If you’re an American, you’ve probably seen a Zhang Yimou film without realizing it. Back in 2002, the Chinese filmmaker had a crossover hit with “Hero,” his martial arts wonder with Jet Li, Maggie Cheung, Tony Leung and Donnie Yen. You likely saw his handiwork on a smaller screen: He created the phantasmagoric opener to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Zhang makes the types of films — grand, beautiful, populist — that pique Hollywood interest. Traditionally, they’d lure him away from his homeland, as they did John Woo, assign him to some blockbuster. But Zhang found a third way. His first Hollywood film is only half a Hollywood film. It’s “The Great Wall,” a co-production between the big American and Chinese film industries. Hollywood provided a producer, screenwriters and star Matt Damon; China provided everything else, including Zhang at the helm. It’s the first big movie of its kind, and almost certainly not the last. If Zhang was ever going to work in Hollywood, he tells us, this was the only way.

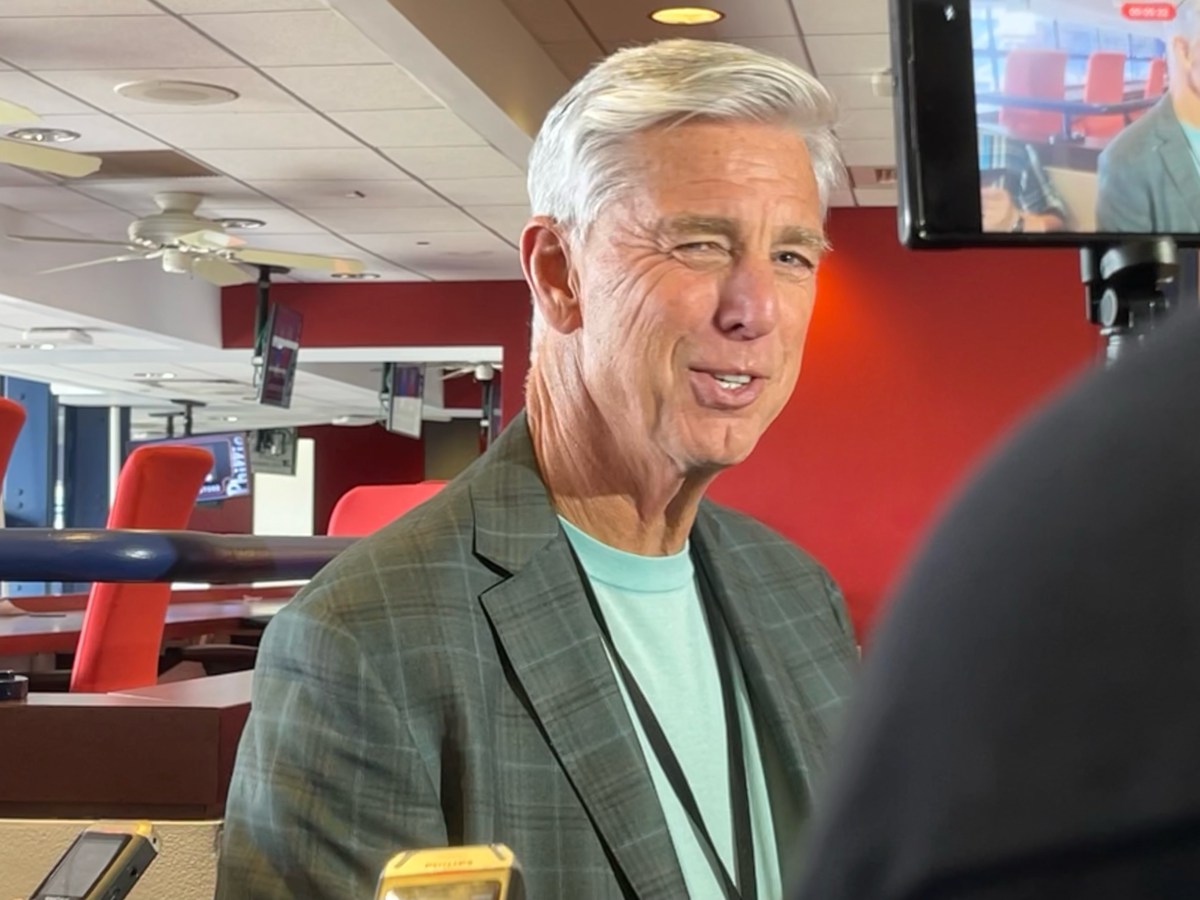

“I’ve always been a Chinese filmmaker making movies in China,” he says. “I’ve always waited for an opportunity to do something like ‘The Great Wall’ — a collaborative production.” RELATED: Review: Turns out the Matt Damon Chinese movie “The Great Wall” is a big monster movie The advertisements make “The Great Wall” look like something it’s not: a historical epic with Damon stomping about Ancient China. Early responses — and, mind you, just to the ads — became an outrage magnet, drawing charges of “white-washing” and that Damon was yet another “white savior,” like Tom Cruise in “The Last Samurai.” The actual film, though, is nothing of the sort: It’s a team effort, with Damon’s globetrotting ex-soldier absorbing himself into another culture, two nations coming together as one, just like the production itself. It’s also a monster movie. “This was the first time in my career I’ve made a movie my children love,” says Zhang, chuckling.

Indeed, “The Great Wall” — which finds China’s mighty, color-coded armies defending their border from an onslaught of green reptiles from space, kind of like an 11th-century “Starship Troopers” — may seem like a super-sized version of Zhang’s martial arts movies, like “House of Flying Daggers” and “Curse of the Golden Flower.” But it’s worlds away from the gorgeous period dramas with which he made his name, like 1987’s “Red Sorghum” and 1991’s “Raise the Red Lantern.” Zhang shifted to bigger crowd-pleasers starting with “Hero,” though he still tries to return to his roots every film or so. Those have become more spaced out over the years. Like Hollywood, the Chinese film industry has gone blockbuster crazy. It, too, used to have diversity, mixing dramas with spectacles. The government even used to impose a strict limit on how many Hollywood films could be released there every year, to ensure Chinese audiences still mostly received Chinese films. That’s loosened over the years, and audiences have developed a taste for Hollywood fare. At this point, Hollywood makes more money in China than in America. When you see a Chinese actor randomly given a small but key role in a Hollywood film — or something bigger, like Donnie Yen and Jiang Wen in “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” — that’s because Hollywood knows their new, global audiences. Meanwhile, China has changed their own industry, creating their own Hollywood-style blockbusters. Last year’s f/x-heavy comedy “The Mermaid” grossed $275 million in its first week alone. (Americans have not returned the favor; “The Mermaid” was quietly dumped in a smattering of domestic theaters.) “The younger audiences in China definitely like more commercial-oriented films,” Zhang explains. “It’s kind of sad to see the change in the market. There’s no longer a demand for art house films. They don’t do as well. It’s hard to get investments for them. I do miss the old times when those kinds of movies were looking highly upon and sought after.” Still, art house films aren’t dead, at least for someone like Zhang. “Don’t worry, I’ll be able to make those,” he says. “But it’s hard to find a good script, that works well with the modern audience and still has the good quality of an art house film.” That said, soon as he’s done with “The Great Wall” press, he’s off to make his next film: a small, intimate drama. All this being said, Zhang doesn’t see much of a difference, artistically, between going small and going big. “The Great Wall” has Zhang’s trademark visual beauty, kineticism and wit, even weird flourishes, like a tower whose colored windows make it look our heroes have entered a rainbow. Even with a $150 million price-tag and two national film industries working together, Zhang was able to stay Zhang. When asked about maintaining his style in the face of a $150 million production with countless moving parts, Zhang chuckles and says, “I tried my best! I tried my best to make it my movie!” The real punchline, though, is that he succeeded.

Zhang Yimou on ‘The Great Wall’ and still trying to make smaller movies

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge.