics and economists for such payments to be made to an estimated 40 million African Americans, amid an expanding discussion about race in America. Any federal reparations program could cost trillions of dollars, they estimate.

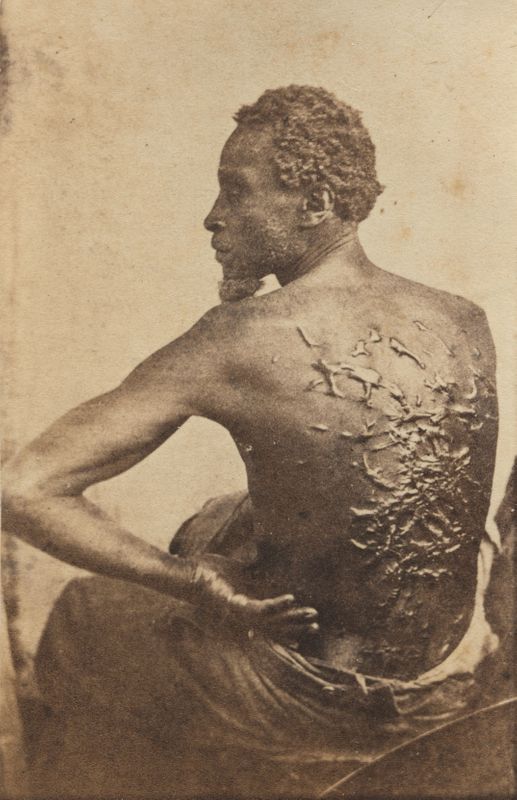

Supporters say such payments would act as acknowledgement of the value of the forced, unpaid labor that supported the economy of Southern U.S. states until the Civil War ended slavery in 1865, the broken promise of land grants after the war and the burden of the century and a half of legal and de facto segregation that followed.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted on Monday and Tuesday showed clear divisions along partisan and racial lines, with only one in 10 white respondents supporting the idea and half of Black respondents endorsing it.

Republicans were heavily opposed, at nearly 80%, while about one in three Democrats supported it. The poll did not ask respondents why they answered the way they did. Other critics have said too much time has passed since slavery was outlawed, and expressed confusion about how it would work.

“I’m not racist and think it’s an insult for someone to pay me or anyone else strictly based on the color of their skin,”

Burgess Owens, a retired National Football League player and a Republican candidate for Congress from Utah, told Reuters on Wednesday.

‘WHAT DO THEY MEAN?’

“Those who say they care about slavery should be leading the charge to save the 30 million men, women and children enslaved today around the world” by sex trafficking and other evils, said Owens, an African American.

Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell criticized the idea last year, saying that “none of us currently living are responsible” for slavery, which he calls America’s “original sin.”

Asked about reparations during a 2019 Democratic presidential debate, progressive Senator Bernie Sanders asked: “What does that mean? … I don’t think anyone’s been very clear.”

On Wednesday, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard said: “To promote racial economic equity, we as a nation must consider structural or institutional responses.”

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has said he would support a commission studying the feasibility of the idea. Some local governments and academic institutions are starting https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-race-reparations-feature-trfn/calls-for-reparations-gain-steam-as-us-reckons-with-racial-injustice-idUSKBN23V2UO programs of their own, and Democratic Representative Sheila Jackson Lee said another hearing on the issue would occur in Congress this year.

“Doubters may not have had slaves yesterday, or a decade ago or 100 years ago, but any wealth they hold or expect to gain only exists because of the institution of slavery,” Jackson Lee told Reuters.

Reparations have been used in other circumstances to offset large moral and economic debts – paid to Japanese Americans interned during World War Two, to families of Holocaust survivors in Germany and to Blacks in post-apartheid South Africa.

Formal proposals in the United States have been more narrowly cast, such as using existing social programs, for example, but increasing the amount of support for those who live in areas of persistent poverty.

U.S. SHIFTS ON RACE

The mood surrounding racial issues may be shifting, Reuters polls showed, with more Americans agreeing with the idea that Black people are still treated unfairly, and supporting the specific complaints about police behavior raised by groups like Black Lives Matter.

Seventy-two percent of Reuters/Ipsos poll respondents in a survey last week said they understood “why Black Americans do not trust the police,” up 17 points from a similar poll in May 2015. Fifty-nine percent of Americans said police were too violent when handling people suspected of crimes, up 15 points from a similar poll in July 2016.

The polls were conducted after the May 25 death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody ignited national and international protests against police brutality and racial injustice.

The economic crash caused by the coronavirus pandemic has also focused attention on gaps in economic outcomes between Black and white Americans, despite decades of efforts to prevent discrimination in hiring, housing and education.

Black adults have been hit harder by job losses in recent months, reversing recent progress in closing the roughly 2-1 gap in unemployment rates with white Americans – a racial wedge that has existed for as long as joblessness has been calculated.

Median income for Black families is about 57% that of white ones, a gap that compounds over time into dramatic differences in wealth as well.

The failure of efforts to offset inequality, beginning with broken promises of farmland for freed slaves after the Civil War, “laid the foundation for the enormous contemporary gap in wealth between Black and White people in the U.S.,” Duke University economist William Darity and writer A. Kirsten Mullen argued in their April book “From Here to Equality.”

The latest Reuters/Ipsos poll surveyed 1,115 adults about their feelings on slavery reparations and asked 4,426 adults about racial issues in a separate poll that ran June 10 to 16. The polls had a credibility interval, a measure of precision of between 2 and 3 percentage points.

(Reporting by Katanga Johnson; Additional reporting by Howard Schneider and Chris Kahn; Editing by Heather Timmons and Peter Cooney)