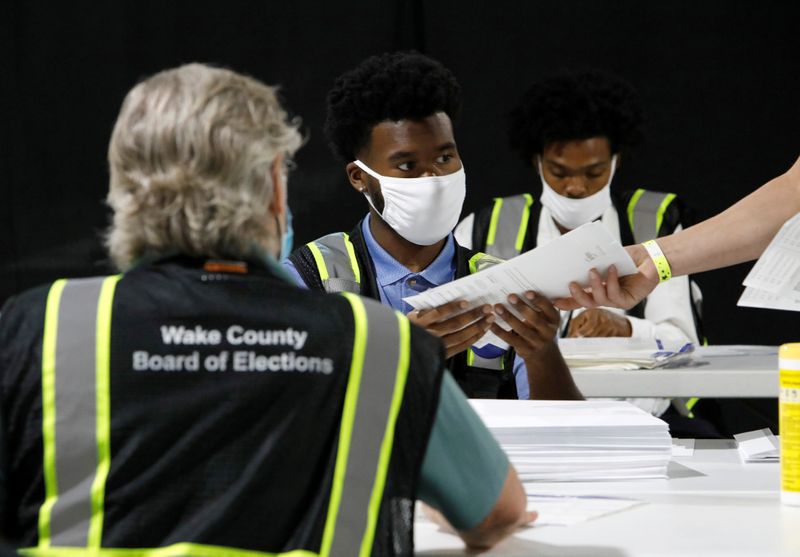

(Reuters) – After scrambling to replace an aging force of poll workers most at risk from the coronavirus, U.S. election officials face the challenge of running the Nov. 3 voting with untested volunteers tasked with following strict health protocols in an intensely partisan environment.

A nationwide drive that recruited hundreds of thousands of younger poll workers – the people who set up equipment, check in voters and process ballots – means most battleground states will not be understaffed, a Reuters review of Florida, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin found.

In nearly all of those states, more poll workers have already been recruited than worked the 2016 presidential election, according to data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, state election officials and private poll worker recruitment campaigns. Wisconsin did not have complete data.

The new poll workers must be trained not only in the usual election tasks but also issues uniquely relevant in 2020, such as how to handle voters who violate COVID-19 safety rules and ways to de-escalate political confrontations.

In a year that has seen armed militia members confront protesters, some voting rights advocates worry gun-toting groups will show up outside polling places.

They are also concerned by a highly unusual drive by Republicans to deploy thousands of poll watchers as part of efforts to find evidence to support President Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated complaints about widespread voter fraud.

Though more than 20 million Americans have already cast ballots and many others still expect to vote early in person or by mail, roughly a third to almost half of voters in critical battleground states plan to vote on Nov. 3, according to Reuters/Ipsos polling.

“The multitude and magnitude of issues poll workers are going to have to deal with in this election are unprecedented,” said Aaron Ockerman, executive director of the Ohio Association of Election Officials.

Their success in handling those situations could mean the difference between a confidence-inspiring election between Trump and Democratic rival Joe Biden or the turbulence seen during primaries earlier this year when thousands of older poll workers quit amid COVID-19 concerns.

In Wisconsin, a dramatic reduction in polling places caused by a lack of poll workers in April forced voters to risk their health to stand in lines for hours to cast a ballot.

As those problems became apparent, election officials and activist groups including the student-run Poll Hero Project and Power the Polls – a coalition of voting rights, civic and corporate organizations – began seeking volunteers to step into the breach.

The new recruits are far younger than usual. Of the more than 920,000 poll workers nationwide in the 2016 election, more than 56% of them were above the age of 60, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

By contrast, nearly 90% of the more than 650,000 poll workers that have been referred to local officials this year by Power the Polls are under the age of 65, said co-founder Robert Brandon. The Poll Hero Project has recruited more than 31,000 students, more than half of them high school students, said co-founder Ella Gantman, 19, a student at Princeton University.

‘MY WAY OF VOTING’

Election officials said the widespread interest in working the polls has been encouraging and challenging.

In Michigan’s rural Isabella County, Clerk Minde Lux said she hired and trained her poll workforce months ago, but her office is still being inundated with calls from prospective poll workers through a recruitment program run by the secretary of state’s office. She said she has no more time or money to train additional volunteers.

“We’re just trying to keep our heads above the water, but then people get mad at us, like, ‘Oh, you don’t want us to work the polls,'” she said.

Jacob Major, 17, is one of the new faces who will work the polls in his Milwaukee neighborhood. Major, who now leads the Poll Hero Project’s Wisconsin campaign, said many of the recent recruits are vulnerable to last-minute cancellations because young people have less control over their lives. He also is anxious that the city has not yet told him when his training will take place.

Too young to cast a ballot himself, Major said nothing will keep him from showing up on Election Day.

“Being a poll worker and helping so many young people to sign up as poll workers is my way of voting,” he said.

In Milwaukee, where the decision to cut the number of polling places from 180 to five in the primary because of lack of poll workers led to disarray, the number of polling places on Nov. 3 will be back up to at least 173, said Jonatan Zuniga, deputy director of the Milwaukee City Election Commission.

Zuniga said nearly 2,600 new poll workers had signed up for training and another 1,000 veteran workers would return, resulting in a big increase over the 2,653 poll workers the city had in 2016, according to data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

Yet with COVID-19 cases rising in Wisconsin, Zuniga said he planned to create a pool of 200 standby workers who would be dispatched on Nov. 3 if others do not show up.

“We’ll be monitoring that and see how many back out,” he said. “But right now we’re in good shape.”

(Reporting by Julia Harte and John Whitesides; Additional reporting by Chris Kahn; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Daniel Wallis)