CIUDAD JUAREZ, Mexico (Reuters) – Lear Corp is implementing costly safety measures that may hurt productivity at its operations in Mexico after suffering the deadliest known factory-related coronavirus outbreak in the Americas, but the U.S. auto parts maker still faces a battle to win back workers’ trust.

The northern Mexican border city of Ciudad Juarez remains in the throes of the pandemic as it mourns the deaths of numerous factory workers, including 20 from Lear’s <LEA.N> Rio Bravo plant, which makes trim seat covers for Mercedes-Benz and Ford.

“I don’t think you’ll find anyone who says they’re not scared,” Alma Sonia Trevizo, an employee at the Rio Bravo plant, told Reuters while on a break from safety training ahead of its planned June 1 partial restart.

Following one-way arrows along hallways, eating at cafeteria tables with tall dividers, and stamping shoes on a mat soaked in disinfectant are among the new measures being adopted.

“But we have to take the first step and go on,” Trevizo said, adding that she was urging colleagues not to be fearful.

With no clear answers about how the virus spread in the plant, many workers fear going back, but they need the money, three employees told Reuters anonymously.

The company has not disclosed the names of the workers who died in the outbreak, which is believed to have been the worst to occur in any factory in the Americas.

New signs in the plant with reminders to wash hands regularly and report symptoms do not acknowledge the deaths.

“I’m scared to return. You feel a horrible chill entering the plant,” one worker said.

Mexico has one of the world’s worst coronavirus outbreaks, ranking seventh in the number of deaths from COVID-19, the respiratory illness caused by the virus. But it has come under U.S. government and industry pressure to reopen quickly to protect deeply intertwined supply chains, which last year fueled $614.5 billion in trade.

Lear’s efforts to protect workers amid the ongoing outbreak do not come cheaply and will affect productivity, said Sergio Corral, the Rio Bravo plant manager.

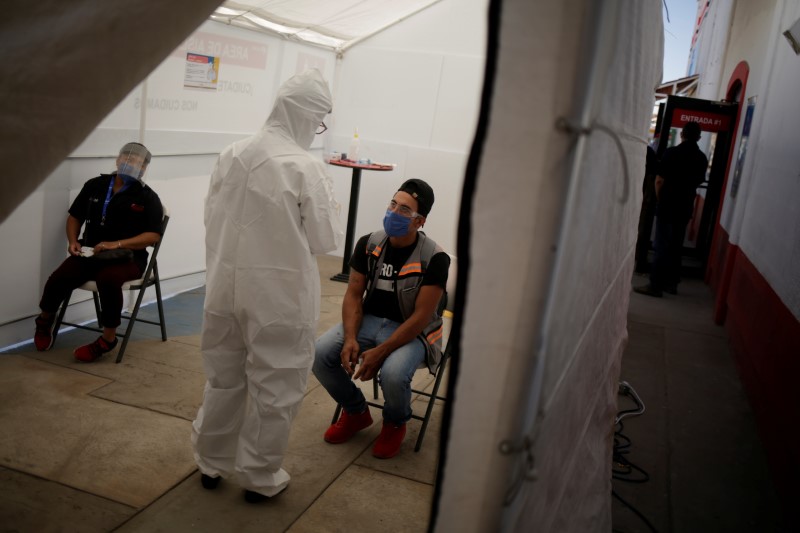

The entrance screening alone could take up to an hour for a single shift: Workers must snake through a single-file line, show identification, have their temperatures taken, and say whether they have shown any symptoms or been in contact with anyone with the coronavirus.

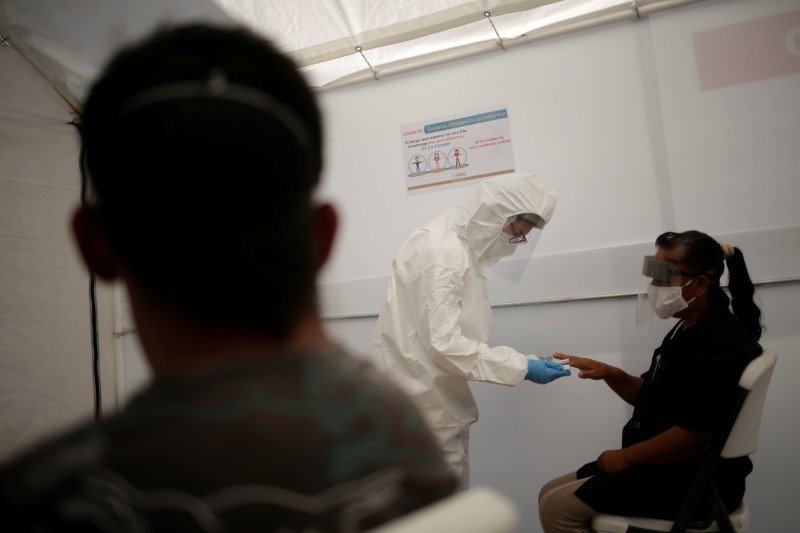

Anyone with a high temperature would be whisked into an “isolation” tent, shielded from the sun, for a recheck.

Corral said he expects productivity to drop 30% to 40%; a commitment to testing all 3,000 staff, if they request it, could cost $450,000; and the company has vowed to shutter factories for deep cleaning every time it finds a confirmed infection.

As well, with commuter buses now only half full to provide more space, Lear will need to hire others or send drivers on extra trips to bring in an entire shift.

Only about 15% of staffers will work at first, with others gradually joining, so that bosses can carefully supervise.

Some employees, dubbed “sentinels,” will monitor co-workers for violations such as a hug or kiss on the cheek, or simply standing too close to another person.

“The problem comes in practice. It happens to everyone – you start to talk, you can’t hear, so you get closer and closer, until you’re not at a safe distance,” Corral said.

MASKS, PEDALS AND DIVIDERS

During a tour on Wednesday, executives swung their arms open to remind others to stay back. They spoke loudly to be heard through white masks made by Lear in the Dominican Republic that, along with glasses or a face shield, are mandatory for workers.

Tall cubicle walls now separate hundreds of sewing machines, meaning workers may be able to hear, but not see or touch, their colleagues. Hand-sanitizer dispensers and water fountains have been outfitted with pedals so that workers touch as few surfaces as possible.

Lear’s vice president for global trim operations, Oscar Dominguez, recognized that fear runs higher in Rio Bravo than at Lear’s 41 other plants in Mexico. Just under half of Lear’s 56,000 Mexican employees are in Ciudad Juarez.

Dominguez said Lear analyzed infections among workers but was unable to detect how the virus spread.

“It’s something that unfortunately couldn’t be prevented because we never knew what was happening,” he said. “Our most heartfelt condolences for all these families.”

Of the 20 workers who died, two of them reported symptoms about a month after they stopped coming in to work, Dominguez added.

Ten workers in the Rio Bravo plant previously told Reuters that Lear took minimal protection measures before halting production in late March, a month after Mexico detected its first cases.

Jose Luis Salazar, Lear’s North America environment, health and safety director, said he hoped the new measures would give workers confidence that they will be protected on site.

“Even much better than outside, or where they live,” he said.

Some workers said the plant’s transformation had gradually put them at ease.

“The first day, I can’t deny it, I was scared,” said Jose Roman Diaz, a maintenance worker who was one of the first to return to the plant after the outbreak. “But over time, I was able to adapt.”

(Reporting by Daina Beth Solomon, Additional reporting by Jose Luis Gonzalez; Editing by Paul Simao)