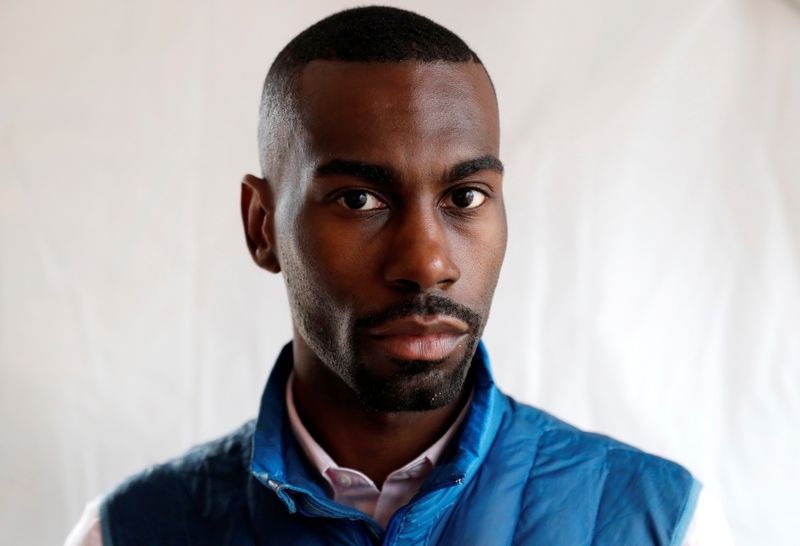

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday sided with Black Lives Matter activist DeRay McKesson in his ongoing effort to avoid a lawsuit filed by a police officer injured during a 2016 protest in Louisiana triggered by the police killing of a Black man.

The justices threw out a lower court ruling that had allowed the lawsuit to proceed and said that more analysis was needed on whether Louisiana state law allows for such a claim.

McKesson has argued that the rights of freedom of speech and assembly under the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment should shield him from the lawsuit that accused him of negligence for leading the protest in Baton Rouge, but the court did not resolve that issue.

“The constitutional issue, though undeniably important, is implicated only if Louisiana law permits recovery under these circumstances in the first place,” the court said in the unsigned ruling.

The officer sustained serious injuries after being struck in the face by a rock or piece of concrete thrown by an unknown person, not by McKesson.

Litigation will now continue in lower courts.

Conservative Justice Clarence Thomas dissented and newly appointed Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not participate, the ruling said.

The officer, whose identify was not disclosed in the lawsuit, sued the Black Lives Matter organization and McKesson seeking monetary damages over an incident at a July 2016 protest in Baton Rouge. The negligence lawsuit argued that McKesson should have known that violence would result from his actions leading the protest, which was one of many around the country that year arising from incidents involving police and Black individuals.

The protest took place outside the police department in the aftermath of the police killing of Alton Sterling, a Black man, after a struggle outside a convenience store where he was selling homemade CDs. The incident was caught on video.

McKesson, a civil rights activist who was one of the leading voices in the Black Lives Matter movement, said that his First Amendment rights outweigh any potential liability for negligence he could face under Louisiana law.

His lawyers said that if protest organizers can be sued for actions taken by others without their involvement, it could enable opponents to effectively block future demonstrations because activists would have to direct resources to battling litigation and could face monetary damages at trial.

McKesson’s lawyers, including the American Civil Liberties Union, have cited a 1982 Supreme Court ruling involving Black civil rights activists in Mississippi that limited liability for protest leaders over the conduct of others when they are involved in actions protected by the First Amendment.

The officer, according to the lawsuit, suffered loss of teeth, a jaw injury, a brain injury and a head injury.

The Black Lives Matter movement was formed after the high-profile killing of a Black 17-year-old named Trayvon Martin by a man named George Zimmerman in Florida in 2012. Its activists have criticized overly aggressive policing particularly against Black Americans. The movement attained further prominence following the May police killing of a Black man named George Floyd in Minneapolis.

In 2017, a federal judge ruled that neither McKesson nor the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole could be sued over the Baton Rouge incident.

The officer appealed and in 2019 the New Orleans-based 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals revived the claim against McKesson, who then appealed to the Supreme Court. The 5th Circuit left in place the judge’s ruling dismissing Black Lives Matter from the case.

(Reporting by Lawrence Hurley; Editing by Will Dunham)