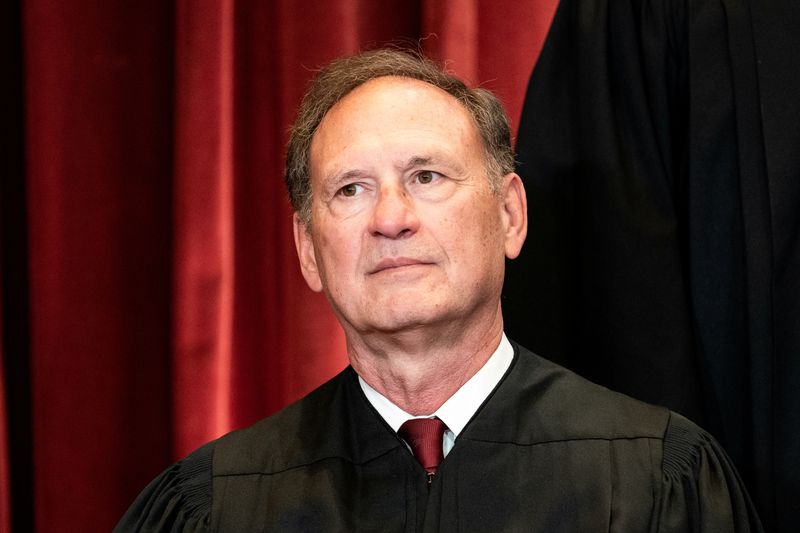

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Justice Samuel Alito’s draft U.S. Supreme Court ruling that would overturn the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion nationwide hinges on a contested historical review of restrictions on the procedure enacted during the 19th century.

Lawyers and scholars backing abortion rights have criticized Alito’s reading of history as glossing over disputed facts and ignoring relevant details as the conservative justice sought to demonstrate that a woman’s constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy was wrongly recognized in the Roe ruling.

Conservatives who oppose abortion rights have praised Alito’s opinion and argued that the Roe decision itself was based on a faulty reading of history.

The unprecedented leak this week of the draft before the nine justices have finalized their decision – due by the end of June – has given critics a chance to scrutinize a work in progress, hoping other justices will have second thoughts about joining Alito, thus changing the outcome of the momentous case.

Alito’s draft would uphold a Republican-backed Mississippi law – struck down by lower courts as a violation of the Roe precedent – banning abortions at 15 weeks of pregnancy.

His reasoning was that a right to abortion was not “deeply rooted in this nation’s history.” Alito relied upon a reading of state laws on the books in 1868 when the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment, which among other things protects due process rights, took effect in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. Civil War and the end of slavery.

The Roe ruling found that the right to abortion arises from the 14th Amendment’s protection of due process rights, which the Supreme Court has found safeguards a person’s right to privacy.

To Alito, the scope of 14th Amendment rights must be considered in the context of the times in which it was devised. Alito wrote in his draft that when the 14th Amendment was ratified to protect the rights of former slaves, 28 of the then-37 U.S. states “had enacted statutes making abortion a crime” even early in a pregnancy. This shows, Alito argued, that there was no understanding at the time of any right to abortion.

Some lawyers who support abortion rights said many states lacked criminal abortion restrictions until the mid-19th century and some banned it only when performed at a point later in a pregnancy – known as “quickening” – when the woman could feel the fetus move, usually at four to five months of gestation.

‘MISSING THE NUANCE’

Tracy Thomas, a professor at the University of Akron School of Law in Ohio, said Alito selectively cited history as presented by anti-abortion activists.

“We do have to interpret history, but we also have to see the nuance, and he is missing the nuance,” said Thomas, who favors abortion rights.

A brief filed in the case by groups representing historians supportive of abortion rights said that in 1868 “nearly half of the states continued either not to prohibit abortion entirely or to impose lesser punishments for abortions prior to quickening.”

Even in places where all abortions were banned, “ordinary citizens continued to believe that not all abortions were criminal and that women held the power to determine whether to terminate a pregnancy,” the brief said.

University of California, Davis School of Law professor Aaron Tang has argued that state laws enacted in the 19th century were not understood to ban abortion before quickening.

“There are huge risks trying to answer this 2022 question based on what happened in 1868,” Tang said.

Conservative scholars reject the idea that there was ever an implicit right to abortion. In a brief filed in the case, Princeton University’s Robert George, who opposes abortion rights, called it a “preposterous claim” and criticized the Roe ruling for relying on the work of the late scholar Cyril Means, an abortion rights supporter whose work Alito specifically rejected.

Some experts who back abortion rights said it is irrelevant what state laws were on abortion more than 150 years ago.

The Supreme Court has faced accusations of a selective reading of history before, notably when it found in 2008 that the Constitution’s Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms included an individual’s right to own a weapon for self-defense in the home.

The late Justice John Paul Stevens, who dissented in that case, later wrote of his disappointment of how the court’s majority handled the historical record, calling the ruling “the worst self-inflicted wound in the court’s history.”

David Garrow, a legal historian, said lawyers on both sides of the abortion debate have disregarded the practical reality that the procedure was commonplace even in states where it was banned when the 14th Amendment was added and that criminal prosecutions were rare.

“If you wanted to argue that abortion is deeply rooted in American history you don’t argue about state statutes,” Garrow said. “You argue about the evidence of demographic reality.”

(Reporting by Lawrence Hurley; Editing by Will Dunham and Scott Malone)