Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke said if the government caves to leftist demands and has Confederate monuments removed it could lead to a “slippery slope” where next Native Americans will be calling for the removal of statues commemorating leaders who lead violence against their ancestors.

“Where do you start and where do you stop?” Zinke asked in an interview with conservative Breitbart News on Sunday. “it’s a slippery slope. If you’re a native Indian, I can tell you, you’re not very happy about the history of General Sherman or perhaps President Grant.”

Zinke’s rhetoric falls in line with that of conservative commentators and President Donald Trump himself.

“You really do have to ask yourself, where does it stop?” Trump asked as he addressed the Charlottesville protest in which white supremacist groups were protesting the removal of a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Zinke said removing monuments is equivalent to erasing history and vowed the Department of Interior would not remove any Confederate monuments.

“I think we should never hide from our history or erase our history. I think we should embrace the history and understand the faults and learn from it. But when you try to erase history, what happens is you also erase how it happened and why it happened and the ability to learn from it,” Zinke told Breitbart.

But critics are calling bull on what they said is a simplistic response from Zinke that kind of just misses the point.

New Yorker writer Eric Levitz said two easy questions could help Zinke figure out which monuments should stay standing:

1) Is the individual in question historically noteworthy primarily for their service to an evil cause?

2) Was the monument in question erected with the explicit intention of celebrating that evil cause?

In considering the questions, Heidi Beirich, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, told HuffPost it’s pretty easy to know where Confederate monuments belong.

“The proper place for this history is in a museum,” she said.

William Sherman was a Civil War general best known for helping to preserve the union and end slavery in America, but later he participated in the slaughter of Native Americans. During the war, Ulysses S. Grant was also hailed as a great union general, but he also presided over numerous atrocities to the Plains Indians.

Robert E. Lee, on the other hand, is known for leading the Confederate army in their fight against the United States for the right to enslave people.

History of Confederate statues and monuments

What Zinke’s reasoning also fails to acknowledge is that most Confederate monuments were erected decades after the Civil War — typically during particularly contentious times for race and segregation in the United States.

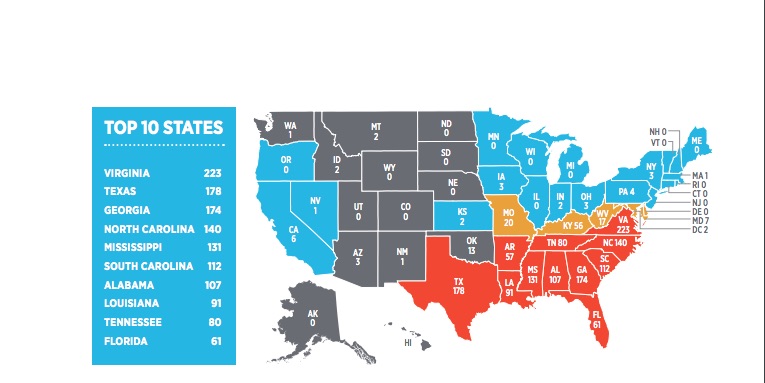

A South Poverty Law Center study found 718 Confederate monuments and statues in public spaces throughout the country, all but three are in the South — two are in Arizona and one is in Massachusetts. When considering all the schools, infrastructure and flags that serve as Confederate symbols, the number reaches past 1,500 nationwide.

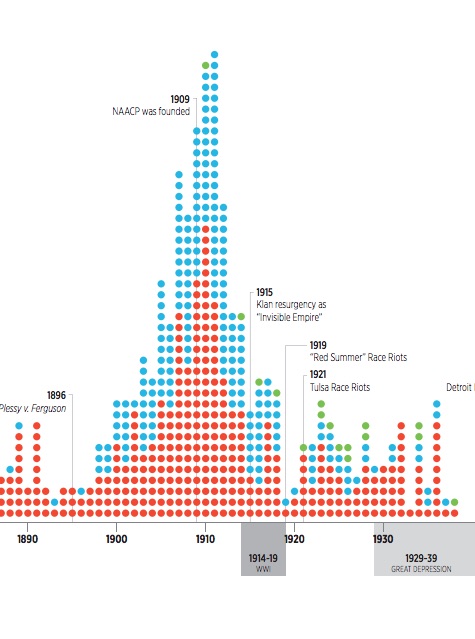

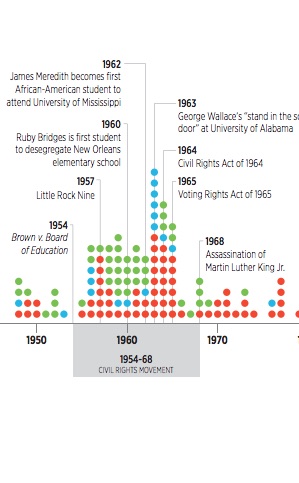

Of those Confederate symbols, the vast majority were erected at the turn of the 20th century — a time when Jim Crow was becoming the law of the land in the South with the goal of segregating newly freed blacks from white society — and around the time of the civil rights movement as a backlash to the end of segregation in America.

Here’s what a timeline of construction of Confederate monuments looks like from the end of the Civil War to present day.

This graphic (via @emayfarris) shows how late most Confederate monuments were put up.

Again, note the timing: Jim Crow & civil rights era. pic.twitter.com/ceDhXxdOD5

— Kevin M. Kruse (@KevinMKruse) August 15, 2017

“Americans of all races, ethnicities and creeds are asking why governmental bodies in a democracy based on the promise of equality should display symbols so closely associated with the bondage and oppression of African Americans,” the report states.

The meaning of symbols like the Confederate battle flag have been tied to themes of slavery and inequality for decades, here’s what the editor of the Augusta Courier paper in Georgia had to say about its gaining notoriety in 1951.

“It means the southern cause. It means the heart throbs of the people of the South. It is becoming to be the symbol of the white race and the cause of the white people. The Confederate flag means segregation,” Roy V. Harris said.