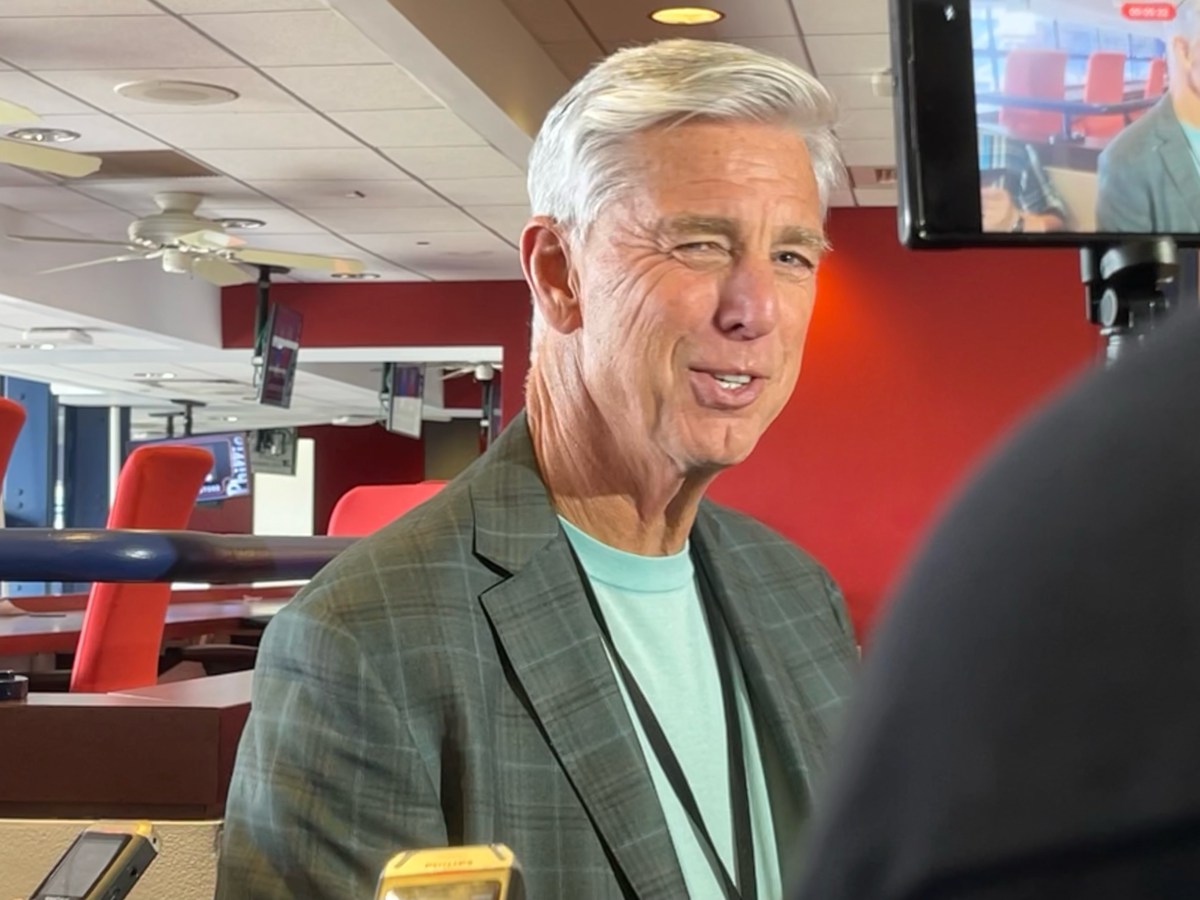

STAMFORD, Connecticut (Reuters) – Timothy Kane, CEO of Goodway Technologies Corp, has never been so popular. Making machines that spray disinfectant, once a niche business, is now an essential service – and the phone is ringing off the hook.

“Our orders jumped 50-fold in April, it was like a switch got flipped,” said Kane.

Goodway, which has a factory in Stamford, Connecticut, builds machines that spray an alcohol-infused mist to sanitize surfaces. Until a few months ago, those devices were just a tiny part of its business, catering mostly to places like industrial bakeries that had to constantly clean surfaces.

Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic grips the United States, everyone wants one.

Kane, who employs 110 workers in the family-owned company, has fielded calls from hotels, gyms and casinos, as well as factories and warehouses. Many would previously never have thought they needed such machines, which often look much like souped-up vacuum cleaners.

The rise of this industry is one example of a sector that is booming during a pandemic that has laid waste to so many parts of the economy.

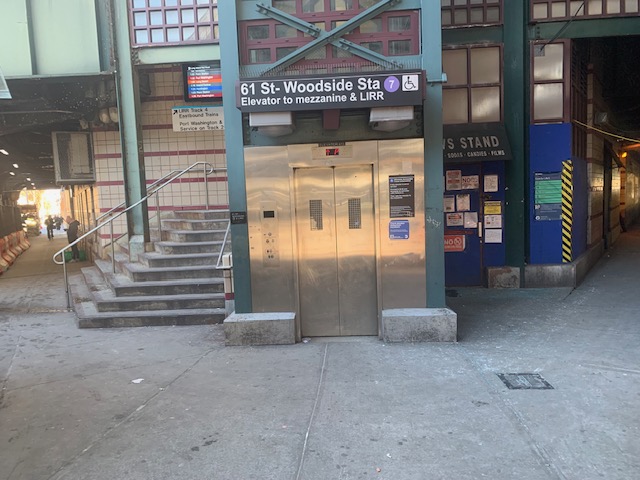

America’s battle against the novel coronavirus is driving demand for everything from hand sanitizer and masks to thermometer guns and plexiglass. But one enduring image of this crisis may be the foggers and spraying machines that are now being set loose in airports, sports arenas and subways.

Yvon Brunache bought a Goodway sprayer to help his Florida construction business because clients fearing COVID-19 were reluctant to have his team in their buildings. “My customers are asking more and more for the space to be sanitized,” he said.

The surge of business is, however, putting strain on producers that never envisaged such a situation and their supply chains.

Victory Innovations, another maker of hi-tech spray machines, is sold out through September. Its shipments have surged 10-fold since the start of the pandemic, to about 100,000 units a month, according to the company, based in Eden Prairie, Minnesota.

ROBOT FLEET

Servpro Industries LLC has completed 10,000 coronavirus-related deep cleaning operations in the last 90 days, according to Chief Operating Officer John Sooker.

“We’ve always done biohazard cleaning, but never at this scale.”

Servpro, based in Gallatin, Tennessee, is majority owned by the Blackstone Group <BX.N> and runs franchised cleaning businesses across the United States and Canada.

The company, which had sales of about $3 billion last year, figures biohazard cleaning – such as sanitizing a cruise ship after an outbreak of illness – constituted only about 5% of its business then, or $150 million.

Sooker said he expects COVID-19-related cleaning alone to bring in at least $250 million to $300 million this year.

The crisis is sparking innovation.

Albuquerque’s airport has just introduced a fleet of four robots, each about the size of a small trash can on wheels, which trundle around the terminals every night spraying a disinfectant mist.

“It costs a fraction of what it would cost to have a team of people doing it,” said Kimberly Corbitt, chief commercial officer of Build With Robots, one of the machines’ developers, although she declined to reveal the cost.

The airport emphasized that none of its janitors would get laid off as a result, since the fogging is an added layer of overnight cleaning.

FLAMETHROWER

Sophisticated spraying machines don’t come cheap, though, even the less automated ones; a small human-operated sprayer mounted in a backpack can set you back about $5,000.

Biomist Inc., a manufacturer in Wheeling, Ill., has installed spraying systems custom-designed for a facility that cost over $50,000, said Robert Cook, a vice president.

Goodway, meanwhile, has doubled the number of models it is selling to six, creating designs tailored to specific uses such as restaurants and health clubs.

Workers at its factory can be seen hunched over a row of curved stainless-steel machines mounted on wheels being built on the production floor.

CEO Kane said there were many ways to spray disinfectants, and that the process could be surprisingly complex, and even potentially dangerous.

Some machines use water-based cleansers, which take time to dry or must be followed by people wiping the surfaces. Other devices, like those made by Goodway, mix alcohol – which dries almost instantly – with the same chemicals used in fire extinguishers, Kane said.

“If you don’t do it right, you can end up with a flamethrower.”

(Reporting by Timothy Aeppel; Editing by Pravin Char)