(Reuters) – Gilead Sciences Inc <GILD.O> faces a new dilemma in deciding how much it should profit from the only treatment so far proven to help patients infected with the novel coronavirus.

The drugmaker earned notoriety less than a decade ago, when it introduced a treatment that essentially cured hepatitis C at a price of $1,000 per pill.

Public outrage over the cost of Sovaldi in 2013 – despite that it was a vast improvement over existing equally expensive therapies – ignited a national debate on fair pricing for prescription medicines that the pharmaceutical industry has fought to deflect ever since.

That backlash has subsided considerably in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, during which drugmakers’ efforts to develop vaccines and treatments is considered essential to battling a disease that has infected some 3.7 million people and killed over 258,000 worldwide.

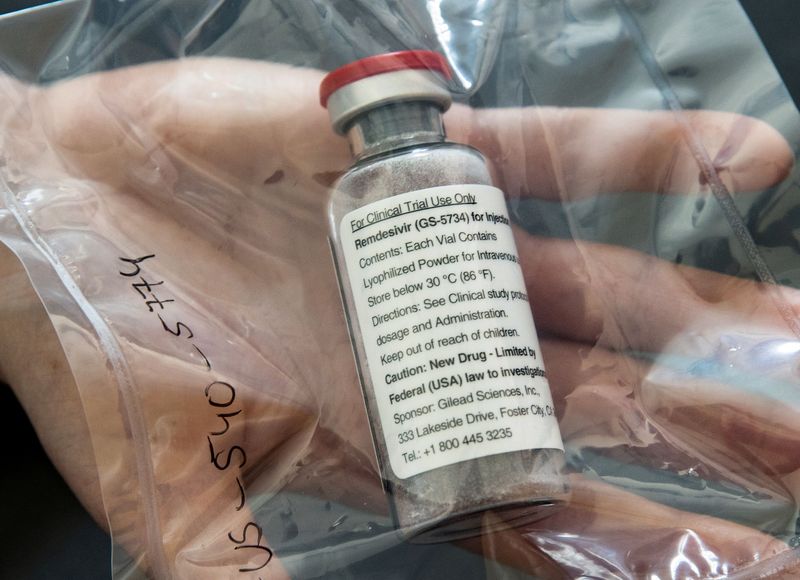

Gilead is now in the spotlight again after data showed its antiviral drug remdesivir helped reduce hospital stays for COVID-19 patients, and the U.S. authorized wide emergency use of the therapy.

Wall Street analysts say remdesivir could generate $750 million or more in worldwide sales next year, and $1.1 billion in 2022, assuming the pandemic continues. But Gilead, and other drugmakers, will need to avoid the appearance of taking advantage of a global health crisis to rake in profit, according to pharmaceutical industry consultants and former regulators.

“This is a tremendous opportunity for drug manufacturers,” to improve the industry’s image, said Ed Schoonveld, a drug pricing expert at consulting firm ZS Associates. “There has been an overwhelmingly negative focus on drug prices.”

Gilead Chief Executive Daniel O’Day, in the post just over a year, is proceeding with caution. The company is donating enough remdesivir for at least 140,000 patients for distribution by the U.S. government to hospitals nationally.

At a meeting with President Donald Trump in the White House on Friday, O’Day pledged to make the therapy available to those in need.

Gilead also aims to increase worldwide manufacturing to supply over a million coronavirus patients by year-end, rising to several million in 2021, if required. The company has not disclosed its pricing plans.

“I think this will certainly help the industry’s reputation,” O’Day said on a recent conference call with investors. “I’m not suggesting that there won’t continue to be focus and pressure on drug pricing … but it’s being done now in a way where we can have an appreciation for the innovation the industry brings.” Gilead on Tuesday said it was talking with chemical and drug manufacturers to produce remdesivir for Europe, Asia and the developing world through at least 2022. The company said it was negotiating voluntary licenses with generic drugmakers in India and Pakistan, who would produce a lower-cost supply of remdesivir for developing countries.

FEDERAL MARCH IN?

Estimates of a fair price for remdesivir in the United States, where drugmakers generally charge the most for a new therapy, vary widely.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), which assesses effectiveness of drugs to determine appropriate prices, suggested a maximum price of $4,500 per 10-day treatment course based on the preliminary evidence of how much patients benefited in a clinical trial. Consumer advocacy group Public Citizen on Monday said remdesivir should be priced at $1 per day of treatment, since “that is more than the cost of manufacturing at scale with a reasonable profit to Gilead.”

Some Wall Street investors expect Gilead to come in at $4,000 per patient or higher to make a profit above remdesivir’s development cost, which Gilead estimates at about $1 billion.

Gilead shares have risen about 20% since the beginning of the year, largely on hopes for remdesivir. That compares with a drop of 12% for the broad S&P500 Index.

Some experts warn that a much higher U.S. price for remdesivir would put Gilead back in the crosshairs on drug pricing. In a more extreme scenario, the company could risk federal or state government action to march in and invalidate the medicine’s patent protection in the name of public health and issue mandatory manufacturing orders.

The U.S. government has never invoked those rights. But it has sued Gilead over patents on two of its widely-used HIV drugs that received federal funding grants while in development.

“If there is ever a time when those issues might arise, this would be that time,” said Eric Katz, CEO at consulting firm HealthTech GPS, which advises the industry on pricing.

Katz, a former official at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said the government could make similar arguments over remdesivir, which was originally developed to treat Ebola with federal funding, and is now being studied in a trial backed by the National Institutes of Health.

Democratic lawmaker Lloyd Doggett of Texas, chairman of the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, sent Gilead a letter this week demanding the company detail its plans for remdesivir, including supply issues, disclosure of taxpayer investment in the drug’s development, and purchase and pricing arrangements. “American taxpayers have made a big investment in remdesivir, but now in return, those who need treatment may get only a big bill while Gilead gets a big payoff,” Doggett warned.

(Reporting By Deena Beasley; Editing by Michele Gershberg and Bill Berkrot)